This post originally appeared as part of my column “Brain Hacks for Writers” on the now-dormant online magazine Futurismic.

Do writers who use critique groups do better than writers who don’t? Do writers need mentors? What differentiates a bad writer from a good writer, and a good writer from a great writer? Does it always take time to develop writing skills, or do some people just have them right off?

All complicated questions. Here are some answers.

Born with it?

The first thing I have to tell you may not go down easily if you haven’t come across it already. This is it: you were born with pretty much no talent for writing. The same with me. Also Stephen King, William Shakespeare, and the screenwriter forDude, Where’s My Car? … well, let’s not look too closely at that last example. The point is, virtually all writing skill islearned.

I can understand if this isn’t easily believable. The myth of talent is rampant in our culture: the standard idea is that any time we see someone who can do something really well, it’s because that person is just naturally gifted in that area. It’s an understandable mistake to assume that, but other than in very limited ways, like physical build for some kinds of athletes and range of intelligence for many fields, genetics does not determine what a person will be good at.

What does? Practice: lots and lots of focused practice, with lots and lots of feedback. Toddler Mozart practicing music for hours and hours every day under the watchful eye of one of the most celebrated music teachers in Europe at the time–his father. Tiger Woods got long, intensive golf lessons at a very young age from a highly accomplished golf teacher–hisfather. And so on.

Practice and feedback

I won’t work too hard to convince you of the importance of quality practice here, but if you’re interested (or absolutely disbelieving), try my post Do You Have Enough Talent to Be Great at It?, or read Geoff Colvin’s extensively-researched book Talent Is Overrated or the first part of Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers. Skill and artistry come from deliberate practice, which is to say practice that is undertaken in a smart way, that presents challenges, and that gets constant feedback.

Getting deliberate practice means pushing ourselves. Just showing up and putting in minimal effort doesn’t get us anywhere, which is why a mediocre accountant can keep books for 40 years and retire not much less mediocre than he started, if he doesn’t actively try to get better with challenges and feedback.

The feedback part is especially crucial. The process of improving our skills in a particular area is essentially one of try-get feedback-incorporate feedback-try again. If we don’t get feedback, then we have no useful information to apply to our next try, and we’re not likely to get any better.

Ways to get feedback

Fortunately, sources of feedback for writers abound. First of all, our own reactions to our writing are feedback, and while that feedback isn’t unbiased, it can be useful. For instance, if I write a story and am excited by what I’m writing–whether it’s coming out easily or has to be dragged word by word from the gaping pit of Hell–then that bodes much better for the work than if I have no strong reaction to it, or only have vague hopes that it might be good enough.

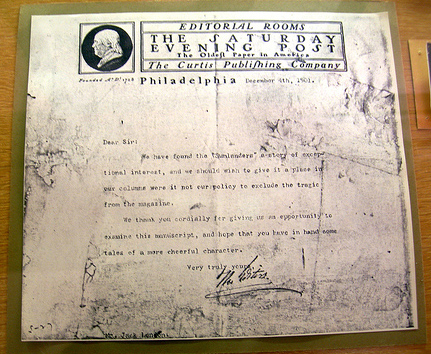

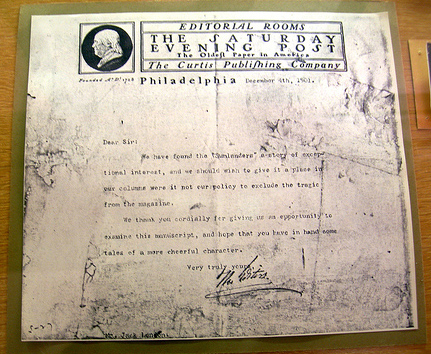

But feedback from others is even more valuable, because other people will react more to the story on paper than to the story the writer is imagining. Every story critique we receive, every family member who sits through reading something we’ve written or starts to read it and then makes an excuse to put it aside, every rejection letter, every personal note scrawled in the margin of a rejection letter, every acceptance and rewrite request, every review, every letter from a reader who loves or hates the story helps tell us how we’ve affected one particular reader–and in the case of editors and agents, that reader’s professional opinion of the impact of our writing will likely have on other readers.

The problems are that every reader is different and that some of the feedback we get isn’t even a faithful representation of what the reader really thinks. A writer I know, for instance, went through a critique group where she was energetically encouraged to submit a book–a book that it later turned out most of the encouraging parties hadn’t even read. Then she switched into a critique group where one particular member seemed to be certain that she had no idea how to tell a decent story, on the theory that his opinion alone was valid to tell what was and wasn’t decent writing. (More on these particular incidents can be found in my article Telling Bad Advice from Good Advice.)

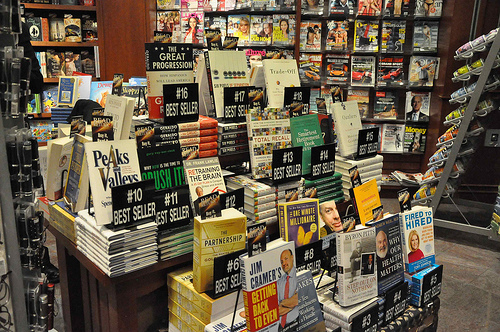

Still, it’s essential to get some kind of outside feedback on writing, even if that feedback is only rejection slips, acceptances, or sales figures–with more feedback being better as long as the writer can keep up with it. But it’s also essential to realize that no single person can give complete feedback on any piece of writing. A person can only pass along an individual reaction and, if that person is an experienced professional in writing or publishing, conclusions based on professional experience–which can also easily be off. For instance, J.K. Rowling’s agent had to spend a full year finding a publisher for the first Harry Potter book because publisher after publisher kept rejecting it: their experience told them it was too long to sell. They were right, in a way: the recent successes for that age group were much shorter books (although it’s hard to say if that was in part self-fulfilling, that no one would publish longer books due to the conventional wisdom that longer books wouldn’t sell). Like everyone, these publishers have individual tastes and limits to their knowledge. No one opinion can be comprehensive.

Yoda, Gandalf, Donald Trump

Which brings us to mentors, who can be incredibly helpful or the worst possible influence. After all, if a mentor has very high credibility then we tend to put a lot of weight on whatever they say, whether they’re saying that your story is great and should sell to a major market (Orson Scott Card, speaking to a writing student whose story sold immediately on being sent out) or San Francisco Examiner editor who reputedly rejected Rudyard Kipling with the words “I’m sorry, Mr. Kipling, but you just don’t know how to use the English language.” If the mentor has low credibility, then we tend to disregard what they’re saying unless it completely agrees with our own already-formed opinions, but a high-credibility mentor can create beliefs about our work that may or may not be any help to us going forward. One writer I knew wrote a piece of flash fiction that was praised highly by a seasoned pro. The writer, preoccupied with the high praise, rewrote the piece over and over for years as it grew into first a short story, then a novelette, and then a novella. To the best of my knowledge, he never did sell the final version.

The worst mentors, though, are those with high credibility but little real experience. For instance, while some college writing professors are excellent mentors, others may have no successful experience of their own in the kinds of writing that interest you. For instance, if you want to write historical romance novels, what’s the value of feedback from a professor who doesn’t read romance and whose own publications are limited to intensely experimental fiction published in tiny literary magazines? We won’t even talk about a writing teacher whose work hasn’t been published anywhere significant at all.

But if we imagine for a minute a mentor who has good credibility and whose comments tend to offer a lot of insight that the student doesn’t already have, it quickly becomes apparent how useful one can be. Someone who really knows what they’re talking about can set the record straight very quickly and accelerate the process of becoming a better writer. At “Uncle Orson’s Literary Boot Camp” in 2001, Orson Scott Card talked to me and the 19 other participants about actively coming up with ideas instead of waiting for inspiration to strike, and then had us use different strategies to come up with those ideas until we saw that we could conjure them on demand. At the Writers of the Future Workshop in 2003, Tim Powers talked about the importance of using the senses in writing (for example, he recommended knowing where the light was coming from in every scene), and that good advice has stuck with me, too.

Fortunately, mentors also come in convenient book and blog form. Books like Donald Maass’s Writing the Breakout Novel, Noah Lukeman’s The First Five Pages, Orson Scott Card’s Characters and Viewpoint, or Stephen King’s On Writing (other suggestions in comments are welcome) deliver an enormous amount of useful information that can prevent having to learn their lessons through years of trial and error, or worse, never learning those lessons at all. But this isn’t feedback per se, just ideas that we can incorporate into our own attempts. Feedback from ourselves and others will eventually tell us how successful those ideas were.

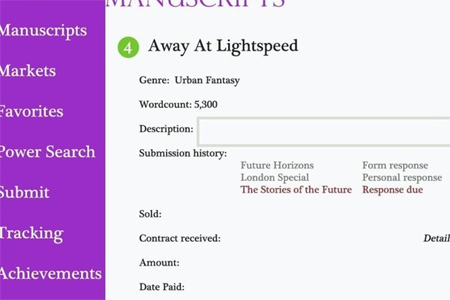

The real magic starts happening once we write and send our work out into the world–to a friend, to a critique group, to a magazine, to an agent, to a mentor, or anywhere where it can be praised, scoffed at, devoured, or ignored. Card theorized that writers have a million words of garbage to write before their writing gets consistently good, and this might be a pretty good rule of thumb–something along the lines of Malcolm Gladwell’s assertion (which he does a good job of backing up with evidence) that regardless of the skill, it takes about 10,000 hours to become really world class (not just professionally competent) at something. In both cases, the pages and hours are practice, and practice is more effective when it’s more challenging and when it includes more and better feedback–so that the length of time and the amount of work between where we are now and where we want to be as writers becomes shorter the better the quality of our practice and feedback.

Photo by /Sizemore/

Like this:

Like Loading...

In Star Wars: Episode I, Qui-Gon Jinn quips “There’s always a bigger fish.” Admittedly he’s wrong, because since there aren’t an infinite number of fish in the universe, so one fish or group of fish has to be the biggest. And I’m probably wrong too when I say “there’s always another way to write it”–but as with the fish thing, it appears that it’s a rule that’s always accurate.

In Star Wars: Episode I, Qui-Gon Jinn quips “There’s always a bigger fish.” Admittedly he’s wrong, because since there aren’t an infinite number of fish in the universe, so one fish or group of fish has to be the biggest. And I’m probably wrong too when I say “there’s always another way to write it”–but as with the fish thing, it appears that it’s a rule that’s always accurate.