Like it or not, many of our decisions, actions, and opinions happen based on an instant response, without any careful thought. For example, we may see someone we don’t like and grimace for a microsecond before putting a more polite expression on our faces; miss momentary opportunities through being mired in depression or anger; or misjudge a person by their face or clothing.

Like it or not, many of our decisions, actions, and opinions happen based on an instant response, without any careful thought. For example, we may see someone we don’t like and grimace for a microsecond before putting a more polite expression on our faces; miss momentary opportunities through being mired in depression or anger; or misjudge a person by their face or clothing.

These instant responses are the subject of Malcolm Gladwell’s book Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking. They’re also a part of our behavior that is extremely hard to change. For example, the vast majority of people of all races to take a test to judge racial bias based on how easily they sort faces into categories like “good” or “criminal” come out with at least a mild bias against blacks even when they are consciously and emphatically in support of racial equality. Even knowing this, and knowing how the test works, people taking the test are unable to overcome a bias that may have been ingrained, unfortunately, through hundreds or thousands of cultural channels.

But there is one way to change things for some test takers: thinking about admirable black people, current or historical, tends to cause test-takers’ racial bias to disappear. Thinking about Martin Luther King begins to put all black people into a positive light.

This effect isn’t limited to racial bias. Some other examples of priming experiments:

- People who answered trivial pursuit questions after thinking about what it would be like to be a college professor did 13% better than people who were asked to think about traditionally non-brainy subjects–that’s the equivalent of getting more than a full grade better on a test, just from a few minutes of mental preparation!

- Being unknowingly exposed to a number of words that described age tended to make subjects in one study walk more slowly.

- People primed with ideas about patience would wait for any length of time for people to finish a conversation instead of butting in.

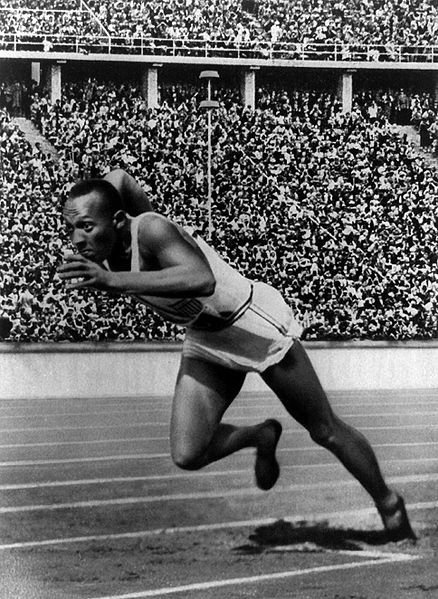

The power of priming, then, is in being able to change our unconscious, immediate, ingrained reactions. If these studies mean what they seem to imply, then if you’re going to a party hoping to make a romantic connection, you’ll be at an advantage if you spend time thinking about romantically successful people. If you’re afraid your future in-laws from rural Appalachia won’t like you, listen to some champion fiddlers and avoid watching reruns of The Beverly Hillbillies. If you’re going to run a race, try reading something about Jesse Owens first.

The power of priming may not be dramatic, but it’s significant, and priming affects the knee-jerk responses we usually can’t do anything about.