This is the final post in a series interviewing 3rd degree black belt Aikido practitioner Dwight Sora of Chicago Aikido club. While I’m interested in martial arts for their own sake, Aikido strikes me as having some unusual philosophical lessons about acceptance, change, and growth.

Previous posts in this series are Aikido Interviews, #1: Trying to Discover Truths, Aikido Interviews, #2: “Lift Your Head and Say ‘Isn’t Today a Great Day?’”, Aikido Interviews, #3: Like Learning How to Play Music, and Aikido Interviews #4: Something Had Been Activated.

Luc: What, in your mind, are the greatest insights aikido can help teach to the world?

Dwight:

I think the best thing about aikido is that it offers a different way of looking at conflict: the idea that there is a positive and active middle ground between a purely aggressive forward-moving approach to solving a problem and being passive and surrendering. Now, accepting that as a life lesson assumes that you are willing to believe that the physical element of aikido truly possesses a social or perhaps psychological equivalent in the real world. Though, that’s okay with me, because aikido does not really “work” unless you are willing to believe in it conceptually in the first place.

Now, I’m not saying that I think an aikido approach to life is better or superior than any other. Would have an aikido-type strategy have worked for the Allies in their fight against the Axis? Would Gandhi have made faster progress if he approached things with aikido in mind in dealing with British colonialism as opposed to pure passive resistance (and I honestly don’t know what form that would have taken)? Who can say? That’s not what happened and not the approach that folks used to win.

I’ve also heard stories about some aikido instructors who have found themselves in actual fights (attempted muggings, street brawls, bar altercations, etc.). And in each of those stories (which might be apocryphal) the results certainly didn’t seem in the spirit of aikido’s philosophy. One story I heard basically involved the instructor punching a guy in the face and breaking his nose. I see a couple of questions in that story. Was his ability to deliver that punch a product of his aikido training or simply because he knew how to fight on a fundamental level unrelated to aikido? Is this actually a story of aikido failing, since he didn’t really do any of the techniques we practice regularly? Does this story diminish the significance of aikido since someone so accomplished in the art seemed not to demonstrate the supposedly peaceful philosophy espoused?

I have met more than a few students of aikido, and some instructors, who say they think all the philosophical stuff is B.S. That the only thing that matters in the study of martial arts is if it is real.

My personal take: Aikido represents an ideal. Its philosophy, its techniques and its approach represent a possible outcome to situations of conflict if we are willing to accept them. And by ideal, I mean something that we should all strive to accomplish, but that does not mean it is something we must accomplish or even can accomplish (depending on the person or situation). If you start doing some serious comparison and analysis, very little of aikido’s techniques are unique to aikido on a technical level. You can find stuff in common with judo, jujitsu, Chinese chin-na grappling arts and other things. The human body can only be manipulated in so many ways.

Put simply, aikido is an attitude. That’s why we have all the bowing and ceremony, a specific dress code and remove our shoes and socks. None of those elements have anything to do with practical fighting. If that was the case, we’d be training on concrete or open ground in our street clothes. It’s an act of shedding our regular outward affectations in hopes that it helps us dump our egos and opens our mind up to new experiences.

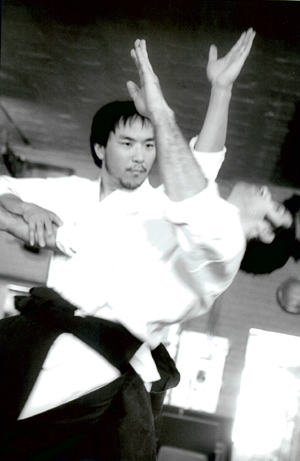

Photo by Maggie Mui

Luc: What’s the relationship between engaging with the world and engaging with an attacker? What approach or approaches does Aikido indicate for a practitioner who is being attacked?

Luc: What’s the relationship between engaging with the world and engaging with an attacker? What approach or approaches does Aikido indicate for a practitioner who is being attacked?