As a rule, our culture tends to think of emotions as things that well up inside us in a way that’s more or less completely outside our control. We can avoid emotional situations, this point of view goes, or we can suppress them, but they are what we are, and thinking doesn’t enter into it.

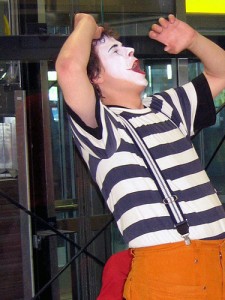

I’d like to demonstrate some very useful ways this is completely wrong. I’ll do it using, of course, a mime.

I’d like to demonstrate some very useful ways this is completely wrong. I’ll do it using, of course, a mime.

Let’s say our mime–for convenience, we can call him Raoul–is on his way to the park to do a little street performance on a sunny May afternoon. For his performance today, Raoul has purchased three dozen imaginary eggs, which he plans to juggle, balance on his nose, perform magic tricks with, etc. He is carrying the imaginary eggs in mime fashion when he slips on an imaginary banana peel on the sidewalk and crashes to the concrete, right on top of his eggs. Now Raoul is a mess, covered with imaginary egg. All of his eggs are ruined, so there go his performance plans for the day, and to top it off, the people in his otherwise fair city are so rude and thoughtless that they leave imaginary banana peels lying all over the place. Oh, and to make it worse, since it was an imaginary banana peel, clearly it was another mime who did it!

We would expect Raoul to get upset in one way or another. He could sit there, covered with smashed eggs, weeping, or he could fling the gooey, imaginary cartons around in fury, shouting silent curse words. And we probably wouldn’t blame him for this, because through someone else’s carelessness, he’s a mess and his day is ruined.

Now, it’s true that immediately when this happens, Raoul’s brain will start making associations, and brain chemicals will start influencing his behavior–notably adrenaline in response to the unexpected fall and the problems that it has suddenly caused. That helps set the stage, but at the same time Raoul’s brain is likely to be generating what are called “automatic thoughts”: emotionally laden and potentially misleading judgments about what has happened. They might include things like:

“I’m screwed! I needed those eggs for this performance, and if I don’t perform I won’t have enough money to pay the rent tomorrow, and then I’ll probably get kicked out of my apartment!”

“What kind of sick #$!(@ leaves imaginary banana peels lying around all over the sidewalk?”

“This is a disaster!”

These kinds of automatic thoughts are also called “cognitive distortions,” because they are a kind of thinking that encourages belief in things that aren’t true. I’ll use a different term for them, though: “broken ideas.” A broken idea is anything you think up that misleads you. But what’s misleading about the above? Isn’t Raoul just silently telling it like it is?

In all honesty, he isn’t. Raoul’s broken ideas are broken only subtly, but they’ll lead him down a path he doesn’t want to take. For instance, his predictions about being evicted are very likely wrong, even if he isn’t able to come up with every penny of the rent money on time, and the fact that he’s trying to predict the future rather than just evaluate his options is a major red flag. We can’t predict the future in most cases, so basing our actions on assumptions about what will happen tends to lead to badly-chosen actions. Anyway, even in the worst case scenario he can always show how he’s trapped in a box and unable to leave the apartment. This is one of the powers mimes have.

He’s also telling himself he needs the eggs for the performance, when in fact he probably just wants the eggs for the performance, and can either buy more eggs or do a different routine.

And he’s also labeling the banana peel leaver as a (please pardon me for repeating this bad language) “sick #$!(@,” which dehumanizes the person and could lead some real interpersonal problems (like being hit over the head repeatedly with an imaginary stick) if Raoul decides the perpetrator must have been a particular someone he knows and acts toward that person as though they were purposely going around and leaving imaginary banana peels for people to slip on.

So what’s wrong with these ideas is that they’re inaccurate, and more to the point, they tend to lead Raoul in the direction of making bad choices, like going to drown his sorrows in imaginary beer, or marching off to throttle a colleague who is a known banana afficianado. What would make Raoul happiest at the moment would be to somehow find a way to free himself of his anxiety and frustration at the incident, get him to think through what he’ll need to do to go ahead with his performance, and as soon as possible to get him to the park to charm half the passersby and infuriate the other half with his mimetic ways. This way his day could very rapidly get back on track, and no other trouble would need to come of the banana peel fiasco.

How does Raoul do this? We’ll tackle this in much better detail in other posts, but the basic steps are:

1. Relax, step back from the situation, and breathe

2. Use idea repair

3. Get on with your life

Idea repair, which takes some practice to learn but can be wonderfully effective once you have the basics down, is the process of reworking broken ideas to reflect the truth of the situation. For instance, “What kind of sick #$!(@ leaves imaginary banana peels lying around all over the sidewalk?” could be repaired to something like “As much as I wish they didn’t, sometimes people will leave imaginary banana peels on the sidewalk, so I’ll be better off if I’m on the lookout for them.”

Similarly, “This is a disaster!” could be repaired to “This is inconvenient and embarrassing, but if I take the right steps, I can get my day back on track.”

You might be amazed how much stress and distraction idea repair can sometimes clear away. I certainly have been ever since I first learned about the technique a decade or so ago.

Of course there’s much more that could be said on the subject, but that brief summation will have to do for now. I’ll leave you with this final comment from Raoul:

“”

Huh. Well, that’s what I get for trying to quote a mime.

Mime photo by thecnote; banana peel photo by Black Glenn.

Postscript: As you may have noticed, I’m experimenting with a lighter writing style for posts. Up until now I’ve been making efforts to write seriously because I’m dealing with serious subjects, but I’ve come to think that a little humor might do more good than harm. I’d appreciate any comments you might have on this style of post.

LATER NOTE: I followed this article up in October with How to Detect Broken Ideas and How to Repair a Broken Idea, Step by Step.