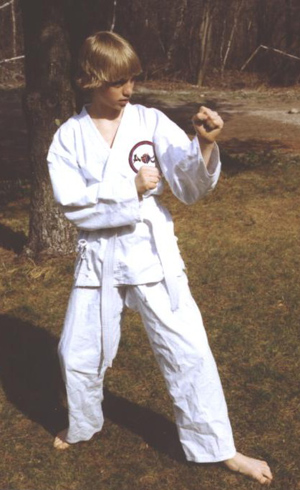

Gordon White holds a 6th dan black belt in Taekwondo Chung Do Kwan, a rank that takes upward of 20 years of hard practice and constant study to attain. He has sparred and won medals both nationally and–as a member of the U.S. national team–internationally, teaches Taekwondo on his own time four or more days a week, and serves as President of the Blue Wave Taekwondo Association, a New England group with hundreds of members.

It’s through Blue Wave that I know Master White: I’m in training to test for my 1st dan black belt in March of 2010. Having long been struck by Master White’s passion for Taekwondo as well as by his drive to teach, I asked to interview him for The Willpower Engine. When he agreed, I received some unexpected and enlightening answers to my questions.

Following is part I of excerpts from the interview in Master White’s own words (except for the headings I’ve added), with part II available here. To read the full interview, unedited, click here.

It started with bullies

It started with bullies

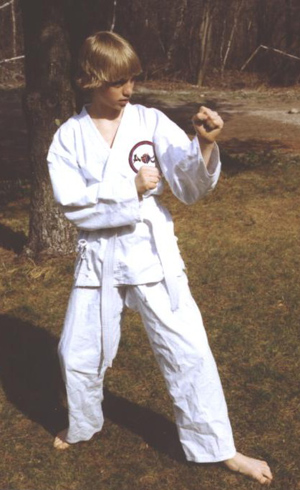

I started Taekwondo May 13th, 1983. I was in the eighth grade. The 6th and 7th grades were tough on me: I was picked on and beat up a lot, and now was nervous about being a freshman in high school the following year. My older sister had a boyfriend who practiced Taekwondo, and he invited me to visit his school.

So my parents brought me over on Friday night. We talked to the instructor, who had me fill out a form. There was a list of about 20 different “benefits” of Taekwondo training. Self confidence, physical fitness, self defense, competition, etc. I checked off all but 1 or 2….(I think weight control was one that I left off). I signed up that night, and was hooked. For the next 2-1/2 years, my parents drove me to Winooski 3 to 5 times a week. While I had other interests (drumming, skiing, BMX biking …) which I continued to be involved in through High School, they quickly became a second priority to Taekwondo.

Self defense is what motivated me to walk in the door of a Taekwondo school, but what kept me there were number of things. I was good at it, but I also felt like belonged there. I was surrounded by 5 men in their twenties who were black belts, and in my eyes were like having 5 Bruce Lee’s to practice with. I wanted their physical skills, strength, and confidence, and my instructor made me feel like I was capable of achieving it. I was made to feel that I had tremendous potential, and that by practicing Taekwondo and dedicating myself to it, I would be successful in anything I wanted to pursue. While my motivations and goals changed–instructing, competing, etc.–I guess once I started Taekwondo, NOT doing it was never an option.

Parents’ and instructors’ expectations

Part of my motivation was driven by my desire to to live up to someone else’s expectations. My parents, instructor, and coaches all played a very important role in me staying motivated and dedicated to continue with Taekwondo. Those that come before you have the experience to know what is possible–so they set high expectations for you, higher then perhaps you can imagine on your own. It’s fantastic, because it helps you do more than you would most likely accomplish otherwise. However, with it comes pressure. I see parents all the time who don’t think they are putting pressure on their kids, coaches who have a “low pressure” philosophy, but as long as there are caring instructors there will be pressure on the students.

From the time I started Taekwondo and got my yellow belt [an early beginning rank], I intended to be a Taekwondo instructor. I was fortunate to find the Blue Wave and Master Twing–but if I had not, I don’t think it would have stopped me. I think I would have continued to search until I found an instructor that I could connect well with.

The pressure to perform vs. enjoying a thing for its own sake

Luc, in reading Keyna’s favorite movie list, I was reminded of one of my all time favorite movies Searching for Bobby Fisher. The main character, Josh Waitzkin, (this is based on a true story) has supportive parents and coaches, [who all] see his potential (he’s considered a gifted chess player) and are driven to support and push him, thus creating tremendous pressure for him. The conflict he feels between wanting to just enjoy chess and excel to the point that he thinks his coaches/parents want is very well portrayed in the film.

By the time I was in college, my desire to do well in Taekwondo was driven almost entirely by my own motivation. I think the trick with motivation is that if it’s a chore, it’s not really motivation: real motivation has to come from within. External influences can help, but I think this can turn into a feeling of responsibilty, or a fear of disapproval. No one was telling me to get up early to run–or give up social events on Friday night because I was traveling to a training session or tournament. I did these things on my own, because I wanted to. It never felt like a sacrifice for me.

Essex, Vermont Blue Wave Taekwondo members, 1989

College as a goal–and as an obstacle

College got in the way of Taekwondo … My first two years of college were done out of responsibility–not motivation. All I wanted to do was Taekwondo: studying was not high on my list, but my feeling of responsibilty to my parents to “get a four year degree” had me putting in minimum effort to get by. It was a bumpy road – 6 years for a four year degree including some time off and a year abroad, but in the end, Taekwondo is what provided the real motivation for me to finish school. I FINALLY claimed a major, “small business management,” which allowed me to link what I was learning, to what I eventually saw myself doing, owning a Taekwondo School.

Another obstacle for me was the lack of training partners and travel distances. When I started Taekwondo in 1983, I was able to train 4 or 5 days a week. But in 1986, I began training with Master Twing in Randolph, Vermont, a 100-mile round trip. I was only getting down 1 or 2 times a week–when Grandmaster Lee arrived in late 1987 and came back again in 1988, I would often spend weekends at Master Twing’s house, training with Grandmaster Lee in the basement.

A montage of board breaks and sparring by Gordon White from 1987-1990

The missing ingredient

By 1990, I had failed to place at Nationals after 3 attempts, 1987, 1988, 1990. I missed 1989 due to knee surgery–another obstacle, I suppose. I felt like I should be on the podium, but something was missing–the people that were placing had something I didn’t, and it wasn’t physical skill: it was confidence. While I spent all of my training time sparring with people that were not as good as I was, the best players were from big cities, training with teams of national level competitors. This was the difference. The only time I had experienced this was in 1987: Grandmaster Lee took myself and one other black belt to Korea for 6 weeks. We traveled around the country, training at different schools and getting our butts kicked on a regular basis. The dramatic increase in skill and confidence I gained just in these 6 weeks was something I needed much more of.

I headed to the International Education office at UVM and asked what my options were for a year abroad in Korea. I was given information for attending Yonsei University, and started making plans for it. In order to go, I needed to get my grades up at UVM (I did); I needed to close my Taekwondo School (one of my students, Tim Warren, wanted to open a school in Milton, which gave me a place to send my students); I needed to continue to train as hard as I could–I still had nationals to attend and if I hoped to keep up in Korea, I wanted a good foundation–and lastly, I needed to earn as much money as I could, because I would not be working for the year there. I waited tables at the Peking Duck, picking up extra shifts.

Click here to read part II of the interview, following Master White to Korea, back to the U.S., and to the heights of competition.

Photos and video courtesy of Gordon White.

Like this:

Like Loading...

My current reading is

My current reading is

Gordon White at Nationals in 1997

Gordon White at Nationals in 1997

It started with bullies

It started with bullies