The common knowledge about heart health is that fat is the enemy. In recent years we’ve tweaked that idea with the concept of “good fats” in moderation, but basically “low fat” has been the wisdom we’ve heard from doctors, the media, and the government.

Peter Attia is a surgeon with an extensive background in mathematics and statistics who has been intensively researching heart health, weight loss, and many related physiological processes for the last several years. The problem, Attia, says, is that the actual scientific research points in completely the opposite direction: it fingers carbohydrates, especially sugar, as the heart killer, the clogger of arteries and generator of flab. Fat, according to the research he’s talking about, is not just benign–it’s crucial, because we still need a source of energy in our diet, and if we cut out fats and carbohydrates we have nothing left but protein, which isn’t a great source of energy and is comparatively very expensive to boot.

So the idea is to eat enough fat to feel sated and to keep consumption of carbohydrates, especially sugar (and especially especially high-fructose corn-syrup, a.k.a. HFCS) low.

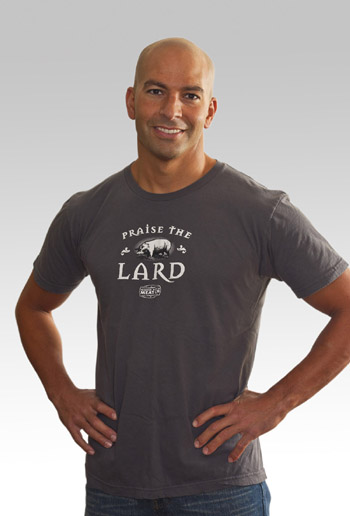

If you find yourself thinking that Attia is some kind of obsessed weirdo with unscientific ideas about fats, I suspect you may change your mind if you read some of the in-depth, highly analytical posts on the subject he has on his Web site, eatingacademy.com. (It’s just an informational site, by the way: he’s not selling anything.) Though come to think of it, it might make the case a little more clearly and effectively if you just take a look at the guy. Does he not look like he understands something about weight loss, heart health, and physiology?

So I encourage you to take a look at his site. If you’re concerned about cholesterol, which was the main thing that got me interested in Attia’s writing, here are a few key points as I understand them:

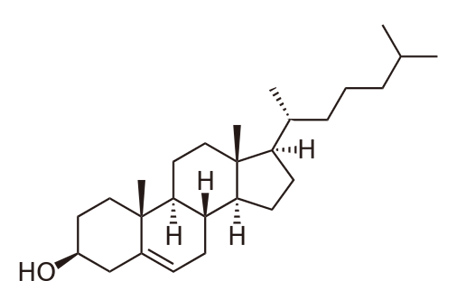

- Cholesterol is an important material our body uses to repair cells, and without it we’d die–yet as we know, it can cause heart attacks, strokes, etc.

- Almost every cell in our body can manufacture cholesterol, and the great majority of cholesterol in our bloodstream is cholesterol our bodies have made.

- Very little of the cholesterol we eat stays in our body: most of it isn’t absorbed. (Attia explains the how and why of this at length.)

- Therefore, the amount of cholesterol we eat doesn’t have much to do with heart health at all.

- By contrast, carbohydrates–especially sugars–tend to cause cholesterol to embed itself in artery walls and build up there, a condition called Atherosclerosis.

- It’s not the total amount of cholesterol in a person’s bloodstream that indicates danger of Atherosclerosis, but rather the number of cholesterol particles, because the particles can be different sizes and carry different amounts of cholesterol, and it’s the smallest ones that are most dangerous.

- The usual “cholesterol test” most of us have been given measures only the total amount of cholesterol and are therefore fairly useless in predicting Atherosclerosis and related conditions.

- Less common tests that measure the number of cholesterol particles in our blood are much better indicators of heart health. (By the way, yes, “good” versus “bad” cholesterol still comes into play.)

Don’t take this from me, because I’m no expert: Attia has a lot more information on it at his site. However, I’m hoping the above conveys the idea well enough for you to decide whether or not you’re interested in hearing more about it on Attia’s site. He’s obsessed with this topic, and for good reason.

I’m not saying, by the way, that I know all this to be true and accurate. However, I’ve found the evidence compelling enough to have shifted from a low-fat diet to a low-carbohydrate (and high-fat) diet over the past couple of months. Since medical tests have revealed I have the beginning of plaque buildup in my arteries, in a way I’m literally betting my life that Attia’s right. If he is, that would explain why greatly limiting my cholesterol intake didn’t seem to help my cholesterol count, and why years of eating just the kind of diet the traditional “wisdom” on the subject dictates led me to the beginnings of Atherosclerosis.

An important, related note: if you do switch to a much lower-carb, higher-fat diet, please, please do so in a way that takes into account your carbon footprint. Red meat, for example, makes a much worse impact on climate change than plant-based foods–unless you’re getting pastured or grass-fed meat, which is close to carbon neutral . It doesn’t matter if you’re as healthy as a horse if ten years from now you and your family are drowned in the latest superstorm, or are starving due to a global famine brought on by changing climate, droughts, floods, and pests. I don’t mean to be a wet blanket here, but it’s important for me to mention it. If you’re interested in becoming part of the solution to climate change rather than the problem, check out the things I’m posting at www.faceclimatechange.com and consider switching to much more local food sources; see www.localsource.me .