Today’s article is a guest post from Former Wall Street Journal and Fortune writer Erik Calonius, whose book Ten Steps Ahead: What Separates Successful Business Visionaries from the Rest of Us you’ll hear more about here in the near future. You might also be interested in reading his post on Jonathan Field’s blog, “What Lucky People Do Different,” which I recommended here about a month back. You can find out more about Erik at his Web site, Calonius.com.

Today’s article is a guest post from Former Wall Street Journal and Fortune writer Erik Calonius, whose book Ten Steps Ahead: What Separates Successful Business Visionaries from the Rest of Us you’ll hear more about here in the near future. You might also be interested in reading his post on Jonathan Field’s blog, “What Lucky People Do Different,” which I recommended here about a month back. You can find out more about Erik at his Web site, Calonius.com.

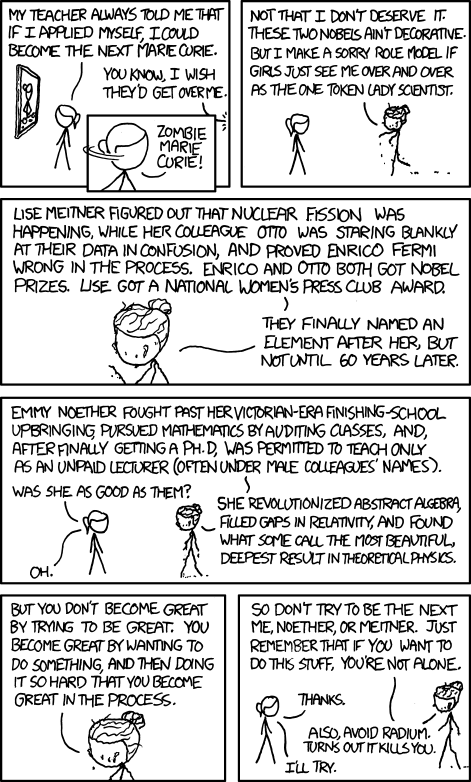

I saw a lot of wisdom in Randall Munroe’s XKCD cartoon strip (May 16 post)—the one where Marie Curie is telling Nobel Prize wanna-bes, “You don’t become great by trying to be great. You become great by wanting to do something, and then doing it so hard that you become great in the process.”

In our instant gratification society, too many people just want to be great. They don’t want to take the long, often-lonely journey to get there. They want to be a movie star, not an actor; an American Idol, not a singer; the next blockbuster novelist (interviewed on Oprah), not a writer.

These frothy ambitions are not restricted to the arts. I recently had dinner with two senior research scientists from Bell Labs. Bell Labs, you may remember, is the research lab that produced the transistor, the laser, the UNIX operating system. Among its many notable scientists, seven of them went on to win Nobel Prizes. So did these senior researchers (that I had lunch with) want to be great, too, with their pictures placed prominently on the walls at Bell Labs? Of course. Who wouldn’t?

People have always wanted to be great (that’s why Alexander wasn’t called Alexander the Mediocre). Truth be told, even Marie Curie wanted to be great. Proof of this: As soon as she discovered radium she reported her findings to the scientific community. She did it the next day. She wanted to be great, too!

People have always wanted to be great (that’s why Alexander wasn’t called Alexander the Mediocre). Truth be told, even Marie Curie wanted to be great. Proof of this: As soon as she discovered radium she reported her findings to the scientific community. She did it the next day. She wanted to be great, too!

Wanting to be great is only human, but it has become a runaway addiction in our modern society. It’s the result of living in a country where there are few ceilings, I suppose, where some people really do go from subsistence to the stratosphere overnight.

So it’s important, as Madame Curie (and cartoonist Randall Munroe) reminds us, “You don’t become great by being great. You become great by wanting to do something. And then doing it so hard that you become great in the process.”

There’s another element to greatness, however. It’s luck. Countless millions of people have worked hard and selflessly at tasks. And yet they have died in obscurity, at least as far as the newspapers and histories are concerned.

Why? Nassim Taleb, in his wonderful book, The Black Swan, explains it well: “The graveyard of failed persons will be full of people who shared the following traits: courage, risk taking, optimism, et cetera, just like the population of millionaires. There may be some differences in skills, but what truly separates the two is for the most part a single factor: luck. Plain luck.”

So where was Madame Curie’s stroke of luck? In her case it was being turned down by the University of Krakow where she was to study magnetism, and meeting her husband Pierre Curie. Her luck continued when Pierre showed her a quirky device called an electrometer. Her husband and his brother had invented it 15 years earlier to measure electric current, and had essentially put away in the closet. Curie pulled it out, and using it, discovered that uranium caused the air around a sample to conduct electricity. No one had done that before.

Now you may say that those are circumstances rather than luck. But in many cases they are one and the same. Orville Wright would not have invented the first workable airplane without Wilbur; Walt Disney would have been penning cartoons in Kansas City if not for his brother Roy, who encourage Walt to come to LA, and then kept Walt from running the business into bankruptcy; Steve Jobs, of course, wouldn’t have been able to start Apple had he not chanced upon Steve Wozniak as a kid.

Now you may say that those are circumstances rather than luck. But in many cases they are one and the same. Orville Wright would not have invented the first workable airplane without Wilbur; Walt Disney would have been penning cartoons in Kansas City if not for his brother Roy, who encourage Walt to come to LA, and then kept Walt from running the business into bankruptcy; Steve Jobs, of course, wouldn’t have been able to start Apple had he not chanced upon Steve Wozniak as a kid.

But luck is more than the creation of dynamic duos. I’ve been working lately on a book about electricity, and what is surprising (dare I say shocking) is that as you look at the work of the pioneers–William Gilbert, Alessandro Volta, Luigi Galvani, Hans Christian Oerstad, Andre Marie Ampere, George Simon Ohm, Michael Faraday, Heinrich Hertz, and on up to the present day, nearly every advance has been a matter of luck. Yes, of course, hard work. But luck, too.

Take the basic element of the electronic world, the transistor. The Bell Labs semiconductor group of Bardeen, Brattain and Shockley (all of whom would win Nobel Prizes) thought the key to the transistor was in the extraction of an extremely pure slab of silicon, from which thin slices could be cut.

But it was only after a lab technician incorrectly cut a slab, so that a thin layer of impure silicon spread across the top, that their oscilloscopes leapt with a surge of electrons. Suddenly they got it—Eureka!—they needed this slice of impure silicon to make the rest of it work. Had the technician not made a mistake, they wouldn’t have realized it. Another group of scientists may have created the transistor first. Then that group would have been great. They would have had their pictures posted prominently on the walls—and the team of Bardeen, Brattain and Shockley would have been consigned to the dustbins of history.

So luck is the lightning bolt that creates greatness. It’s true of writers as well. Please remember that when Melville finished writing Moby Dick (and talk about sweat equity) he was rewarded in his lifetime with sales of about 3,000 copies. Or how about O. Henry? Went to his grave broke. Even F. Scott Fitzgerald found tepid reviews and no sales for The Great Gatsby. In their cases, they had to be dead before the lightning bolt struck. And, of course, there are countless other authors for whom the lightning bolt never struck at all. If you’ve been working away at a new book lately, this may be a bit of depressing news

But the upside of this is that since greatness is largely out of your control, you can relax. Just get on with your writing, for your writing’s sake. And keep at it, for goodness sake. “What I’ve learned, above all,” says scientist Leonard Mlodinow, “is to keep marching forward—because the best news is that since chance does play a role, one important factor in success is under our control: the number of at-bats, the number of chances taken, the number of opportunities seized.”

But the upside of this is that since greatness is largely out of your control, you can relax. Just get on with your writing, for your writing’s sake. And keep at it, for goodness sake. “What I’ve learned, above all,” says scientist Leonard Mlodinow, “is to keep marching forward—because the best news is that since chance does play a role, one important factor in success is under our control: the number of at-bats, the number of chances taken, the number of opportunities seized.”

Who knows–you may be next on luck’s gravy train. And don’t think you’re not good enough. As Taleb notes, “Luck is far more egalitarian than even intelligence. If people were rewarded strictly according to their abilities, things would still be unfair—people don’t chose their abilities. Randomness has the beneficial effect of reshuffling society’s cards, knocking down the big guy.” So take heart.