How do you fix greed? It’s a question that’s plagues our country and much of the world right now, although I’m going to talk about America specifically–because let’s face it, where greed is concerned, we Americans are at the top of the charts. In some other countries, corruption and greed in the government is an especially nasty problem, but here in America greed is more or less a core value, something that’s encouraged for every citizen. As a result, we’re the wealthiest large nation in the world and consume a percentage of the world’s resources that’s far out of proportion to our population.

What specifically is so bad about greed? Isn’t it natural, anyway? Even if it isn’t, what can you do if greed is just something bad people embrace?

What’s wrong with greed?

The problem with greed is that it leads to people and corporations trying to amass resources they don’t need and can’t use well, often straining the capacity of the rest of society and the natural environment in the process. It’s not just the multi-millionaire tossing back caviar while homeless families try to survive on canned soup: it’s kids amassing electronic devices instead of going outside and playing with friends, adults trapping themselves in jobs that make them miserable in order to get the larger houses and better cars they think they “should” be able to have, and people whose lives are dominated by abject envy of everyone wealthier or more famous than they are. Greed is bad investments, celebrity idolization, consumerism grown out of proportion, lousy jobs, waste, inequity, and disconnection of us all from one another.

Isn’t greed natural?

We’ve grown to think it’s natural and normal for people to want as much money as they can get, but we don’t really want money at all: what we want is what money gets us, and by this I don’t mean the products and services, but rather things like a sense of safety, power, indulgence, or validation. When we talk of caring about something, we’re saying we have an emotional stake in it. Our emotional stake in money doesn’t have anything to do directly with having the assets: it’s first about answering physical needs—the minimum of food, shelter, health care, safety, clothing, transportation, and education that is the baseline for our society–and second about gratifying unmet emotional needs.

The emotional roots of greed: some examples

Let’s say Ed grows up in a house where his parents only pay attention to him when he accomplishes something–gets good grades or wins a trophy in a track meet, for example. Ed may very well internalize the idea that the only way people will care about him–in fact, the only way he’s actually worth anything–is if he has something to show for it that everyone can appreciate. He may therefore go into a high-income career and spend his money on trophies: trophy house, trophy clothes, trophy vacations, trophy foods … all so that he can impress people into caring about him and so that he can feel worthwhile. This may sound a little pathetic, but consider how many people buy things–cars, houses in the right neighborhood, even certain foods–in order to act out the life they want to be seen leading.

Actual human connection could make all of this trophy-getting unnecessary. If Ed acquires a set of friends who appreciate his sense of humor and determination and don’t care about his money, Ed may come to stop caring about money so much too, which could lead to enormous changes in making his life happier–like living where he really wants to live, doing what he really wants to do, and prioritizing experiences with friends and family or meaningful accomplishments in the world over acquiring things.

Ed’s situation isn’t the only way we get emotionally involved with money. Imagine Deborah, whose childhood was one disaster after another resulting in moves, loss of friends and homes, and other kinds of upsets. Once Deborah gets out into the world on her own, she may prioritize security over all else, meaning that she has to pile up a lot of things and a lot of money so that she will feel safe against things like the layoffs her father went through or the loss of her home to a flood because her parents couldn’t afford flood insurance.

Or imagine Nick, who was awkward and shy as a kid and ended up being the butt of everyone else’s jokes. They won’t be laughing at him when he pulls up to the high school reunion in a Ferrari while wearing a twenty-six hundred dollar suit, now will they?

Or Andrea, whose parents gave her all the physical things she wanted but left her actual care to a string of nannies and boarding schools. As an adult, Andrea buys anything she wants, whether she can afford it or not, because she “deserves” it–constantly trying to fill an emotional void with things, and probably failing just as badly as her parents did no matter how delightful that first, brief glow of pleasure may be.

That’s not nearly the whole list, but I hope my point is clear: the roots of greed are emotional ones. People want to feel safe, loved, valued, validated, and respected. In different ways, money promises all of those things, even though it often doesn’t deliver.

Are greedy people bad people?

It’s tempting to write off anyone who acts greedy as simply a bad person, yet there’s a more exact and constructive way to look at the problem. First, problem behaviors like greed usually come from people trying to meet their emotional needs, which is a pretty understandable thing to try to do, even if somebody hasn’t chosen a very successful method.

Almost all people who act greedy also do things that we would admire in their lives–they might parent their children well, give to charities, have a strong work ethic, work for causes, help friends and neighbors, have a lot of integrity, or otherwise show their true value.

Writing these people off also means writing off whatever part of ourselves might agree with them, the part that may covet clothes or free time, travel, cars, expensive foods, luxury, or even having a lot of money to help other people with.

Writing off anyone who acts greedy is wasteful, too, because if people can learn not to be greedy, as surely seems to be the case even without the fictional or legendary examples of Siddhartha and Ebeneezer Scrooge, then there’s a powerful reason to try to find ways to fix greed: if a greedy person becomes a non-greedy person, we’ve gained an ally–sometimes a powerful one.

In the next part of this series, I’ll take a look at how greed is entrenched in American culture and what would be necessary to root it out.

Photo by subsetsum

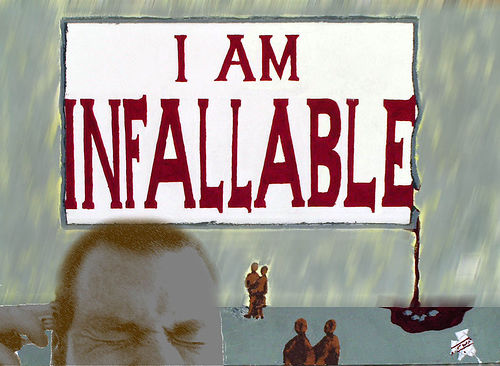

The Punitiveness schema is a lifelong conviction that people should suffer if they don’t follow the rules. People with this schema feel the responsibility to be angry and to ensure punishment is given out, whether to family members, employees, acquaintances, strangers, or themselves. They tend to feel they have a strong moral sense and that their insistence on punishment is about justice and fairness, and they have a hard time forgiving other people or forgiving themselves. They don’t generally consider reasonable circumstances that could explain what they see as bad behavior, and the idea that people are imperfect and just make mistakes sometimes doesn’t usually enter into their thinking. The standards applied in a Punitiveness schema are usually pretty high, too. Wiggle room is a foreign concept.

The Punitiveness schema is a lifelong conviction that people should suffer if they don’t follow the rules. People with this schema feel the responsibility to be angry and to ensure punishment is given out, whether to family members, employees, acquaintances, strangers, or themselves. They tend to feel they have a strong moral sense and that their insistence on punishment is about justice and fairness, and they have a hard time forgiving other people or forgiving themselves. They don’t generally consider reasonable circumstances that could explain what they see as bad behavior, and the idea that people are imperfect and just make mistakes sometimes doesn’t usually enter into their thinking. The standards applied in a Punitiveness schema are usually pretty high, too. Wiggle room is a foreign concept.