A memoir of what went wrong

With mixed feelings, I’ve been reading Tom Grimes’ memoir Mentor, an account of his life as a writer, especially as concerns his time learning with Frank Conroy, who for some time directed the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. I don’t know if you have heard of Grimes; I don’t think I had. He’s had some partly-successful novels, some reviewed well, some not so well–but Mentor, as he writes it, is an account of his failure as a writer.

His first book felt unimportant to him when it came out, but it got excellent reviews in some very important venues. However, as far as I can tell it didn’t make him much money or do much to combat his desperate struggle to prove his self-worth. (I’m not inferring what he thinks here; Grimes is extremely candid about his feelings in the book.)

His second book was finished with huge expectations of success, but from the beginning of its publishing journey yielded mixed signs and mixed reviews. In the end, it appears, it made back only 10% of its advance, which is certainly a financial failure, and also a sharp slap to the face for the writer.

His memoir seems to have gotten some good reviews, although judging by the Amazon ranking at the time I read this, it isn’t taking the world by storm.

Failure seems to be a huge and important subject for Grimes. Reading his memoir at this particular moment, as I’m about to launch into a new project that’s not like anything I’ve attempted before, may be a very good thing for me, because it’s good to face the failure bogeyman right at the beginning.

Is that you, Failure?

I should explain about the new book: for several years I’ve been researching the psychology of motivation and habit intensively. For about ten years, I’ve been writing prolifically and working to build a career as a writer. I had planned on being a professional writer since the third grade or earlier. But of course “writer” isn’t a position like “systems analyst” or “pastry chef,” where you can get a job, go in to do it each day, and feel more or less successful every time you bring home a paycheck. It’s more like being an entrepreneur, or a salesperson who works only on commission, or a painter: you put everything you can into each new project, and then innumerable people other than you–customers or end users or the general public–decide whether it will succeed or not. This would be easier to take, I think, if it were always clear that it was only this final audience that made the decision–that books always sell well when they’re well-written, or that a quality widget sells itself–but unfortunately there are also gatekeepers, timing issues, competing or distracting products, editors or agents or supervisors or clients getting sick or getting pregnant or moving on, good or bad marketing, and all the rest.

Why does a book fail?

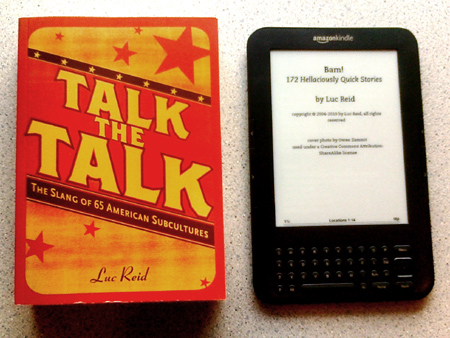

If you write a book and it flops, how do you account for it? Did the book just suck? Or to speak more gently, perhaps the book didn’t have a large enough audience to succeed? Or maybe the publisher didn’t get the book out to reviewers as they were supposed to do (as happened to a friend of mine with an excellent trilogy of his that is still attracting new readers, despite rather than because of the original publisher)? Was it marketed to the wrong audience? (It could be argued that my book Talk the Talk: The Slang of 65 American Subcultures should have been marketed as a general interest book rather than only, as it was, to writers–but that was potentially my mistake and my agent’s in placing it with a publisher that specifically caters to writers.) Was it released at a bad time? Was it mislabeled or miscategorized? Did that awful cover doom it (though I was very pleased with my book cover)? And so on.

I don’t know about you, but I would love to have hard numbers on that. If I were to put out a book that only earned back half of its advance (this hasn’t happened to me; my first book earned modestly more than the advance–but hey, look at me being so quick to assure you that I’m not a failure.) I would want to know why, if it were possible, even if the answer was that the cover and the marketing strategy only accounted for 7% of the failure and the rest was squarely on my shoulders.

But here’s what I assume: I assume that a book most often succeeds or fails on how much the text itself makes people want to read it. There are exceptions: for instance, while I’m sure The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo is a fine book, it seems likely to me that its continuing success is fueled in part simply by the fact that it’s selling so well, as potential readers think “Well, it’s got to be good: millions and millions of people are reading it.” In a way, success builds success.

And obscurity builds obscurity. If no one knows about a book, the chance that they’ll stumble on it and pick it off a knee-height shelf at Barnes & Noble where a single copy is wedged in between books by two other obscure authors, or that they’ll dig it up and buy it from Amazon despite no one having rated it and it showing up at the bottom of the search results based on nonexistent sales, is poor. To some extent success for a book requires an inciting incident–or better, a dozen of them–meaning a review in a venue that a lot of people read, a news story, a mention in mass media, an event, piggybacking on the success of something else (especially the author’s other books), an ad in the right place (if ads really do help books), etc.

But now I’m just rambling about the publishing business, of which I know something but not nearly as much as a lot of other people who blog on the subject much more skillfully (Nathan Bransford comes to mind, for example). What I really want to talk about is the role of failure in a writer’s life as it affects self-motivation.

Failure: not as bad as death

No writing failure is complete if the author is not dead, in which case literary success takes a distant second in importance to being deceased as far as the author is concerned. The nature of a failed book is usually that hardly anyone has heard of it. This is merciful: as writers, it’s our successes that are well-known, while our failures tend to be of great interest mainly to ourselves and our publishers. Not so with movies, for instance. Will Bennifer ever live down Gigli? I’ve never seen the thing, don’t know what it’s about, and had to double check to be sure I got the “Bennifer” thing right, and yet here even I am making fun of it. Obscurity is nice sometimes, if you ask me.

So here I am entering on this book project, and it’s higher-stakes for me than previous ones. First, it carries the weight of years of investigation into the human mind, and if the book doesn’t fly, there’s a temptation to imagine that effort to have been a waste (though it’s already repaid me several times over, truth be told).

Second, it carries the weight of a decade of very serious writing efforts and a couple of decades more of on-and-off writing before that. If I can’t write a successful novel after all this practice, study, hard work, and even networking, what the hell is wrong with me?

Third, the new novel will be a mainstream novel, not a science fiction or fantasy novel. In fantasy and science fiction, it seems to me, we don’t take ourselves with the deadly seriousness I often associate with mainstream (let alone “literary”) writers. The F&SF community is comfortable and friendly and already understands that one failed novel does not determine a career. If I were to get a $5,000 advance and just barely earn out with a fantasy or science fiction novel, it would more or less be a success. This is not my feeling about a mainstream novel. I’m bidding for a wider audience, and it’s a churning metropolis of authors rather than a friendly neighborhood.

Embracing the whatever

And yet … this book can fail. That’s OK. I can put a year into writing it and two years into seeing it sold and published, assuming it even gets that far, and end up back where I started or worse, and that’s still OK. Believe me, I won’t be pleased if I get that outcome, but it’s possible whether I like it or not, so I intend to accept this from the outset, and that gives me strength. Not fearing what will happen, I don’t have to cling to ideas about the novel that seem essential for its success (but which, as I don’t really know for sure what will make for a success or not any more than anyone else does, could be its doom). I don’t have to take myself too seriously. I can screw around in the book, please myself, and hope readers will come along.

Fearing failure, I might handle things differently–hold off submitting the book when it’s ready, clamp down on my natural voice out of anxiety that I’ll sound stupid, fail to engage with the book because I don’t want to engage with the fear I would have created around it, and so on. Fear creates resistance: that’s its job. Fear of a predator in a jungle could make us run like hell or fight desperately. With writing, we don’t want to be running from or struggling with: we want to be diving into. It’s hard to execute a good dive into something that scares you, or when you’re scared of what will happen when you come back up.

So failure: yes, possible. Maybe every book you (if you’re a writer) or I will ever write will flop miserably–never getting a read from an editor or agent or never selling to a publisher or never getting read even though it’s been published. Maybe I’ll write the best novel in the history of the universe and it will come out in the wrong form at the wrong time and be completely ignored due to an unexpected invasion of the United States by Canada. We could say the same of everything else: every romance has a chance of dying, every child has a chance of being hit by an ice cream truck, every job has a chance of disappearing, every friend has a chance of turning on you. It doesn’t matter. I mean it actually doesn’t matter at this stage. This is the stage where we create and throw things out. When it comes back, maybe it will matter enough to be worth learning from, and maybe not. Sooner or later, if it fails, it will be worth moving on from.

Or maybe this time around it won’t be failure: it will be wild success. Maybe every major thing you try to do from this moment on will succeed beyond your wildest dreams. Who can know for sure? For now, I think I’ll ponder that.

Photo by blmiers2

Like this:

Like Loading...