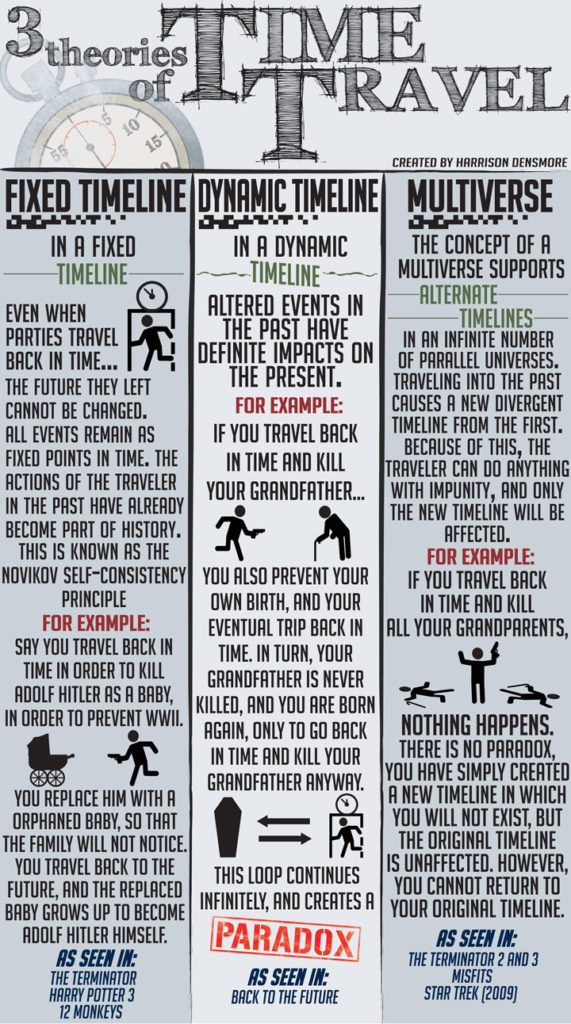

My son, Ethan, posted a neat graphic by Harrison Densmore explaining three approaches to time travel in stories. It’s pretty good, actually. Check it out:

I think this is a great start, but it’s incomplete. There are at least six approaches to past time travel stories. Note that future time travel isn’t such a big deal: we do it all the time, and even know how to speed it up (travel at relativistic speeds).

Here’s the list I know.

- Time travel is impossible. The reason I mention this as one of the options is that a story can be about people attempting time travel, thinking something is time travel that actually isn’t, etc. I wouldn’t be surprised if this turns out to be the real one.

- The self-healing timeline. In this one, you travel back in time and change something, but the universe changes something else to cancel your change out. I’m not a fan of this one, because 1) why does the universe care?, and 2) two changes that cancel out one particular effect are not the same as not changing anything in the first place. For instance, what about the people whose lives would have been affected by the orphan?

- The timeline that’s smarter than you. This is the one Densmore calls “The Fixed Timeline.” In this one, any changes you make were what happened all along; you just didn’t realize it. Maybe you shot and killed your grandfather, and it turns out that wasn’t your grandfather at all, that’s just what grandma told your dad when he was growing up. I’m not crazy about this approach either, because it requires existence of some kind of intelligent Fate and imposes arbitrary limits on human intelligence. Humans may be intellectually limited, but we’re not stupid. Except sometimes, but that’s another discussion.

- Dynamic timeline. Densmore covers this one nicely. I think nature abhors a paradox, but you can still get fun stories out of this.

- Multiverse. This is the easiest one to work with, although I’d point out that some multiverse stories don’t restrict universe-hopping–so you might spawn a new version of the universe and experience it as long as you stay there, but be able to come back to your original timeline because your machine or magical ability or what have you is just that good.

- The elastic timeline. In this timeline, you can go back in time and do whatever you want, and the world will change accordingly (e.g., no baby Hitler), but when you return to your original time, nothing will have changed. In this approach, the universe is assumed to have some kind of resilience, or time travel to occur in some kind of pocket universe that vanishes when you leave it. I have an unfinished story that uses this approach in which a young man regularly travels back in time to kick the living crap out of horrible dictators from the past–just appears in Francisco Franco’s bedroom, for instance, and goes to town on him with steel-toed boots. As you can imagine, he comes to find this approach to happiness flawed.

So … what did I miss?

This is the seventh interview and the ninth post in my series on inclusivity and exclusivity in fiction. You can find a full list of other posts so far in the series at the end of this piece.

In today’s post, I talk with British Science Fiction Association award-winning French/Vietnamese writer Aliette de Bodard about writing, reading, cultural divides, and the bridges that span them.

LUC: Just to bring your work to science fiction and fantasy readers in North America, you’ve had to bridge a number of gaps–ethnic, linguistic, geographical, and more. Does this affect how you choose your characters and how you think about writing?

LUC: Just to bring your work to science fiction and fantasy readers in North America, you’ve had to bridge a number of gaps–ethnic, linguistic, geographical, and more. Does this affect how you choose your characters and how you think about writing?

ALIETTE: I have to admit that I didn’t quite think of it that way! For starters, I was hardly aware of the SFF market as being sharply compartimentalised when I started writing–and, if anything, I would have targeted my work at the UK market, since that’s where I started reading most of my genre. I also seldom think in terms of gaps when writing: rather, I write passionately about things that matter to me, and trust that this enthusiasm will communicate itself to the reader.

But yes, if we’re talking quite plainly–of course my origins, my personality and the milieu I grew up in and am still part of deeply and irrevocably approach how I’m choosing characters and how I think about writing. I would be a very different person if I had grown up white on the US East Coast–my family, my education, my friends, etc. have shaped me as a writer, and continue to shape me.

I tend to pick characters from non-mainstream backgrounds, mainly because I’m somewhat disquieted by how SF, which should be the literature of the mind-blowing and mind-opening, tends to over-feature characters from a certain background (overwhelmingly male, white and American or Western Anglophone) and from a certain mindset (what I would call “tech-loving” with a strong faith that science will make things better). Not, of course, that I have anything against those views myself, but the over-representation of these can be a little overwhelming in the bad sense of the term…

I approach writing as the sum of everything that I have read, which means traditional French/English/Vietnamese/Chinese literature as well as genre from Ursula Le Guin to Alastair Reynolds to Jean-Claude Dunyach. Reading so much in so many traditions has enabled me to see that the “rules” of writing (like “show don’t tell”) are deeply problematic because they enforce the conformity of a certain type of fiction–they’re a great help as you’re starting out, but taken too rigidly they can easily lead people to stifle their own creativity in the search of the technically perfect, but soulless story.

It’s hard for me to tell how much my approach to writing is shaped by my background and which specific bits are “different”–I know that I place a high importance on family in my fiction, and immigration and living between different cultures (obviously a very personal preoccupation!), but I assume there are more subtle effects on themes, characters and storylines that I’m not able to see because I’m too close to them.

LUC: There are a lot of interesting threads in that response, but let me grab onto one particular one, because I don’t think it’s ever even come up in this discussion for me until now: science fiction tending to include people of a certain mindset. I had never thought of it that way before, but it strikes me immediately as having a lot of truth to it. When science fiction stories emphasize strongly tech- and science-friendly characters, what points of view would you say aren’t getting a lot of representation?

LUC: There are a lot of interesting threads in that response, but let me grab onto one particular one, because I don’t think it’s ever even come up in this discussion for me until now: science fiction tending to include people of a certain mindset. I had never thought of it that way before, but it strikes me immediately as having a lot of truth to it. When science fiction stories emphasize strongly tech- and science-friendly characters, what points of view would you say aren’t getting a lot of representation?

ALIETTE: Hum, it’s one of those questions where I don’t think I can give a complete answer to, but I can provide a few examples… By and large, SF is mainstream US, 21st-Century and tech-loving, which means that anything outside those points of view is getting poor representation. I can mention a few things that struck me, beyond the most obvious ones of poor POC/female/non-US representation, but this is obviously very limited!

- the paucity of stories where family is important, and in particular family outside the nuclear family (SF sometimes gets around to mentioning fathers and mothers, but aunts, uncles and cousins somehow seem beyond the realm of possible relationships)

- a marked dichotomy between allegiance to a church or allegiance to science, generally failing to recognise either that the two points of view are not incompatible, or that religion doesn’t necessarily mean full allegiance to a church (in many Asian countries, people practise bits and pieces of religions depending on the circumstances, and don’t refer to a single church for prescriptions on every aspect of their daily lives)

- a presentation of individualistic, lone mavericks who strike out to seek adventures as intensely heroic, and a deriding of people who do not follow that mindset as being cowardly (in Asian culture, people who abandon their families to strike out would be the cowards because they shirk their duties to provide for their relatives, and the act of falling out with your own family would be a tragedy rather than a cause for celebration).

LUC: Recently on your Web site, you quoted Juliana Qian:

Our cultures are exotic, fashionable, fascinating and valuable when contained within or filtered through a white Western lens – then our cultures are glittering mines. But drawing from your own background is backward and predictable if you’re a person of colour. Sometimes white people try to sell me back my culture and I have to buy it. My China is as much the BBC version as it is the PRC one. There are things I want to eat but cannot cook.

This brings up the question of how different it is for someone within a group–whether we’re talking about, for example, Russians, transgendered people, or people with physical handicaps–to write about that group than for someone outside in terms of how the writing itself is viewed. How does this affect your work, or the work of other writers whose work you follow?

ALIETTE: It’s all but inevitable that someone within a group will perceive it in different terms than someone outside a group: it’s what I call “insider” writing vs “outsider” writer. There are two different problems: who is writing this, and for whom it is intended. I’ll leave aside the obvious combinations of outsider writer for outsiders only (which is a very dodgy proposition and fairly exclusionary) and insider writer for insiders only (posing no particular issue: write what you know for people who know it as well). That leaves the “crossing overs,” i.e., outsider writers writing for an audience which includes insiders and insider writers writing for an audience which includes outsiders.

If you’re an outsider, it is possible to achieve a sufficient degree of empathy with the group to make your depiction of it from the inside plausible, but it takes a lot of hard work, and I think people don’t understand how seldom this happens: the authors who pull this off, say, for Vietnamese culture, can literally be counted on the fingers of one hand, and generally have thoroughly immersed themselves into it for years. A few more authors will produce a passable description, and the bulk will unfortunately perpetuate majority stereotypes or latch onto what seems to them shiny elements of a culture–elements that are totally natural to insiders (one of my favourite examples from Sino-Vietnamese culture includes the over-emphasis on face, which is an unconscious thing–people don’t spend their time going, “oh, I’m going to lose face if I do this” every two lines!). Hence the importance of thinking very carefully about what you’re doing when depicting a culture and of getting beta-readers from said culture to correct you.

If you’re an insider, you have a slightly more difficult problem. I’ve already said that the elements of a culture that appeal to outsiders are not necessarily the ones that insiders think most important, and also that many things that seem natural to you (like food) will require explanation in order to make sense to outsiders. There’s a hard line to draw between making your culture a little more “accessible” to outsiders, and between twisting it out of shape so it appeals to the market.

In my work, I’ve done outsider and insider depiction: when I do outsider (such as in the Aztec books), I do my best not to exoticise or demonise practises that the main characters would have found totally natural, like human sacrifices. When I do insider writing, I find myself very often having to explain behaviours and attitudes that are perfectly normal to me, but that make no sense to outsiders (like filial piety or Confucianism): the first draft of my novella “On a Red Station, Drifting” basically had every (non-Vietnamese) reader terminally confused, and I had to do my best to clarify what I meant without having the impression that I was putting the “crunchiest bits” of my culture on display for Westerners (I enjoy writing about my background, but I certainly don’t want the feeling that I’m debasing it in order to sell better!).

LUC: I was interested when you mentioned those authors that you could count on the fingers of one hand, because while we’ve all seen examples of mishandling of other cultures, examples of people who do the job really well seem harder to come by. Are there any writers that come to mind to you offhand who really do an exceptional job, whether they’re outsiders whose writing rings true to insiders or insiders who make a real connection with outsiders?

ALIETTE: It’s going to be hard for me to point out outsiders who really do insider narrative well, as I can’t really appreciate anything beyond France and Vietnam in fiction; and a lot of portrayals of both, as I said above, are very debatable to say the least. That said, one of the works I thought did a great job of evoking the spirit of 17th-18th Century France was Kari Sperring’s debut, Living with Ghosts: the intricate plot and delicately-drawn characters made me think of a modern-day, more nuanced Dumas.

There are more than a few people who are insiders and who create a real connection with outsiders: the first one who comes to mind is the unstoppable Ken Liu, whose fiction is basically everywhere, and who creates really strong stories driven by Chinese culture. I can also cite Rochita Loenen-Ruiz, whose idiosyncratic Filipino SF is bound to make a huge splash (check out her “Alternate Girl’s Expatriate Life“, which tackles emigration, mixed marriages and power dynamics in a very spec-fic way), and Zen Cho, who has a knack for mixing comedy and poignancy in really well-realised stories (her “House of Aunts” is a really awesome not-quite-our-vampires story).

As far as novels go, can I point out to Thanh Ha Lai’s truly awesome “Inside Out and Back Again”, which shows emigrating to America from the point of view of a young Vietnamese girl and the resultant culture shock; and to Joyce Chng’s Wolf at the Door and sequels, urban fantasy set in a vibrant and rich Singapore and featuring a very strong main character in the presence of werewolf pack leader Jan Xu.

Aliette de Bodard lives in a flat with more computers than warm bodies, and writes speculative fiction in her spare time–her Aztec noir fantasy trilogy Obsidian and Blood was published by Angry Robot, and her short fiction has garnered her a British Science Fiction Award and nominations for the Hugo, Nebula and Campbell Award for Best New Writer. When not writing, she blogs and posts recipes over at www.aliettedebodard.com

Aliette de Bodard lives in a flat with more computers than warm bodies, and writes speculative fiction in her spare time–her Aztec noir fantasy trilogy Obsidian and Blood was published by Angry Robot, and her short fiction has garnered her a British Science Fiction Award and nominations for the Hugo, Nebula and Campbell Award for Best New Writer. When not writing, she blogs and posts recipes over at www.aliettedebodard.com- 7/27 – interview with Leah Bobet

- 7/29 – Where Are the Female Villains?

- 8/3 – interview with Vylar Kaftan

- 8/9 – Concerns and Obstacles (multiple mini-interviews)

- 8/10 – James Beamon on Elf-Bashing

- 8/17 – Steve Bein on Alterity

- 8/24 – Anaea Lay on “An Element of Excitement”

- 9/21 – Leah Bobet on Literature as a Conversation

A writer friend/acquaintance whose work I quite like was discussing a short fiction project (the Daily Cabal, which is very, very short science fiction posted every weekday morning) today and said “For some reason I can’t quite fathom, most of SF readers are also SF writers.”

Another friend pointed out that a great many of the people discussing short science fiction online are science fiction writers. That might be true (again, it would be very hard to get statistics), but the people who discuss reading science fiction aren’t likely to be a random cross-section of the readers of science fiction. Writers are much more likely to discuss writing than non-writers, after all.

In the end, I have no statistics on this, but I think the thing to take away is to have great caution about what any personal sampling of readers tells you unless that sampling is somehow a cross-section reflective of an entire readership. The people who write letters to the editor at the newspaper are not the average newspaper readers; they’re an unusual group within newspaper readers. The people who come to signings tend to be the most die-hard fans, not the person who picked up your book because the cover looked interesting and there was nothing good on TV. If you’re a writer, your friends who read are very unlikely to be typical readers.

I mentioned touching a nerve earlier: maybe it’s more accurate to call it a pet peeve. I don’t like it when writers go out of their way to market their fiction to other writers. To friends, sure. To your writing group, sure. But don’t go and put up a post about your latest short fiction sale being out in bookstores now on a public writing discussion group; don’t give out swag at writer’s conferences. Just because writers are readers and are easy to find doesn’t mean that they’re where you should be putting your effort. How far can we really get, taking in each other’s laundry? Besides, it’s a market that gets far too many advertisements.

Even a blog about writing is a questionable enterprise from a marketing point of view. If you’re writing about writing because it lets you market your new novel to amateur writers, this is just the laundry thing again. Figure out what kind of readers you have and go market to them, says I.

Which may bring you to wonder what I think I’m doing with this writing blog. Well, there’s a good justification for it on the one hand and a real reason for it on the other. And then, of course, there’s the real real reason for it.

The justification is that my first book (Talk the Talk: The Slang of 65 American Subcultures) is a book for writers. It’s of interest to a lot of people who aren’t writers, but it was written with writers especially in mind and is published by Writer’s Digest books. So I’m in the unusual situation of being a writer whose market is actually writers. It’s as though I specialize in cleaning launderer uniforms, which is a legitimate niche trade.

The real reason is that for years and years I’ve been profoundly interested in learning about writing and in spreading the knowledge. That’s why I started Codex, and I hope to be able to be of some use to writers here.

And the real real reason is that I like to mouth off about my writing opinions in a semi-irresponsible way and need a forum in which to do it.

There’s probably another reason behind that somewhere, but that moves out of the realm of writing and into the realm of psychotherapy, and there’s no need to get ridiculous with it.

There’s an old and revered legend that circulates among science fiction and fantasy writers, and it goes like this: “A lot of people won’t read science fiction just because it’s labelled ‘science fiction,’ so publishers call some science fiction ‘mainstream’ and then people will read it, but it’s really science fiction.” Optionally, the legend may include “Authors who won’t call their work science fiction are selling out.”

The same thing is said about fantasy; I’ll deal with science fiction here for convenience, but the same arguments apply.

As you can probably tell from the title of this entry, I don’t exactly agree with this idea, and I think the exact reason the ghetto is a myth leads to an important thing for writers (at least science fiction and fantasy writers) to understand, of which more in a moment.

What books are we talking about here? Margaret Atwood (for instance, The Handmaid’s Tale) and Kurt Vonnegut (Slaughterhouse Five, for example) get a lot of mentions in this context. More recent examples include Maria Doria Russell (The Sparrow) and Gregory Macguire (Wicked).

Here’s how people seem to look at this: if a story is set in the future (like The Handmaid’s Tale) or contains science fictional elements (like the interstellar flight in The Sparrow), it’s science fiction. If science fiction is defined solely by subject matter, that makes sense. But is that the most useful definition of science fiction? I’m big on “useful.”

Think about it this way: as a reader, which of the following is more important for you to know about a book?

A) Exactly what subject matter it contains, or

B) Whether or not you’re likely to enjoy it.

Or as a writer, which of the following do you care about more?

A) A taxonomic classification of your book based on an analysis of story and setting elements, or

B) Who will buy your book.

In both cases, we have a choice between A, which gives us rigid categories that take into account only certain aspects of a book and B, which gives us information about what books are good for what people.

A and B are not equivalent. Putting a spaceship into a story doesn’t necessarily make it appealing to all science fiction readers, and for many readers, how a story is told counts for a lot more than what props show up in it or when it’s set.

I’ll use the term “mainstream science fiction” here to describe stories that contain elements we usually associate with science fiction but that are written for a general audience instead of primarily for science fiction readers.

So, recently a writer friend and I were discussing Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow, which I’d call “mainstream science fiction,” and Hyperion, by Dan Simmons, a novel that’s clearly labelled and read as science fiction. My friend asked what I thought made The Sparrow mainstream science fiction and Hyperion genre science fiction. My answer was this:

1) The Sparrow focuses on the story and characters rather than the speculative elements. The speculative elements are background rather than foreground.

2) The Sparrow presents speculative elements gently, in ways that mainstream readers find easier to adjust to. No terms are thrown out without indications of what they mean. No speculative elements are introduced simply for coolness factor: they are streamlined to the essentials required to tell the story.

I readily admit that these aren’t hard-and-fast distinctions, but they’re meaningful distinctions to readers.

Here’s the opening of The Sparrow:

On December 7, 2059, Emilio Sandoz was released from the isolation ward of Salvator Mundi Hospital in the middle of the night and transported in a bread van to the Jesuit Residence at Number 5 Borgo Santo Spirito, a few minutes’ walk across St. Peter’s Square from the Vatican.

And the opening of Hyperion:

The Hegemony Consul sat on the balcony of his ebony spaceship and played Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in C-sharp Minor on an ancient but well-maintained Steinway while great, green saurian things surged and bellowed in the swamps below.

In Hyperion, we’re supposed to take a variety of speculative elements (the existence of some sort of Hegemony; big, green monsters; and a spaceship with a balcony) in stride.

In The Sparrow, the only immediate speculative element is the date, and that is immediately comprehensible to everyone. Russell failed to take the initiative to come up with a more plausible future vehicle than a bread van or to create a brand new religious order. Throughout the rest of the first chapter, there is only a reference to a mission to a place (the reader will probably conclude that it’s a planet) called Rakhat, and a mention in passing of the fairly non-speculative effects of travelling at near light speed.

Hyperion has several times as many speculative elements on the first page as The Sparrow has in the entire first chapter. Actually, Hyperion has more speculative elements in the first sentence than The Sparrow has in its entire first chapter!

The essence of mainstream science fiction as compared to genre science fiction is how it expects its readers to deal with speculative elements, their tolerance and ability to grok them. So mainstream vs. genre is a meaningful distinction that is useful to readers, because it helps them select books that are or are not suited to their tastes. Some genre readers aren’t interested in mainstream fiction because it doesn’t have enough wild stuff. Some mainstream readers aren’t interested in genre fiction because it asks them to do things with their brains that they don’t like to do and that their brains aren’t currently good at.

Why is this important to writers? Because while every book you write has to be a book you love, you also have to know who else out there in the world will read it. If you want to reach a larger audience, you have to tell your story in a way that they will be willing to read. If you want to reach science fiction readers, you need to tell the story in the way that they want to hear it told. And these are basic writing choices rather than simply labels slapped on by publishers.

From here we get into trickier questions, like the Harry Potter stories. In a sense, Harry Potter stories are clearly fantasy: they throw out a lot of magical things and don’t explain everything. But they still don’t demand the reader to juggle ideas in the way the usual adult fantasy novel these days does, in part because there’s no attempt to justify the magical system. Thus the Harry Potter books manage to be mainstream books in the same way a science fiction movie like Independence Day, which doesn’t require audiences to imagine anything radically new, is a mainstream movie.

But there’s a subtler point here, which is that if you can make the payoff high enough, you can ask more of your readers (or viewers). Many kids and adults who wouldn’t have been interested in reading a fantasy story under normal circumstances simply got so much enjoyment out of Harry Potter that they were willing to accept his impossible world, just as many of Michael Crichton’s readers will sit still for discussions of reconstructing DNA because later in the story, they get to see characters they care about running from a ravenous T-Rex.

The lessons I take from all this are as follows, then. Rule one: write a story in a way that readers are willing to read it. Rule two: if you can write a story that fascinates people, you can break rule one and any number of other rules. Rules aren’t made to be broken, but you could argue that in writing, they are made to be transcended.