My First Published Book–and Publisher Problems

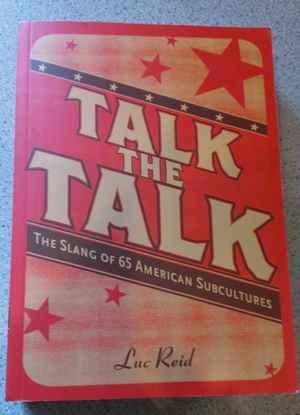

My first published book was Talk the Talk: The Slang of 65 American Subcultures, a dictionary of and guide to subculture slang in the U.S., appearing in bookstores in 2006. I received a small advance and an education in traditional publishing. My publisher’s royalty statements tended to be late when they came at all, and they didn’t appear to be very consistent or accurate. Eventually the publisher put out an entire separate printing, a hardcover version, that they neglected to mention to me–or pay me for. I didn’t know about it until I walked into my local bookstore and saw a bunch of copies of my own book. “Hardcover?” I said. “This was never released in hardcover!” Of course, it had been.

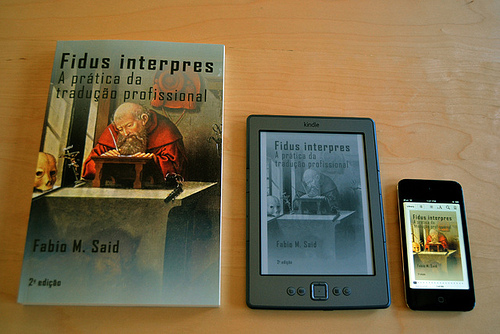

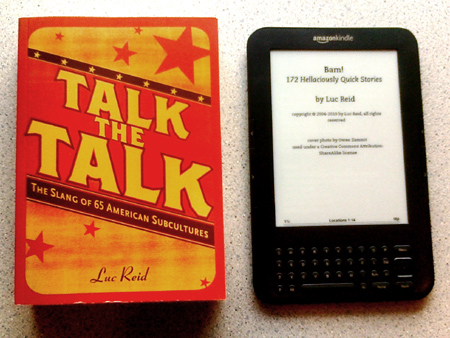

I did eventually get paid some of those royalties, but as the book came to the end of its life cycle and it started appearing on bargain tables, I turned my thoughts to rights reversion. Reversion is when a publisher assigns all of the rights for future editions of the book back to the writer, whether due to a prior arrangement, out of the goodness of their hearts, or perhaps as a peace offering to a writer whose book they have published in a separate hardcover edition without his knowledge or permission. Whatever the reason, Kindle books were starting to make a splash, and I wanted to make a proper Kindle edition of Talk the Talk.

The publisher did, kindly enough, agree to revert the rights for the book to me, and I started on an updated edition that I could release in paperback and for Kindle, figuring that I could probably have it out in a month or two.

Out with the old

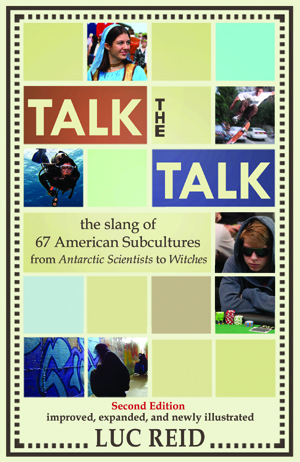

Two and a half years later, I’m finally finished with that new edition: after a long time spent editing, updating, programming, formatting, checking, and tweaking, and with a cover based on a design very kindly donated by my talented artist cousin Nicholas, I’ve approved the proof, and the book is available for order.

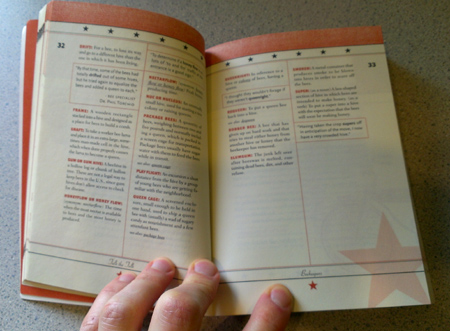

The new edition is Talk the Talk in as ideal a form as I can imagine. The original edition was beautifully designed, with a sort of Soviet Rodeo aesthetic throughout and I thought it was very snazzy, but unfortunately it was also difficult to read and wasteful of space. Because of that design, I had to cut out a lot of material out from the original edition. I was also concerned that it wasn’t too comfortable to read in large sections (for people who wanted to do that), however pretty the design was.

interior of the original 2006 edition

In the new edition, I’ve dispensed with the Soviet Rodeo design (which I probably wouldn’t have had the rights to use anyway) and made the book much clearer and more comfortable to read. I restored a bunch of material that I’d had to cut out of the original, and removed a section the editor had really wanted that I didn’t feel belonged in the book because it was more popular culture than subculture (I’ve made the original version of that section, on hip hop slang, available for free on the book’s Web site at www.subculturetalk.com). I added some new sections on subcultures like geocachers and scrapbookers and painstakingly sourced and included well over a hundred photographs illustrating people, concepts, and items from the many subcultures in the book.

The old edition is 5″ x 7″ and 422 pages. The new edition, which I really like, is 5.25″ x 8″ and 620 pages. The ebook is much less expensive than the original, and the paperback costs a little more than the original did.

The old edition is 5″ x 7″ and 422 pages. The new edition, which I really like, is 5.25″ x 8″ and 620 pages. The ebook is much less expensive than the original, and the paperback costs a little more than the original did.

Shouldn’t I Feel Triumphant Now?

Completing the book doesn’t feel real to me yet. It’s true, I didn’t work consistently the whole two and a half years just on editing, expanding, illustrating, and formatting this book–but I did spend many months at all of that work. Everything took much longer than expected. Once the Kindle eBook was finally ready in January, I figured it would be a walk in the park to use the database system I had created for the book (which automatically managed cross-references, synonyms, indexing, and alphabetization) to output a paperback version. Many, many working hours later, I realized it wasn’t so simple: I needed to spend a lot of time defining and perfecting formatting for all of the different kinds of information in the book, including “see also” terms, synonyms, warning symbols, terms, definitions, examples, photographs, subculture introductions, table of contents, index entries, photo credits, and a lot more. Also, I was very, very picky: I tried to do everything in the best way I could devise.

There had briefly been a Kindle edition of the first edition put out by my original publisher: someone there had apparently forgotten to tell someone else that the rights had reverted to me, and they had just dumped their original layout into a file that made a terrible eBook. I contacted the proper authorities when that appeared and had it taken down, partly because they no longer had a right to publish the book and partly because I thought their electronic version was a mess.

Thew edition, however, has been available for Kindle since January, and the paperback went up for sale today; it will start appearing on Amazon next week.

It’s Hard to Stick With Hard Work

I tried starting several new projects while working on this book, but after a short time on each I always forced myself to stop and go back to finishing Talk the Talk. After all, the book was already “finished,” money lying on the table ready for me to scoop it up–at least, that was the idea. In any case, if I’m going to commit to a project, it doesn’t make sense for me start conflicting projects, no matter how appealing they may be, and no matter how much drudgery needs to go into the current project. Trying to do two such projects at once would only delay both of them. Still, from all of my other writing during this period I now have two mostly-completed non-fiction books in progress, a novel I started and set aside, and many completed short projects (flash fiction, short stories, and plays), some of which were published or produced in this period. I also published a collection of science fiction and fantasy short-short stories called Bam! 172 Hellaciously Quick Stories and a previously completed novel set in my native Vermont, Family Skulls.

Was This a Good Choice?

I’m proud I stuck with Talk the Talk, but it may have been stupid to do so. After all, the amount of work I had to put into the new edition was hugely more than I expected. I’ll have to sell at least a thousand copies to be adequately compensated for all the time I put into just this edition, and that’s getting nothing yet for the value of the book as it existed in the first edition.

When I started, I can’t imagine how I could have known how much labor was going to have to go into releasing this second edition. Given what I didn’t know, the choice to go ahead was obvious. If I had known the amount of work involved, I’m not sure I would have proceeded. Fortunately, I can enjoy having the book out in this form now regardless of how much time and effort it took.

Will I Be Able to Sell It On My Own?

I do have a promotion plan, one that’s quite different from what I’ve done with other books to which I own all rights, but it’s kind of hit-or-miss: it might bring many, many new readers or fail utterly. After all, I don’t have the ins that my previous publisher has. If you have any recommendations for reviewers, magazines, Web sites, or radio shows that might enjoy the book, please comment or contact me through the contact form. If the book gets extra exposure because of you, I’ll send you a free, signed copy.