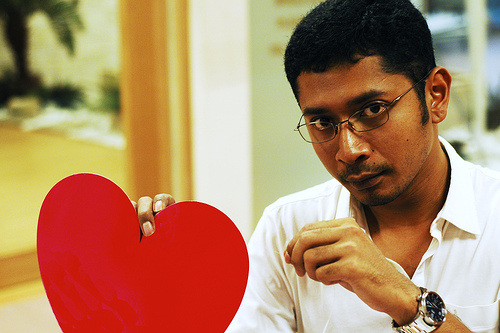

I’ve been doing a lot of reading lately on schema therapy and mental schemas, a subject I’ve written about here a number of times: see links on my Mental Schemas and Schema Therapy page. One of the most intriguing insights that’s come up in that reading is “schema chemistry.” What’s schema chemistry? The short version is this: sometimes the people we are most strongly attracted to are the ones who are the most likely to make us crazy.

I don’t want to overstate this: I don’t imagine for a minute that all love, romance, chemistry, and attraction are based on people fitting their mental baggage together–but it’s pretty fascinating that some of it seems to be, for some people.

The apparent reason schema chemistry happens is that the kinds of troubles we’re used to are comfortable and normal-feeling to us, so a person who causes the same problems we’re used to will feel more familiar and closer. If Mary grew up in a house where her parents always left her alone, she might very well feel more “at home”–not happier, but in more familiar and “right-feeling” territory–if she dates someone who always leaves her home alone, too. If Jack’s mom was always telling him he was a hopeless screw-up, he might have more respect for and feel more familiar with a girlfriend who always tells him the same thing.

According to some accounts in Schema Therapy: A Practitioner’s Guide by Drs. Jeffrey Young and Janet Klosko, it appears this isn’t always a mild effect, either: sometimes it really makes the sparks fly.

As you might expect, this can be bad news. Two people might fall madly in love, have a breathtaking romance, and then settle down into a pattern of gradually making each other miserable. Apart from breaking up, the best hope for a couple like this is often to get couples therapy–I’d be inclined to suggest couples schema therapy specifically–and to learn there not only how to handle their own emotional baggage better, but also how not to push the other person’s destructive buttons.

Here are a few more examples of schema chemistry:

- A person who feels defective (the Defectiveness schema) gets together with a person who feels like people should be punished for even small mistakes (the Punitiveness schema)

- A person with a sense of being better and more deserving than other people (the Entitlement schema) gets involved with someone who is constantly taking care of other people at the expense of their own needs (the Self-Sacrifice schema)

- Someone who grew up feeling lonely and neglected in a house where there was very little nurturing or expression of love (the Emotional Deprivation schema) dates someone to whom expressing emotions seems unnecessary and disturbing (the Emotional Inhibition schema).

There are any number of combinations, given that there are 18 different schemas and a variety of ways to express each one. Fortunately, there are many other factors to bringing two people together than schema chemistry. Here’s hoping it’s not at work in your relationship! If it is, just becoming aware of how the two schemas interact may start to help. I’m working on a short, informal book on mental schemas that I hope will make it easier for people to gain insights on their own and others’ schemas; it should be out in November or December. For information on that, stay tuned.

Photo by jb_brooke