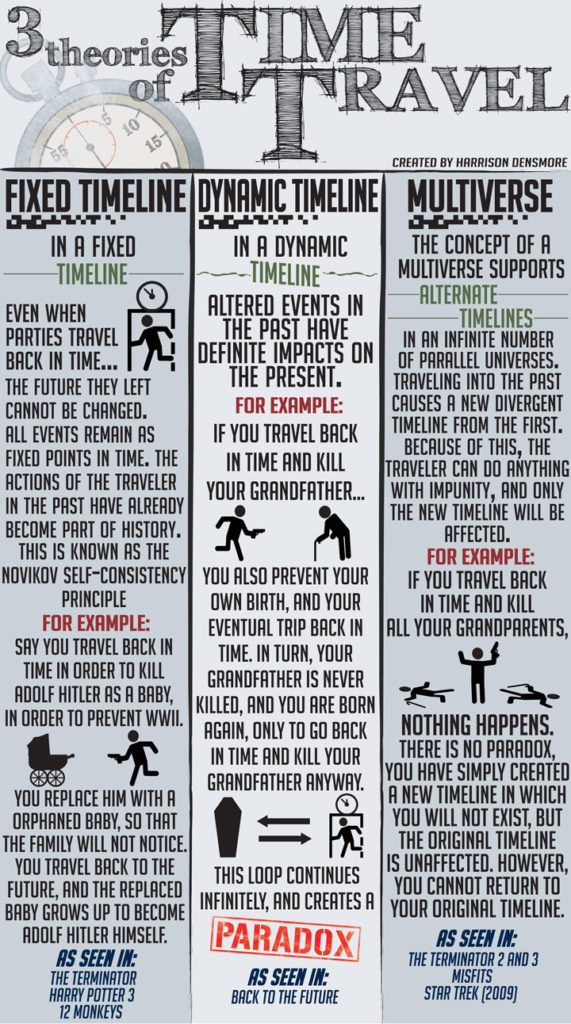

My son, Ethan, posted a neat graphic by Harrison Densmore explaining three approaches to time travel in stories. It’s pretty good, actually. Check it out:

I think this is a great start, but it’s incomplete. There are at least six approaches to past time travel stories. Note that future time travel isn’t such a big deal: we do it all the time, and even know how to speed it up (travel at relativistic speeds).

Here’s the list I know.

- Time travel is impossible. The reason I mention this as one of the options is that a story can be about people attempting time travel, thinking something is time travel that actually isn’t, etc. I wouldn’t be surprised if this turns out to be the real one.

- The self-healing timeline. In this one, you travel back in time and change something, but the universe changes something else to cancel your change out. I’m not a fan of this one, because 1) why does the universe care?, and 2) two changes that cancel out one particular effect are not the same as not changing anything in the first place. For instance, what about the people whose lives would have been affected by the orphan?

- The timeline that’s smarter than you. This is the one Densmore calls “The Fixed Timeline.” In this one, any changes you make were what happened all along; you just didn’t realize it. Maybe you shot and killed your grandfather, and it turns out that wasn’t your grandfather at all, that’s just what grandma told your dad when he was growing up. I’m not crazy about this approach either, because it requires existence of some kind of intelligent Fate and imposes arbitrary limits on human intelligence. Humans may be intellectually limited, but we’re not stupid. Except sometimes, but that’s another discussion.

- Dynamic timeline. Densmore covers this one nicely. I think nature abhors a paradox, but you can still get fun stories out of this.

- Multiverse. This is the easiest one to work with, although I’d point out that some multiverse stories don’t restrict universe-hopping-so you might spawn a new version of the universe and experience it as long as you stay there, but be able to come back to your original timeline because your machine or magical ability or what have you is just that good.

- The elastic timeline. In this timeline, you can go back in time and do whatever you want, and the world will change accordingly (e.g., no baby Hitler), but when you return to your original time, nothing will have changed. In this approach, the universe is assumed to have some kind of resilience, or time travel to occur in some kind of pocket universe that vanishes when you leave it. I have an unfinished story that uses this approach in which a young man regularly travels back in time to kick the living crap out of horrible dictators from the past-just appears in Francisco Franco’s bedroom, for instance, and goes to town on him with steel-toed boots. As you can imagine, he comes to find this approach to happiness flawed.

So … what did I miss?

For live critiquing:

credits

Images: don’t know; didn’t ask

Nonsensical captions: me

James Maxey is the most unrelentingly quotable person I’ve ever met. I complained about this to him the other day in the course of asking permission to post the below. He gave me his blessing to post and mentioned he’d be likely to expand on what he said soon on his own site (see link, below).

“Even I find myself quotable,” he said. The bastard.

Anyway, in a recent writing group discussion, we were talking about why we chose our current projects. There were a variety of answers, but the word “excitement” came up a lot, and James had this to say on the subject.

For what it’s worth, I think mere excitement is a vastly overrated reason to commit to a novel. Excitement is sufficient grounds to take part in a one night stand, but committing to a novel is more like choosing someone to marry. There needs to be that initial passion, but there has to be something stronger beneath it. The novel has to share your values and your long term goals. You have to be willing to stand by it in sickness and health, through riches and poverty. You’re going to see this novel without its makeup on. You’ll have to be there to comfort it when it gets the flu and has bad things pouring out of every orifice. You’ll have to keep believing in it when it hits low points, when it’s lost its way and no longer moves you to passion. You’re going to have to keep going home and sharing a bed with it even though other younger, better looking, more clever novels flirt with you.

The long term rewards of such a relationship make it all worth it. You write the novel, edit it, polish it, and all the time it edits and polishes you. At the very least, you should emerge from a finished novel as a better writer, but I also think it’s possible to emerge from a novel as a better person.

That resonated with me, and James, a prolific and popular writer, is speaking from a lot of personal experience. He’s the author of award-winning short storties and a pair of read-at-a-gulp superhero novels, as well as the Dragon Age trilogy and the very different Dragon Apocalypse series. If you’re curious, check him out at dragonprophet.blogspot.com .

Lon Prater kindly agreed to guest post about Marshall Plan novel writing software. Lon is a friend through the online writers’ group Codex. You can find out a bit more about him and jump to his Web site at the bottom of this post.

Near the end of October 2013, I was given a free copy of the Marshall Plan Novel Writing Software (Mac version) to review. After tinkering with it about 10 weeks, I’m ready to share my thoughts on it.

Some Background

I was first exposed to The Marshall Plan as a set of extremely helpful books by agent and author Evan Marshall. One book focuses on writing your novel, the second on selling it. There are also some workbooks, but I have no background with them. The two main books have a lot of meaty, useful stuff packed inside. Though geared for planners over “pantsers” there’s still a lot of valuable technique to be learned in these books, as well as crunchy good info on the business and career side of selling what you write. There are sections of these books I have gone back to reread no less than eight or nine times over the years.

One of the most specifically structured aspects of the Marshall Plan is a breakdown of how many scenes a book of a given length should have, with some additional consideration for genre, and how the viewpoints should be distributed across those scenes. As you can imagine, this can get incredibly fidgety.

As an example: a 70K Suspense/Crime novel would be broken up into 56 sections, with so many from the point of view of the Lead, the Opposition, and the Romantic Involvement—each happening in a specific (but not confiningly rigid) order. Pivotal turning points and other standout scenes have specific requirements, and there are certain elements that every Action or Reaction Section should have.

Laying out a plot using these strictures will probably suffocate the dedicated discovery writer (much the way Randy Ingermanson’s fractal-based and mostly helpful Snowflake Method has been known to do to unsuspecting pantsers) but don’t let this sway you from the value of the Marshall Plan when it is telescoped out from the scene by scene structuring. There is just as much valuable information in the Plan when it comes to the overall arc of your story, subplot, etc.

The Software

For those who enjoy the level of detail employed in the Marshall Plan, the software is probably going to be very appealing. I know that I personally jumped at the chance to review the program based simply on how much I adore the main book. I had expectations that this software would be on par with Scrivener or WriteWay Pro (both of which I have used over the years).

When I say “on par” let me spell out my expectation: a program that would help me organize key information, plan and outline my novel, and provide a native word processing function that would allow me to write the novel in sections tied to my outline. I get all of those and more with WriteWay Pro and Scrivener. (Much more in some cases) Those programs generally cost about $50.00, less when you catch a sale.

Now here’s the part where this review gets painfully honest.

The Marshall Plan Novel Writing Software fulfills all my novel planning and outlining needs, but lacks a function for writing and saving sections within the program itself, and also lacks a dedicated place to stow your research and scratch pad ideas. For so much less functionality than similar writing-based programs, you’d think this would cost a lot less than Scrivener or WriteWay Pro.

You’d be wrong. I checked for sales during NaNoWriMo and Christmas and again in mid-January. The current and constant price for this software has been $149.00.

Most aspiring writers just made their buying decision at the end of the last paragraph. But some of you are no doubt wondering “Is the part that’s there so awesome it makes it worth paying triple the money for 1/3 the functionality?”

What You Get For The Money

Again with the expectation/reality game. I thought, surely for that much money this will be one hell of a polished machine, a sleek German-engineered novel planning joyride. I mean, the sales literature even says, “It practically writes your novel for you!” and who wouldn’t want that kind of efficiency? No one, that’s who.

I searched for signs of that luxury app feel, some clue as to what would make this program worth that kind of scratch, and the only thing I can muster up as a reason is, as the cool kids say today: “because proprietary”. True to its promises, the software automates the difficult sectioning and outlining functions, in the specific proportions of The Marshall Plan. This would have otherwise been a laborious project, even if you had purchased the Workbook to help you. It also repeats key concepts from the books in scrollable windows of advice. Though the entire book is not included, just summary passages on structure, character building, editing, and careers. (To me they left the best part of the book out of the program, the parts covering techniques for clarity and how to handle exposition, dialogue, etc.) There is also an extensive list of Character Names and meanings.

Minor Complaints

The software feels unfinished to me for several small reasons, and one large one. The small ones first:

- There are numerous typos and artifacts of earlier builds hiding in the sparse help text and directions. For $150 this thing better be as typo-free as a query letter. Examples: 1) The text says click the Genre List above, but actually it’s a drop down menu on the left side of the screen. 2) “Or use a Reaction Section, as explained above” but the explanation is below. 3) There are an awful lot of doubled quotation marks “” scattered throughout the documentation.

- Arrowheads used to open and close parts of the program felt stingy and smallish; they required concentration to click them reliably.

- Minor Character support is not robust at all. You get to put in a Name and a Role, but if you want to keep any other info straight about them, you better go buy a notebook. Also, there does not appear to be a way to export Minor Character data.

- The List of Names is very long. Which would be just ducky if there was a search function, or you were allowed to jump to a certain letter. Nope. Start scrolling at A on either the Male list or the Female list. 7,000 names between them…

The Worst Offender

One of the earliest, and most important steps of planning your novel with this software is when you pick the overall length you are going to aim for. The program gives a lot of valuable information about averages for genres and so on, in perhaps a bit more granularity than that handy 2010 post from Colleen Lindsay’s The Swivet everyone likes to go by.

But where it gets dicey is when you decide on that length and then enter it into the form field directly under this, in red: “(Warning: Reducing your novel’s word length removes and/or resets sections, so data may be lost.)”

To be fair, the software does provide a warning. What does this mean in practice? It means that once you set a word length, the program will create a list of Action and Reaction Scenes and tell you which ones need to be from a certain viewpoint character and which you can choose the point of view. It will also dedicate space for you to write notes about what will happen in each of those sections.

But if in the course of writing—or even outlining—you discover that this is really panning out to be more of a 70K novel than the 90K novel you thought your idea would support, you have two choices:

- You can start a brand new outline file (because remember, this program doesn’t actually have a word processor built in) in the software and laboriously cut and paste all your notes for each section into the new outline file.

- You can change the existing file, knowing that you will lose what you have saved as notes for several sections. Print a copy before you change the length and then retype your notes back in.

To me, either option seems like a lot of wasted time that would be better spent writing that first draft. To me, this would be a dealkiller even if the program cost less than a Happy Meal.

Wrapup

I started evaluating this program from a very positive and hopeful place. I like The Marshall Plan books and I was excited about getting a copy of the software to try.

In the end, I wanted to give a better review than I was able to.

Until the software has more features, more polish, allows changing novel’s length without losing data, and doesn’t bite so deep into the wallet, I cannot recommend it for anyone without money to burn (a rare descriptor for novelists) and extraordinary confidence that they can make any story idea take X amount of words to tell it. There are just too many better values currently available in the marketplace, at a fraction of the cost.

That said, if you haven’t read The Marshall Plan for Writing Your Novel, I can’t recommend the book highly enough.

####

About the Reviewer: Lon Prater has worked in the Reactor Compartments of USS Enterprise, edited the military’s textbook on arms deals, and kept things safe in the produce and laundry industries. His fiction has appeared in the Stoker-winning anthology Borderlands 5, Origins Award finalist Frontier Cthulhu, and dozens of other publications. Visit www.LonPrater.com to find out more.

Most of my novel writing recently has been happening on the #86 commuter bus from Richmond to Montpelier and back. The wonderful thing about this is that when I ride, I almost always sit down and start writing immediately, no need for excuses or delays. Sometimes the writing is actual passages of the book, while sometimes it’s story notes, outlining, character exploration, and that kind of thing. Regardless, it’s always building the novel.

At the moment I’m moving scene by scene through a part of the book that is very emotionally draining. Yesterday I wrote a scene where one of my characters is screaming at another in the ruins of their apartment after a terrible tragedy. By the time the bus driver announced “Next stop: Richmond Park and Ride” and slowed down onto the exit ramp, I was practically shaking. I closed the laptop, shoved it in my backpack, and retrieved my lunch bag. As I silently went down the steps to exit the bus, the painful scene still echoing through my brain, and the driver said “Have a great night!”

Writing in public can just be emotionally weird.

Then I went home, where a rabid raccoon was hunched by our back door, near the clothes line. Our neighbors, a very nice couple who both come from farm families and for whom sick animals hold no novelty, had called the police, who in Williston I gather also are responsible for animal control. I first realized the police had arrived when I heard two sharp gunshots from the back yard. I went to the window and saw the officer and my neighbor chasing after the raccoon. It ran out into the middle of our yard, and the police officer shot it again, twice more. It stopped running, but flailed in place, clawing at the places it had been hit. By now, I believe, there were four bullets in the poor thing. After each shot, a faint spray of reddish brown had blown out just past the animal. Regardless, it was still moving.

At the time I thought about turning away, but I’ve gotten in the habit of facing things that scare me. (I’m much worse at facing things that inconvenience me, so I’ve got that to work on.) My son asked me later why I didn’t turn away, and I told him what I just told you. He was shocked and disturbed by it all, but later said he wished he had watched as well, even though I think it would have affected him even more than it did me. Ethan is looking at colleges where he can study animal science. He wants to get a graduate degree in Zoology and eventually work at a zoo.

I remember that back when my son and I volunteered at a raptor rescue center (birds, not dinosaurs) in nearby Shelburne, at first we both had a hard time with the chest freezers full of dead mice, chicks, and rats. We soon became acclimated to it, though, since we had to if we were going to feed the birds. Sometimes we even narrated what the rodents seemed to be saying, frozen in positions that resembled dancing, conversing, or casting an evil spell. I think that might have been a little too acclimated.

Anyway, the raccoon was still not dead. The police officer had to shoot it a fifth time, and again there was the spray in the grass behind it. It still moved, but it seemed weaker now. After another minute or two, it finally stopped moving. While they waited for it to die, my neighbor and the policeman laughed at something one of them had said. I thought about being offended, but the experience was no more novel for either of them than the frozen mice had been for me. At least they weren’t doing funny voices like we had done with the mice.

After the raccoon died, my neighbor got a pitchfork and a plastic bag to take care of the body.

There’s another reason I didn’t look away while the raccoon died, and I didn’t mention it to my son because I was a little embarrassed about it: it’s because I write. I can’t tell you how many deaths I’ve written, but it’s probably hundreds. Meanwhile, I’ve witnessed very few deaths, and I was aware that I might learn something from watching. I took note of the places where the animal looked like it had chewed out some of its fur, of the motions it made after being shot, of the sound of the gun, of how many bullets such a small animal seemed to be able to take. It’s a kind of recycling, taking in old experiences and creating new experiences from them. Does it honor the raccoon more to attentively watch its death and then write about it? Or is it taking advantage, trying to gain something from the animal’s painful and undignified end?

Of course, the raccoon’s real death started when it caught rabies. The policeman was just cutting things short before they got even worse for the creature, not to mention anyone or anything else it might come in contact with. And even if the raccoon knew I was watching, I seriously doubt it cared. Yet I take it as a reminder that writing is a serious business, even when the story is not a serious story. We’re shaping worlds and letting readers into them. What we do to our readers should have a point and a meaning and a purpose. When they come away from watching what it is we give them to see, they should have found a gift hidden in the narrative, something worth having no matter how painful or whimsical or unreal the events in the story may have been.

There’s so much meaningless suffering in the world, a little meaningful suffering-or joy-can go a long way.

In my current novel, my character names have been a mess. I’ve used up hours naming and renaming major characters, with the protagonist so far the most name-changed individual with two rounds of selection for her first name and three for her last name. Not only do I want each name to be right, I also want them to fit together, and to minimize the possibility of them being confused with each other. For instance, I generally try to avoid giving any two major characters of the same gender the first initial.

Naming characters well

Character names are important to me for a number of reasons. An awkward name makes it harder for me to read a story. A name with the wrong “feel” or associations is offputting. A name that I don’t like makes it hard for me to like the character. The wrong name in a story, especially in my own story, yanks me out of the experience and into a critical, peevish attitude that gets in the way of experiencing the story.

Some writers have nailed this. Shakespeare, for my money, was as poetic with his names as with everything else he wrote. Dickens was a master of names, too. J. K. Rowling has some of the cleverest names I’ve ever heard, given that she’s writing for a young audience. That she would have a wizard character with the intriguing but cheerful name “Tom Marvolo Riddle,” and that this would be an anagram for “I am Lord Voldemort,” with “Voldemort” not only having an ominous and terrible sound a la Sauron or Tash or (more subtly) Moriarty, but also having the meaning (if we apply German and French) of “full of death” … that’s just insane. I can’t imagine how she managed that.

Name resources

Let’s not set the bar too high, though. In terms of finding good, appropriate names for characters, first of all, here are a few of my favorite resources:

- The most common 1,000 U.S. surnames

- First names for boys and girls by nationality: 20,000 Names. Contains ads. There are a number of other baby naming sites like this.

- Most popular baby names for boys and girls by state, decade, year, etc. from U.S. Census

Scrivener (see “How Tools and Environment Make Work into Play, Part I: The Example of Scrivener” and “Would Scrivener Make You a Happier Writer?“) has a name generation feature which is very convenient, but I have often found these names to be too random and uncommon for my taste. However, it will let you choose nationalities and other factors, so for some Scrivener users, it might be just the thing.

Choosing a name: an example

Here’s a grid I used to choose a new surname for the protagonist of my current novel. I had five criteria:

- How the name sounded (to me) with the protagonist’s first name

- How it sounded with her family members’ first names

- How the name “felt” to me in terms of suiting this character (and to a much lesser extent, her family)

- Associations I thought readers might commonly have with the name, and

- Thematic resonance/appropriateness.

I got my list of candidates by browsing through that “1,000 most common surnames” link and choosing anything that looked like it might suit.

Check marks mean “win,” x’s mean “fail,” and tildes (~) mean “meh, sorta.”

In the end, I went with “Finch,” not only because it was the one choice to score all five check marks, but also because of the nuances of the the specific associations with advocacy, right action, long odds, great literature, and nature. What this gives me is a character name I feel good about and that works with me rather than against me. It doesn’t matter that I stole it: as Pablo Picasso once said, “Good artists copy, great artists steal.” Whether you steal your name or come by it honestly, here’s wishing you characters that sound like the people you want them to be.

Drawing by Irrisor-Immortalis.

I’m nearly through reading Roy Peter Clark’s book Writing Tools, which is proving tremendously useful in upping my writing game right now, and which may possibly be the best book on writing I’ve ever read in terms of both insights and practical application. The book is written to apply equally to most kinds of writing: fiction, journalism, memoir, blogging, etc.

One of the 50 writing tools Clark describes is entitled “Place gold coins along the path.” I realized on reading the section that this was something I greatly valued in writing and that I instinctively enjoy doing in my own, but I had never thought consciously of it as a technique. Having it laid out in this clear way makes it easier to understand where and how I should use it, for instance where I might want to stop and create a rewarding moment in a particular part of a story.

A gold coin is anything delightful to the reader. It can be a powerful line or quote, a delightfully witty exchange, an unexpected insight, a thrilling plot turn, a gorgeously-sketched setting, a moment of utter hilarity, or anything else that provides unexpected value or enjoyment. Whenever you’re reading and you get to a part that makes you say “Oh hell yeah,” that’s a gold coin.

Gold coins are a treat to the reader, a reward for reading that helps create trust, enjoyment, and commitment to the book or story. Clark recommends finding ways to include them regularly as the writing progresses, like gold coins dropped here and there along a forest path. He also points out that a reader who encounters a few of them early in a piece will begin to expect them to appear regularly-which is to say, to have confidence that the piece will be worth reading through to the end.

This helps me understand why I so often disagree with the advice “Murder your darlings.” When it applies to self-pleasing material that doesn’t do anything for the reader, darlingcide is great advice. When we’re talking about some little gem of a moment in the story that may not necessarily serve any standard purpose, such as building character, plot, or theme, it could be a doomed darling, or it could be a gold coin. If it’s not going to actively detract from the story and is something the reader might really enjoy, my thinking is that makes it a gold coin. Of course, the ideal is to offer gold coins that reward the reader and advance the piece.

Photo by Tjflex2

I’ve been researching and outlining my current novel for quite a while, but it was only this past week when I sat down to write the beginning of the book. Before doing that, I decided to try something intended to wake me up to what makes a good novel opening: I read through the beginnings of eight of the best novels I could think of-or more specifically, eight of the novels I was originally most engrossed by and continue to be most impressed by.

I didn’t worry about choosing my “eight favorites of all time,” and I strongly favored mainstream (that is, not romance, SF, Fantasy, mystery thriller, etc.) and adult over speculative and/or young adult (YA) because the novel I’m writing is a mainstream, adult novel. Otherwise I would have included The Lord of the Rings, The Golden Compass, The Amulet of Samarkand, The Hunger Games, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, etc.

By the way, except for Life of Pi (which I can’t recommend because I haven’t read it all the way through), I highly recommend any and all of these novels. To whatever extent your reading preferences are close to mine, I think you’ll love them.

My goal was to look for any specific tactics I would want to use in the opening of my own novel. I believe that beginnings are crucial, even more crucial than endings, because they signal what kind of book it will be and because readers often judge whether or not to read on from the first few pages or chapters. A bad ending may make the reader throw the book across the room, but a bad beginning will prevent the book from entering the room in the first place.

Of course, you can go back and redo your beginning any number of times, but as long as it’s not going to bog you down, why not start with your best effort? With that said, if you think it is likely to bog you down, this approach is probably no good for you. Some of us need more drive while others of us need more thought. I’m in the second camp.

The books I chose may or may not have been ideal for my purposes, since these books tend toward the “literary,” whatever that means when we’re talking about novel that were also commercially successful, and I’m trying to write a novel that offers a huge amount of real-life information in the form of an engrossing story, which is a bit of a different intention.

The results of my casual review were eye-opening for me. Here are the lessons I drew from the process, which may or may not be useful in your writing. I believe they apply in some measure not only to novels, but also to short fiction.

- I do seem to love me some first person POV, which is too bad, considering the book I’m working on, after sober reflection, should be in third person. It surprised me, though, that most of the books I chose as favorites were written in first person.

- All of the books gave a lot of information early on, but they varied enormously in what kind of information they gave and how pertinent it was to the story. Niffeneger gives a clear and understandable picture of a confusing and unusual condition (involuntary time travel) that is at the center of her story, for instance, whereas Martel drops a few vague hints of what his story is about and then starts spouting facts about tree sloths.

- All of these books implied or stated that something significant and terrible was going to happen but (possibly with the exception of Niffeneger’s book) didn’t go into the details of what that thing was for at least a little while. This ranged from the subtle (beginning the chapter by quoting a poem dealing with blood and destruction) to the extremely blunt (“I was fourteen when I was murdered on December 6, 1973.”).

- All used sharp and unusual metaphors and/or similes

- I hadn’t previously imagined this would be a key point, but all made highly opinionated observations and philosophical statements. Of course, this may be partly a product of the predominance of first person stories, but even so, I was struck by how outspoken the narration was.

- Most seemed to labor energetically early on (though not necessarily immediately) to explain anything that might be confusing or unusual about the story, but to do so in a way that seemed like a natural part of a story rather than stop-and-lecture. For example, Niffeneger demonstrates the time travel situation, Adams reveals that we’ll be reading a story about talking rabbits, and Stockett clearly depicts the structure of relationships in a household where a white woman hires a black woman to take care of her child.

- Something bad is happening or has already happened to the main character pretty much right away; we have a reason to sympathize and take that character’s side. This is different than the “significant and terrible” thing. It’s the difference between Harry being locked in a cupboard under the stairs (which wins our sympathy) and having to face Voldemort (which is the key conflict of the book).

- The first person narratives very often felt like being taken wholly into the person’s confidence right away: Holden Caulfield and Aibileen and Delores and all the rest feel like they’re telling all of their secret thoughts to the reader, implying a relationship of utter trust and confidence.

- All bring up large and meaningful issues right from the start

- Some of the books started with observations, reflection, and summary rather than diving right into a scene

Here are the raw notes I jotted down about each book as I went, in case you’re interested in the details I noticed.

Barbara Kingsolver, The Poisonwood Bible

· Immediately gives you reasons to both sympathize and be suspicious of the main characters

· Very “literary” in style, and first person, neither of which is well-suited to what I’m trying to do in my own book

· Surprising and gripping imagery

· Situation first, then explanation (not the other way around)

· Strong use of metaphor and vibrant description

· Brings up large issues (Africa, race, entitlement, guilt, privilege) in the first few pages

· Makes ethical/philosophical statements (“Most people have no earthly notion of the price of a snow-white conscience”) and controversial ones

· Strongly foreshadows

· Starts with reflection on everything (philosophy, metaphor, meaning, foreshadowing) and only then gets to the story of things

Audrey Niffeneger, The Time Traveler’s Wife

· Starts with personal reflection and immediate reference to danger and difficulty

· Ideas, philosophy, and generalization at beginning, not an immediate scene

· Startling premise given out in an incomplete way very soon

· Metaphor, simile

· First person again (still not applicable to what I’m doing, though)

· Second character introduced after only a few paragraphs, with vivid images of how time travel feels and specific examples that are half-summarized, half in-scene

· establish relationship immediately, in a meaningful way

· still a lot of reflection and summary in Henry’s part

· Beginning has an especially high proportion of effective poetics, sort of a demonstration of skill. Later in the book the descriptions and comparisons are still vivid, still lots of simile and metaphor, but the rest of the language is more transparent.

· The same is true in The Poisonwood Bible: later the story is still carried by metaphor and simile, but the intent is more narrative and less poetic and philosophical

J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

· Starts with character, giving us an immediate and clear idea of who this guy is and how he sees the world. We also get a lot of detail about his life-where he goes to school, what he values, what his parents are like from his point of view (in general terms), his brother, etc. Long first paragraph that kind of runs on. Voice dominates.

· Then fragments of scenes, mostly told in summary, that continue to illuminate what his life is like.

· First person again, of course. That just kills me, all that first person.

· There’s a palpable warmth and feeling of trust: you immediately start feeling like a confidant, that Holden might not be very reliable to most people, but for some reason he’s chosen you as someone with whom he’s going to be absolutely, 100% candid. The same thing at the very beginning of The Poisonwood Bible.

Richard Adams, Watership Down

· Title of the first part is “The Journey,” which foreshadows, and then there’s a quote from a Greek play about death and the stench of blood, so before you read even a word of the actual story, some tension has been created.

· Starts with a traditional kind of “lay of the land” description, with specific plant names and object names, the layout of things, and so on. It paints a pretty fair picture and only gradually focuses our attention on the rabbits. Once it does that, it starts by showing them as we would see them, then implies some personality, then begins to refer to rabbit culture in a way that technically could maybe still be considered realistic if it were based on zoology rather than sociology, and then finally crosses the line into explicit talking rabbit territory.

· He gives a character sketch of each rabbit in kind of a static way, but the tension he has built up for us tides us over durng this uneventful (though pertinent) material.

· Story picks up with a scene fairly soon, with several more reminders of something dire to come (probably more necessary because the scene is only rabbits out nibbling, though there is conflict early on with the pushy Owsla members). There is even foreshadowing in the footnotes.

· He establishes the “rules” of his world very early on and imparts a surprising amount of rabbit cultural information quickly. The omniscient voice helps with this, as do the footnotes. The style is traditional or even antiquated by modern American standards, but not far out of expectations and very suitable for the book’s original time and place.

Yann Martel, Life of Pi

Disclaimer: I haven’t read this entire book: I picked it based on reputation and the movie.

· Begins with broad statements that suggest great troubles but say nothing about them, and instead focus on the narrator’s academic studies. Quickly focuses on sloths, with interesting comments

Some broad and philosophical statements that suggest a wide scope of meaning for the story

· Goes on for quite a while about the habits of sloths, then meanders onto religion and science in an apparently undirected way-still not revealing why there would be any great woe in store

· Gets even more poetic and philosophical as it proceeds

· Descriptions are vivid, surprising, and opinionated, and imply larger parts of the story that are not stated outright, e.g. “… but I love Canada. It is a great country much too cold for good sense, inhabited by commpassionate, intelligent people with bad hairdos.”

Continues with hints and hints … who is Richard Parker? Why were you in a hospital in Mexico? What brought you to Canada? What story did the other patients in the hospital come over to hear from you? etc.

Chapter 2 is a single paragraph, an outward character sketch of the narrator.

· Chapter 3 launches into the narrator’s personal history. Clearly we will have to wait a long time before finding out about Richard Parker and what the story was that the patients came to hear.

Wally Lamb, She’s Come Undone

· Starts with a memory full of personal details and clearly marked as having unreliable parts. Fills in family details, personality, and how she was raised and treated. One scene, then another. First person again.

· By the end of the second scene, a broad reference to something very bad coming. Earlier on, hints that signing on with Mrs. Masicotte was a bad decision that will cost the family. Lots of period detail.

Kathryn Stockett, The Help

· Rotating first person POV again. Yikes, all this 1P!

· Establishes voice and role immediately, and the delivery clarifies that racial issues will be central fromm the first paragraph without anything about that being explicit.

· By the second paragraph, a situation and a scene are forming, with the white lady employer unable and possibly unwilling to take care of her child

· Narrator immediately focuses on the child’s needs, even though a screaming child is hard to care about, and earns our trust and admiration-and then she is very quickly effective in her role and we come to attribute competence and intelligence to her as well

· Metaphor, simile, and voice. “Her legs is so spindly, she look like she done growed em last week.”

· Some daring statements that begin sketching out the big issues the story will tackle. “I reckon that’s the risk you run, letting somebody else raise you chilluns.”

· Then begins filling in a little of her personal tragedy (her dead son), laying out the details of his death with all the clarity and candor of everything else she’s said.

· We feel here too that we are getting the full, frank story in a way that none of the other characters in the book will get it.

Alice Sebold, The Lovely Bones

· A one-paragraph preamble that’s both sweet and ominous. We don’t know it, but it foreshadows the whole situation of the book.

· Once again first person and voice and the extreme frankness.

· She dispassionately describes her murder in the second sentence.

· A few paragraphs later, makes the first reference to “my heaven”

· Spends some time sketching out a character who will have zero role in the novel but does have emotional impact.

· Occasional sharp and well-observed metaphors and similes

· Very soon launches into the scene in which she is killed. Wastes no time.

· However, interrupts it with personal reflections and thoughts about her family-as is appropos, considering it’s a book about Susie’s relationship with her family.

· Still in the interruption of that murder scene, a fragment of a scene in heaven, observing a scene on earth in which the murderer talks to Susie’s mother.

· Family observations and fragments of scenes in Susie’s heaven continue to be interspersed with the murder scene, as well as reflections on what she did and should have done.

Photo by Let Ideas Compete

Fellow Codexian and editor of the Unidentified Funny Objects anthologies Alex Shvartsman recently invited me to write a guest post for his blog at http://alexshvartsman.com/ . We talked about possible topics and came up with this question: what are the dangers and unusual opportunities of writing a novel that tries to convey non-fiction information as well? The resulting post was Really? A Novel With a Message?.

The original version of this article first appeared in my column “Brain Hacks for Writers” over at the online publication Futurismic. I’ve been editing and republishing each of my BHfW columns here. This is the final one, but you can read others by clicking here.

Writing a novel can be a little like a troubled romance.

Perhaps it started out with a flurry of excitement. Your idea swept you away and fascinated you–this was the one! This was the novel that was going to get finished … or be your first sale … or make a name for you. At the beginning, the characters were endearing or intriguing and the plot opened up before you like a twisty road opens up before a motorcycler on a crisp fall morning.

It’s Not You; It’s My Writing

Yet now … not so much. It’s not that you don’t still love your novel. Of course you love it! Except you also hate it. Writing it is no longer exciting: it’s work, and hard work at that. Worse, you begin to see the flaws in your original ideas and character conceptions, or you begin to worry that the whole thing is dull and unoriginal. You picture yourself plowing untold hours into the book and in the end having a manuscript that gets only contempt from agents and malignant disregard from publishers, or that you put on Amazon yourself and never sell except to your mother and her bridge partner. Ugh.

What happened? Well, of course it’s possible that you veered off the course at some point, that the scene that you thought would be so entertaining has undermined your character’s original appeal, or that you’ve resolved too many problems and now there’s no suspense, or whatever. In a way, though, it doesn’t matter whether the job is to continue writing the draft you have or to go back and rewrite part of it first: in both cases you have to actually sit down and work on the thing, and you are having all kinds of trouble forcing yourself to do that on a regular basis.

(If you never do have all kinds of trouble, of course, that’s wonderful, and this column is not written specifically for you. Congratulations, but please stop gloating.)

Passion, Not Judgment

There are two key questions here, one of which I’ll dig into and the other of which I’ll pretty much ignore.

The question I intend to ignore is whether the novel is good enough or not. That’s a topic in itself, and I’ve tackled it in a separate piece called “Your Opinion and Twenty-Five Cents: Judging Your Own Writing.”

The question I’ll dig into is this: if you’ve decided that you really do want to finish the book, how do you stop hating (or resenting, or avoiding) it?

Fortunately, the basic answer to this is simple: if you think things about the book that make you feel bad, you will have a hard time writing it. If you think things about the book that make you feel good, you’ll be likely to work harder, more often, and more energetically. You’ll also be likely to think about the project more, yielding better ideas, approaches, and insights.

For example, if I look at a novelette I’m collaborating on with a friend (yurt-living goat afficianado mom and talented writer Maya Lassiter) and think to myself “God, I am a jerk for taking so long to get those edits done,” then thinking about the novelette will consist mainly of me beating myself up for not working on the novelette, which will encourage me to avoid thinking about it so as to not feel so lousy.

If by contrast I think “I can’t wait for us to get that novelette sent out!” then I’m going to be much more excited to work on it.

Your Mental Firing Line

Is it really that simple? Yes and no. Sometimes negative thinking patterns are hard to break, and sometimes they’re extremely hard to break. (For help, see my articles on broken ideas and idea repair.) What’s more, we writers have a ridiculous number of things to worry about as we write: is it too long? Too short? Is the genre a good choice? How’s the style? Are the characters coming alive? Is it keeping the reader’s interest? Is it original enough? Is it so original that no one will know what to do with it? Are publishers buying this kind of thing right now? Are publishers even going to still be in business by the time I finish it?

If you want to finish the book, though, worry about those things only if it both helps the book and doesn’t make you want to go hide under the bed. If worrying about selling the book or about how good the book is prevents you from writing it, then assume it has a chance of being terrific and forge ahead.

Different people have different tolerance levels for this kind of thing, and the final measure is how a thought makes you feel. If you really need to get something done, then thoughts should be rounded up and forced to slave away making you happy so you can do it. Those who won’t go along with the plan of encouraging you to write your book should be lined up against the wall and shot. There will be plenty of time for their children, siblings, and friends to come after you seeking revenge later–when the book is finished.

photo by colemama