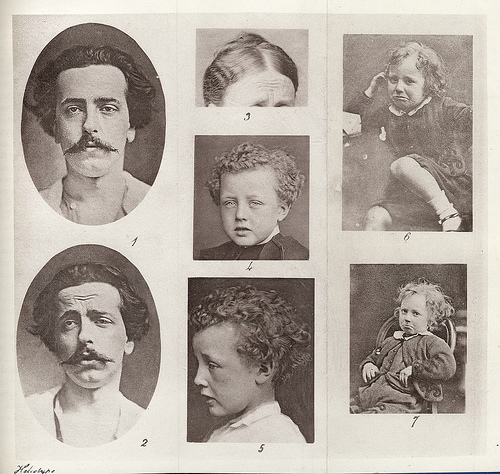

From Charles Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

How exactly do emotions work? From a scientific point of view the answers to this question are still in the works, but research over the last couple of decades has given us a much clearer sense of how they emerge. In her 2005 book Deeper Than Reason: Emotion and its Role in Literature, Music, and Art, Jenefer Robinson digs deep into various theories of emotions and into the neurological and psychological findings that can help us figure this question out and offers a model for understanding the important pieces. Her basic model, added to research and analysis from other sources, is what drives this post. There’s a lot of research still to be done, though, so consider the information here to be more of a glimpse at the best insights we currently have about emotion instead of something complete and set in stone. Even taking it tentatively, though, Robinson’s model gives us some seriously useful information.

The gut reaction

Emotions start (Robinson argues) with a gut reaction to something: a face, a sound, an idea, a conclusion, or even some change within our bodies. She calls these reactions “non-cognitive appraisals,” whereas I think for our purposes here, “gut reaction” works just as well, but it’s helpful to realize from that term that these reactions themselves aren’t anything we think through: they happen in hardly any time at all, automatically. That doesn’t mean the whole process of having an emotion is automatic, though, as we’ll see.

The high road and the low road

There are two paths our brain can take to get us to a gut reaction, the high road and the low road. The high road is about what you’d expect: we see or hear (or taste or feel or smell or think or remember) something, we figure out what it means to us, and then we react emotionally. For instance, while driving toward our house we might see blue lights up ahead, realize that they are probably coming from a police car, and begin to feel worried that something bad has happened.

The low road is a bit more surprising (unless you’ve read my post How to overcome specific fears and anxieties or another source with some of the same information): it still starts with some kind of sensory information, like a sight or sound, but in this case the amygdalae (a primitive part of the brain that we have on both the left and right side) flag it as something that has been associated with a powerful emotion or traumatic event in the past and sets off our gut emotional reaction before we even recognize what the thing is. For instance, if a person has been in an explosion caused by natural gas, the person may experience terror when smelling gas even before realizing that it’s a smell, or what the smell might be. Our brains seem to have evolved this trick of firing up emergency systems first and asking question later in order to help get us away from life-threatening situations as quickly as possible.

Even though the gut reaction is immediate and automatic, it can come down the high road as the result of thinking. For instance, I might spend hours going over my small business’s accounts before having the sudden realization that my accountant is stealing from me. As soon as I’ve had that realization, I’m likely to have a gut reaction (for instance of anger at the accountant, or fear of what will happen to my business, or happiness that I have found the reason for the cash flow problems, or even a combination) that’s automatic in the sense of reacting immediately to a thought that has been a long time coming.

Emotion is a process, not an unchanging state

But if we have that gut reaction, that doesn’t mean that we’re stuck in the corresponding emotion: instead, it seems to make the most sense to think about the emotion being a process that develops in several different ways at once, started by that gut reaction but subject to all kinds of changes. An emotion develops through:

- Body chemistry:An emotion will spur a physiological reaction through chemicals like dopamine (associated with pleasure), adrenaline (associated with fear and anger), seratonin (associated with serenity), oxytocin (associated with feelings of love), cortisol (associated with stress), and so on. These chemicals have a lot to do with the physical feelings emotions create, like butterflies in the stomach or a thrill of delight, and they also tend to sustain whatever emotion we’re having.

- Thinking (cognition): Once we start having an emotion, we tend to think about it and monitor our surroundings. For instance, we might see flashing blue lights and initially feel anxiety, thinking they’re from police cars, then round a corner and discover that they’re lights from a party a neighbor is having on their lawn.

- Body language: It won’t be news to you that happiness can make you smile and depression can make you slump, but it’s more surprising to realize that smiling can make you happy and slumping can make you more depressed. Fascinatingly, our own expressions, posture, and maybe even tone of voice can stimulate the same body chemistry that the corresponding emotion would create. Smiling can make us feel happier, and sitting up straight can help us feel more alert and positive.

- Being ready for action: Certain emotions tend to prime our bodies to be ready in certain ways: to focus our attention in a certain way or to be ready to move quickly. An example of this is flinching away at a sudden loud noise: our body is ready to act before we can even come up with a plan of how to act.

Different emotions at the same time?

These pieces of the emotional puzzle all go forward when we’re experiencing an emotion, and while they can work at the same time and in similar directions, they can also be out of synch or in conflict with each other. When that happens, they begin to influence each other, so that they tend to converge over time. For instance, if I am thinking something about something that makes me happy and my body is putting out oxytocin, but I decide to frown and turn my attention to things that upset me, the oxytocin will be cut off and replaced with other chemicals, my brain will conjure up memories of things that upset me, and my body will more and more begin to reflect the bad mood I’m creating.

It can be especially confusing to experience emotions that are out of synch. In the blue lights example, once I realize that it’s a party and not a crime scene, I may immediately feel intellectually better about the situation but still be feeling anxiety beneath that, because our thinking can change directions more quickly than our body chemistry. Fortunately, if we keep our thinking in the channel of the new emotion, our body chemistry will soon catch up.

Simple words for complex feelings

To make sense of emotions, we have a wide variety of labels for different ones, especially in English: terror, awe, euphoria, ennui, indignation, fury, and so on. When trying to reflect on how we’re feeling now or how we felt a while back, we tend to try to characterize our emotions to fit these available labels (although we also have emotion-charged memories that may give us more detail), and therefore tend to talk about emotions in a simpler way than we experience them. For instance, in the blue lights example, we might say “I was worried when I saw blue lights, but when I saw it was just a party, I was relieved.” This doesn’t capture that temporary conflict of thinking and body chemistry, nor the subtle details–perhaps the initial worry was mixed with indignation that a crime was happening in our neighborhood or guilt at something we ourselves had done; maybe the relief that the blue lights meant just a party was mixed at different times with irritation at the likely amount of noise, excitement that we might be invited to the party, and/or surprise that the neighbors thought blue lights were decorative. To put it another way, our emotions are not simple, exclusive states, but instead an evolving process that can include parallel and conflicting pieces that are hard to easily summarize in words. Fortunately, we have poets, artists, musicians, and others to help us communicate about emotions without resorting to simple summaries.

How idea repair can help drive emotion

A last note: in posts on idea repair, I’ve talked about thinking causing emotions. In light of this article, that idea may seem oversimplified, but to put things in perspective, idea repair is the process of thinking and directing attention that begins immediately after we have that initial gut reaction. Idea repair can’t directly affect the gut reaction (although over time it might train habits that will change initial reactions), but modifying our thinking is probably the most powerful single thing we can do to turn an emotion in a positive direction once an emotional process begins.

Police lights photo by Sven Cipido.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Psychologist Daniel Goleman’s book Emotional Intelligence may be 15 years old, but the ideas and information in it, far from being out of date, are being confirmed and expanded in psychological research to an extent that might be surprising even Goleman.

Psychologist Daniel Goleman’s book Emotional Intelligence may be 15 years old, but the ideas and information in it, far from being out of date, are being confirmed and expanded in psychological research to an extent that might be surprising even Goleman.

Fitness instructor Matt O’Brien runs

Fitness instructor Matt O’Brien runs  Writer Amy Fries posts information about harnessing daydreams for visualization and creativity on her blog

Writer Amy Fries posts information about harnessing daydreams for visualization and creativity on her blog