The way some of us writers talk, you’d think agents, editors, and publishers were celestial beings who descend from the firmament at whim to generously bestow grace (in the form of a publishing contract or literary representation) on us undeserving, lumpen creatures.

The way other writers talk, agents and publishers are scam artists and parasites who feed off the blood, sweat, and money produced by writers.

So what are we to think?

Who’s in charge?

When I frame the two perspectives that way, you can probably tell I don’t really subscribe to either extreme. Literary representation ought to be conducted as an equal relationship. Here’s some of my discussion on the subject as responses to concerns I’ve heard about agents.

“It’s the author’s money”

Have you ever run a business? If so, reflect on how money came in: there will have been production (rendering the service, manufacturing the widgets, building the furniture, or what have you) as well as sales, billing, and support.

In an author-agent-publisher relationship, the author supplies the product, but a good agent sells that product to the publisher, negotiates (we hope) an appropriate deal, collects the money, keeps on the publisher to make good on commitments, etc. While it is possible for authors to sell their own books, when the author works with the agent the agent is generally doing the selling, and many authors cannot sell to big publishers without an agent. As such, the author producing the book doesn’t amount to a pile of poo, monetarily speaking, unless the agent sells it or unless the author takes on the agent’s job and sells it.

Production without sales and related services is worthless unless you have a business where your products automatically sell themselves, e.g., you inherit some kind of monopoly.

“The agent chooses the author” – or – “The author chooses the agent”

The author and agent choose each other. Can I go up to Agent X and say “You will now be my agent!”? (Well, of course I can, but I mean the average writer.) No. Nor can the agent come up to me and say “You will now be my client!” (Although admittedly, that’s more likely to work.)

This is what I mean by a mutual business arrangement. Neither party is forced into the arrangement and neither party has sole say in what happens.

“Agents used to get only 10%: why is the norm now 15%?”

When talking to a very successful writer in 2001, I was advised to only ever sign with an agent who made 10% for domestic sales (the percentage is generally a bit higher for foreign sales), but even that far back, almost all agents had already gone to 15% for new contracts: the famous author in question had gotten an agent in an earlier and different publishing environment.

My guess is that the change in percentage is because the real value paid by publishers for books (taking into account inflation) went down and agents couldn’t make a living otherwise. For instance, advances for first science fiction and fantasy novels appear to have been more or less flat from about the 80’s through now from what I’ve read (though some of the information going into that statement is anecdotal, so take it with a grain of salt).

If good agents were able to survive on 10%, those good agents would have snagged all the good writers and left none for the 15-percenters, most likely, and though I admit that collusion and other methods could conceivably get around this, I don’t really believe anything like that happened.

My guess at why the value publishers pay for books went down is the rise of word processing: it became easier and faster to produce books, so publishers had more producers and product to choose from and had to spend more time sifting through submissions. If we want to point the finger at one factor that has lessened the power of individual writers in recent decades, the word processor is probably it. And yet, ironically, the word processor has also made us each much more powerful. Ah, the contradictions of technology!

“Agents have become irrelevant”

My personal sense is that agents will continue to be relevant to the extent that big publishing house tradpub continues to be relevant, and while I don’t see tradpub holding onto its dominance in the long term, I also don’t expect big publishing houses to die off entirely, so I think agents will be likely to still have a role. That said, selfpub seems to be taking an ever-growing slice of the pie, and agents are useless for that, so I sure as heck would not want to be starting a career as an agent right now.

It does seem to me that writers often have the habit of giving up their perception of power to agents and publishers when the writers’ work is what the whole publishing industry is founded on and the only particular thing it can’t do without. At the same time, I think it’s misleading to imagine that either party has all the power in an agent-writer (or writer-agent) relationship, or for us writers to imagine that the world revolves around only us.

The power approach

Codexian Jake Kerr has a different perspective on the matter that I think is also worth hearing. He says:

[It’s about] who has more power in the relationship. When you first start out as a writer, odds are that any agent looking at you sees you as a POTENTIAL moneywinner. How much of one depends on their confidence and your track record. In this scenario, I am sure they see you as little more than a calculated risk, and thus playing the “you work for me” card is somewhat foolish. You have no juice.

This changes dramatically as the money flows in. Then the reality is that the author has all the juice, and the agent really IS your employee. The more money = the more power you have over both your agent and your publisher.

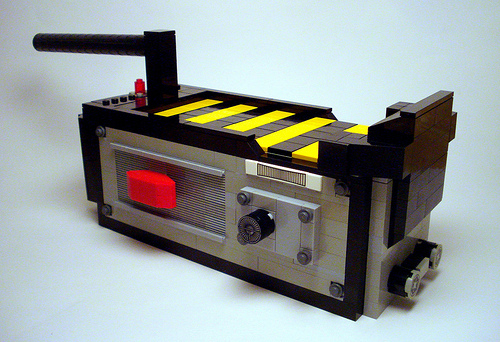

Cartoon courtesy of Bificus