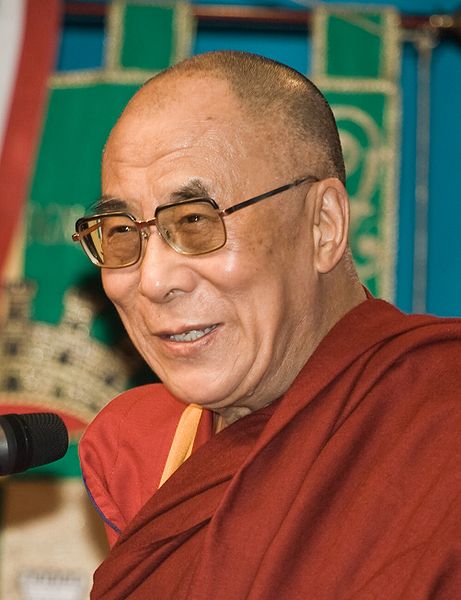

In recent posts like “3 Keys to Living Effectively: Attention, Calmness, and Understanding” and “You, Me, and the Dalai Lama” I’ve talked about some of the things I’ve been learning and contemplating from listening to recorded talks by the 14th Dalai Lama after having the good fortune to see him speak in person last month. At the end of his talks, he generally takes questions, and one of the questions that seems to come up pretty frequently is how to forgive someone who won’t admit they’ve done wrong.

When relationships in our life are disrupted or hurt through some past or present trouble, it can be a constant drain. In some cases the problem can be solved-or at least mostly solved-by cutting ties: friends who mistreat or lie to us, for instance, are sometimes not friends worth having, at least not if we’re trying to lift ourselves up by keeping company with people we admire.

In many cases, though, cutting ties is either not an option or too drastic an option, for instance when immediate family members do something (or a lot of things) that we find harmful. Even when it’s possible to stop communicating with a family member, the problem can still fester, and of course cutting off a family member creates its own problems.

So another avenue is to have a heart-to-heart discussion with the person who has done the harmful thing to try to understand and forgive. Of course this approach is a big improvement on simply cutting ties, and it’s likely to bring more peace. But what if the other person doesn’t want to be forgiven? What if the other person doesn’t even agree that there was any wrongdoing? For that matter, what if the person keeps doing the harmful thing?

A situation like this begins to make it clear what real compassion and forgiveness are. For us to feel compassion or forgiveness toward another person, that person doesn’t have to act according to our preferences or beliefs, because there is a difference between the person and the action. We can and should condemn actions that we think are harmful or unjust, but even while doing that we can accept and feel compassion toward that person. We can even feel compassion toward people we oppose.

I admit, this isn’t an easy thing to do, but at least the steps are clear. All we have to do is say “I condemn what you’ve done, but I support you“-and mean it.

There’s another piece of this, an important one: forgiveness and peace of mind are matters that happen within ourselves, not outside us. If we want peace of mind, we have to take complete responsibility for it ourselves. If we let even a small part of our peace of mind depend on what other people do, then we open ourselves to being disturbed and angered and made unable to act and think as we wish based on things other people do, things outside of our control.

In the same way that we can release anger that might come up from, say, getting cut off in traffic by reminding ourselves “I can’t make other people drive the way I want them to,” letting go of any feeling of possession about other people’s wrongdoings is necessary to feel peace of mind in troubled relationships and to offer compassion and support even to people whose actions we condemn.

Photo by h.koppdelaney

The room was kind of a large one-actually, an arena. The Dalai Lama was speaking at the Nelson Recreational Center in Middlebury last Saturday. I sat about 60 feet away, close enough to exercise my dazzling photography skills and get this fuzzy phone cam shot you see to the left. If you’d like to watch the event for yourself, there’s good video footage of the whole thing

The room was kind of a large one-actually, an arena. The Dalai Lama was speaking at the Nelson Recreational Center in Middlebury last Saturday. I sat about 60 feet away, close enough to exercise my dazzling photography skills and get this fuzzy phone cam shot you see to the left. If you’d like to watch the event for yourself, there’s good video footage of the whole thing