This is the fourth interview and the sixth post in my series on inclusivity and exclusivity in fiction. You can find a full list of other posts so far at the end of this piece.

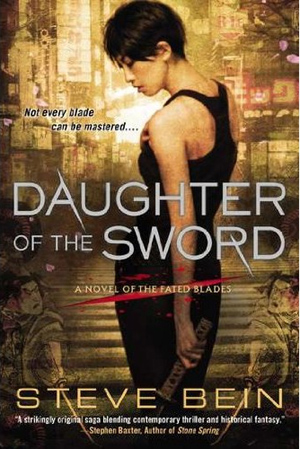

Today’s interview brings in Steve Bein, an award-winning writer of science fiction and fantasy whose new novel series from Roc, The Fated Blades, features a female police detective working in Tokyo.

LUC: In your novel Daughter of the Sword (due out from Roc October 2nd), your main character is a Japanese woman, and one who’s trying to make her way in what in her world is an extremely male-dominated profession. She’s hardly the first Japanese character to emerge from your pen, either. What brought you to write about a character so different from yourself? Was it something the story demanded, or did the story emerge from wanting to write about such a character?

STEVE: I’m very interested in questions of alterity and alienation, and so a lot of my protagonists don’t feel at home in their worlds. Mariko is one such case. I think one reason I’m so interested in this kind of character is that in many important respects I rarely feel at home myself. Alienating and ostracizing my protagonists allows me to sympathize with them, and I think a lot of readers also sympathize with a character who feels out of place, especially when that character is cast out unfairly.

On the other question, the story demands a Mariko, or at least a protagonist that is Mariko-like. She needs to be in a position to investigate crimes linked to a medieval sword (no spoiler there; the flap copy reveals as much) and she needs to be female (and to reveal why would be a spoiler, so I ain’t tellin’). Once that much was clear, then I got to think a lot about how to sharpen her difficulties, to alienate her further, and what that would do to her character, and how that might initiate feedback loops (i.e. the ostracized reacts to being rejected and that reaction prompts greater rejection). But of course the fact that she really had to be so different from me posed huge challenges in the writing itself. She’s by far the hardest character for me to write.

LUC: What are the specific challenges of writing Mariko, and how did you try to address them?

STEVE: There are two big challenges with writing Mariko, the first having to do with story structure and the second having to do with the fact that she’s a Japanese woman and I’m not.

This novel follows three of the greatest swords ever forged as they exert their influence over about a thousand years of Japanese history. Mariko gets about half of the book, and the other half takes us to different periods in Japanese history, where we see the swords in the hands of samurai warriors WWII officers (and ninja too, if you read the companion novella, Only a Shadow). Each of those stories is a brick in the wall, and Mariko’s story is both brick and mortar: her story has to hold together on its own and it has to tie all the other stories together in one cohesive arc. So one reason she’s tough to write is because her story has so much work to do.

The other big difficulty in writing her is the fact that she’s the only female protagonist in the book. She’s the most important protagonist in the book, but all the rest are guys. I’m sure the women in my life will be happy to tell you that I don’t really understand women. Obviously it’s a mistake to speak of “women” as if they all think alike, feel alike, etc., but nevertheless I think male blindness is a reality and I think women perceive and react to and live with social realities that a lot of men never notice. It takes a lot of thought, a lot of observation, and a lot of rewriting to get a female protagonist to feel female.

LUC: What are the dangers of getting a character of a different ethnicity, background, gender, and profession wrong?

STEVE: You don’t want to get Japanese culture wrong, out of respect for the culture and also because the anime rage is now twenty-odd years old, and that means there’s a huge number of Japanophiles out there who are very likely to catch any mistakes you make. Japanese culture is easy to caricaturize–easier than most, I’d say–and so it’s all too easy to go from a thoughtful book to a chop-socky flick just by inattention to details and nuance.

I’ve lived in Japan, I’ve taken students there, and I’ve spent a lot of time indulging my fascination with Japanese culture, so all of that mitigates (and I say mitigates, not eliminates) the danger of getting the culture wrong. Getting police culture wrong is a different story altogether. The lingo is different, the attitudes are different, the political climate is different. Of course you literally wrote the book on subculture slang, so you know about that aspect of it, but it’s more than language. One of my closest friends became a cop, and it’s been very interesting to observe what it’s done to his psyche. He just doesn’t look at society the same way anymore. He’s seen the seamy underbelly, and I think trust and brotherly love just don’t come easily to a person after that. I’ve interviewed a lot of cops for this book, especially female cops, to get other perspectives on the profession. I think writers have to do that sort of thing if they really want to get the details right.

But that raises the other danger, which is getting so enmeshed in the details that no one but an expert can read your book. I’m constantly thinking about the sorts of things you can say in English that you just can’t say in Japanese, and sometimes that can get in the way. For example, in the next book I refer to a character’s face as “cherubic.” Cherubs are of Mediterranean origin, so no Japanese guy in the 1500s could describe someone as cherubic. But go too far down that road and you’ve got to write the book in Japanese. Maybe I’ll change the cherub reference and maybe I won’t, but at the end of the day what flows best with the sentence is more important than what’s 100% authentic.

LUC: What approaches to inclusion and exclusion do you expect to take in your fiction going forward?

LUC: What approaches to inclusion and exclusion do you expect to take in your fiction going forward?

STEVE: I don’t really care for the language of “inclusion and exclusion.” It’s not as if I deliberately exclude any particular category of people in my fiction. There are lots of genres I have no interest in, but I can’t say the same of characters.

That said, I buy the old maxim that good fiction is interesting characters in difficulty, and the characters that interest me tend not to be straight white able-bodied men. I have no idea why this is true. I only look at my body of work so far, and my protagonists include a straight white cabbie, a straight white physics student, a Tibetan astronaut, a Kenyan astronaut, a Japanese secret agent, an intelligent computer, a teenager who lost her arm in an accident, a samurai boy born with a lame leg, a blind and elderly professor, and Mariko, a Japanese cop who spent a lot of her childhood in the States and is alienated because of it.

A couple of early readers of Daughter of the Sword have assumed Mariko is a lesbian. I don’t give her a boyfriend or a girlfriend in the book — she’s far too busy to have a dating life — so I assume this must be people unconsciously applying the meme that tough female cops are lesbians. You certainly see a lot of that in police stories, but I don’t like subscribing to tropes like that. I would say that if I wanted to make Mariko a lesbian, I’d have to go through the manuscript again, examining all of her scenes, all of her internal monologue, and see what assumptions I should and shouldn’t be making about her view on the world. I’d want to figure out what kind of women she’s attracted to, and revisit her relationship with her parents and her sister — all kinds of stuff. The actual changes to the manuscript might be few and far between, but they’d be important

So going forward, I don’t anticipate much change in the types of characters I find interesting. Whoever they are, I feel like the writer’s job is to get in their heads, figure out what they’re sensitive to, what they’re blind to, how the world looks different to them than it might have looked from another perspective. It can be small stuff. I’ve got two aging dogs and all of a sudden references to dying pets are cropping up all around me. They were always there; I just wasn’t sensitive to them before. Mariko has her own cues, her own pet peeves. Every character will have them if you explore deeply enough.

LUC: What kinds of inclusivity or alterity would you like to be able to find more of, as a reader?

STEVE: I like aliens that are actually alien. I don’t mean anatomically, I mean psychologically, emotionally, relationally. China Mieville’s Ariekei in Embassytown or the buggers in Card’s Ender’s Game novels are a lot more interesting to me than Star Trek aliens who are just like us apart from the little knobby things on their heads.

I’d like to see more fantasy stories that start from somewhere other than the generically European backdrop that’s almost universal these days. (I shouldn’t even say “these days.” I don’t know of a time when this wasn’t a basic assumption of the genre.) As it is now, you’re almost required to write fantasy this way. I had an editor reject a story because the protagonist had tan skin and a bow and wasn’t Native American. She didn’t entertain the possibility that fantasy worlds could be populated with human beings that don’t fit neatly into any of our racial and cultural assumptions. In fact, the opposite view is arguably the better one: those assumptions of ours are ours, and different histories would necessarily generate new sets of assumptions.

Posts so far in this series

- 7/27 – interview with Leah Bobet

- 7/29 – Where Are the Female Villains?

- 8/3 – interview with Vylar Kaftan

- 8/9 – Concerns and Obstacles (multiple mini-interviews)

- 8/10 – James Beamon on Elf-Bashing