It’s true that relationships with other people are not at the center of habit formation: habits form within our individual brains. Yet our relationships with others still influence how our habits form in a huge number of ways: other people can

It’s true that relationships with other people are not at the center of habit formation: habits form within our individual brains. Yet our relationships with others still influence how our habits form in a huge number of ways: other people can

- support or undermine our efforts

- provide a positive or negative example

- distract us

- buddy up with us, making habit formation easier

- be part of the habit we’re trying to change (for instance, if the habit in question is about how we treat others)

- provide vital information or training, as with a mentor

- affect our mood through interactions

- affect our overall happiness based on how healthy our social connections are

- and so on.

With that in mind, it appears likely that any significant improvements to our relationships with others will tend to aid us in forming habits we want, breaking habits we don’t want, and reaching goals.

To that end, I’d like to pass on a metaphor from Stephen Covey, author of The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. While Covey’s book isn’t particularly research-based, he provides what seems to me a useful take on how we approach our lives. Covey’s metaphor is this: trust, an essential basis for constructive relationships, is like a bank account. Says Covey,

An Emotional Bank Account is a metaphor that describes the amount of trust that’s been built up in a relationship. It’s the feeling of safeness you have with another human being.

If I make deposits into an Emotional Bank Account with you through courtesy, kindness, honesty, and keeping my commitments to you, I build up a reserve. Your trust toward me becomes higher, and I can call upon that trust many times if I need to. I can even make mistakes and that trust level, that emotional reserve, will compensate for it.

Part of the utility of this idea, for me, is in offering a simple approach to getting inside someone else’s point of view in a relationship. If someone else is behaving toward me in a way I don’t like, for instance, there’s a good chance that there’s a trust problem between us. What has my interaction been with this person? Have I given them reasons to trust me and be glad I exist?

Of course relationships are a two-way street, and we can’t always rely on other people to take note of the deposits we’re making, but since we can’t control other people’s thoughts or actions (one reason why worrying about how things “should” be can be so emotionally destructive for us), one of the most empowering things to do in relationships is to try to gauge our current emotional bank balance. Is there a good fund of trust stored up in that account? Or are a few healthy deposits needed to prevent overdrafts?

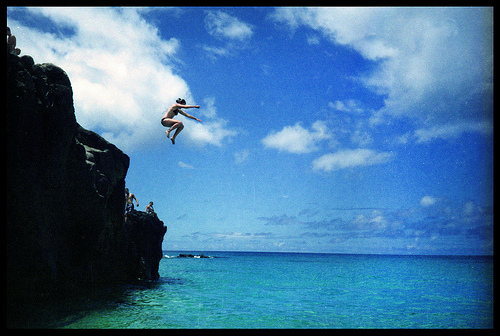

Photo by Andy on Flickr