I started this blog about four and a half years ago and started doing energetic research into willpower and habit change two years before that. My belief when I started was that it would be possible to learn how to change nearly any habit, to summon far greater willpower, because it was clear that around the world, there are people who make these changes every day. So, is it true? Does learning about habits and willpower give you willpower and mastery of your habits? The answer is no … and yes.

The further I got into this subject, the more I kept wondering when I would break through. I lost weight, got much more fit, earned a black belt, finished writing books, eliminated some bad habits, improved my relationships, and otherwise made a lot of improvements in my life … but I would still sometimes waste time I needed for more important things, show up late now and then, make bad decisions, or otherwise demonstrate to myself that whatever willpower was, I hadn’t mastered it.

So I sat down the other day and pondered everything I’ve learned since 2007 or so. If learning all about habits and willpower doesn’t give you mastery over them, what does? As near as I can figure it, it comes down to four things that stand between us and change. I think when I describe them, you’ll see why learning alone doesn’t cover it (other than the facts that habit change takes time and that just knowing about something won’t automatically change our behavior).

1. Tools and Knowledge

Here’s an area where what I’ve learned and written about here has been powerful. Mental and emotional tools can cut through a lot of habit difficulties and get us on the right path. For example, we can learn to generate confidence and enthusiasm in place of depression and hopelessness with idea repair; we can clear our minds and let go of things that bother us through meditation; and understanding mental schemas can let us get to some of the root causes of our worst behaviors.

2. Thinking

How we think, what we tell ourselves, and where we put our focus make a huge difference in how we feel and what our lives are like. We can often change our thinking using tools like the ones I mentioned, but whether it occurs naturally or has help through mental tools, our thinking itself is crucial in determining our actions and decisions.

3. Lifestyle

Nutrition, sleep, exercise, friends, social contacts, activity, surroundings, physical tools, responsibilities, family, and many more external factors can influence our internal state. Here too, I’ve learned about many useful improvements through researching and writing about the psychology of habits on this blog, whether it’s a quiet walk in green space, having just the right tool, or keeping company with people who help us become better.

4. Commitment

Here’s the tough one: we have to care. Knowing how to do something or having a theoretical goal generally doesn’t carry us very far unless we’re strongly and consistently motivated by our own emotions.

I’m not just using “commitment” as a substitute for “willpower” here, creating a circular argument. What I’m talking about isn’t making the right decisions or doing the right things, but rather consistently caring about our decisions and what the right ones are.

Commitment can come from many different places, so fortunately we can influence it. It can come from our own emotional difficulties: for instance, a person who craves attention might use that to drive excellence in music, or a person who hates conflict may learn how to be a consummate peacemaker. It can come from thinking and understanding, when we get to know ourselves better and make important connections. (It’s one thing for me to know that doughnuts aren’t good for me, but it helps me more to realize how foods like that contribute to atherosclerosis, drain my energy, and give me a headache). It can be inspired by a role model or a clear picture of the future, be shocked into us through a tragedy, be nurtured by helpful surroundings, or rest on support from friends and family. Commitment is an emotional state in which we yearn toward a goal or state of being. Without it, it doesn’t matter how we can act, because commitment directs how we do act.

Which matters … why?

The point of bringing up these four aspects of willpower or habit change is to create a simple way to look at our goals and see what’s missing.

For example, why did I lose 60 pounds or so and then stop about 15 pounds heavier than my ideal weight? After all, I have the mental tools to lose weight and know how to direct my thinking, and my lifestyle is compatible with fitness and weight loss. What happened, I believe, is that my commitment dried up. Having reached this point, I’m fairly happy (though not ecstatic) with how fit I am, and my health is very good. Losing more weight would make me look better, which would be a fine thing both in terms of my self-image and my romantic relationship, but there’s nothing about it that would affect my life expectancy or my ability to be in my relationship in the first place, whereas my old weight years ago really could affect those kinds of things. To lose more weight, I’d have to find reasons to really, really care. This might involve hanging around with extremely fit people, finding more reasons to lose the extra pounds, or working on increasing my enjoyment of fitness.

In the same way, any of the four things above can be missing in a person’s quest to change. For example, a person might passionately want to quit smoking, might live in an environment that discourages smoking, and might be beautifully focused on the problem, but if that person doesn’t have a good working approach-that is, doesn’t have the right tools-then quitting may fail time and time again.

So I invite you to do in your life what I’m doing in mine these days: if you have an important goal that you’re having trouble reaching, look at it in terms of these four factors. Do you have all the tools and knowledge you need to succeed? Are you thinking thoughts that move you toward your goal? Is your environment helping or hurting you (or both)? Are you deeply and emotionally commited, and does that commitment stay strong even when trouble comes?

So, will I ever master willpower and habits? Somehow I suspect not, but it continues to be worth trying, and I continue to push hard. Maybe in another six and a half years. Who knows? It could happen. Check back with me then.

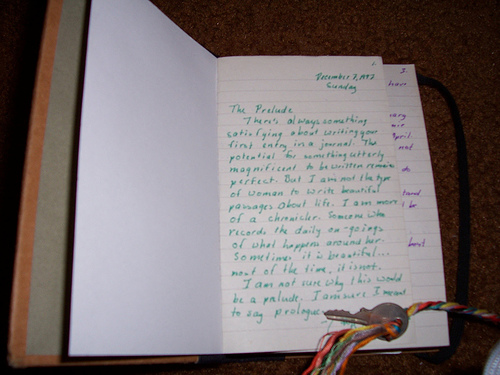

Photo by foxypar4