This is the eighth interview and the tenth post in my series on inclusivity and exclusivity in fiction. You can find a full list of other posts so far in the series at the end of this piece.

In today’s post, I talk with Russian-American writer and physician Anatoly Belilovsky.

LUC: Your background and origins are very different from most English-speaking writers and readers. How does that affect how you read and write fiction?

ANATOLY: That used to be an easy question, until I found at least three other Anglophone writers with backgrounds somewhat similar to mine, whose writing and criticism of science fiction and fantasy (and much of everything else) is either different from mine, to varying degrees, or, in one case (and, no, I won’t drop names here) diametrically opposite. So, in a broad sense, I am not sure how my origins feed into my weltanschauung. I think the best I can do is tell my story and let readers make their own conclusions.

I grew up in a culture whose dominant language has no words for privacy and appointment, with an entire set rules of etiquette for behaving while on a queue, with another set of traditions for communal apartments with shared kitchens and bathrooms; a society in which, for most of its history, its own government, while pretending to look out for the good of the common people, committed unparalleled atrocities against them.

It was also a culture that took art and literature seriously - as serious tools for social engineering. “Inclusion” and “marginalization” had very different meanings there and then: “Inclusion” meant membership in Writer’s Union, which opened doors to publication, and “marginalization” meant being relegated to Samizdat (“Self-publishing,” a tricky proposition in a country in which typewriters were registered with samples of output to permit matching pages to their sources) or Tamizdat (“There-publishing,” by Russian emigre markets - the route that led to highly embarrassing Nobel Prizes in literature for Joseph Brodsky and Boris Pasternak, for works never published in their native country.) The Writer’s Union also took seriously the question of publishing underrepresented populations: having praises of Worker’s Paradise sung by a variety of voices in a variety of languages was a major priority. This led to a highly amusing episode: two banned writers encountered an unknown aspiring poet who was bilingual in Russian and another, obscure, language. Forming a mini-conspiracy, the trio wrote ideologically impeccable poetry that brought in money and prizes by the bucketful, and continued to circulate what they wanted in Samizdat.

Outside of the never-never land of inter-ethnic harmony in Social Realist literature, things weren’t all that rosy:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deportation_of_Koreans_in_the_Soviet_Union

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volga_Germans

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deportation_of_the_Crimean_Tatars

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Night_of_the_Murdered_Poets

To make a long story short, coming to America was a culture shock of which I’ll talk in another installment. Suffice it to say that, right from the start, much of what would be considered a dark dystopia by a Western reader, felt like a lighthearted satire of the real world (A Clockwork Orange, 1984.)

As for “literary” fiction, I never could bring myself to care for most of its characters and conflicts. Catcher in the Rye is emblematic of that: I’m afraid I never could see Holden Caulfield as anything other than a spoiled brat in search of excuses for his upper-class ennui.

LUC: What kinds of issues about inclusivity or disregard do you see in other people’s fiction that the authors themselves often miss?

ANATOLY:

I have a black, a woman, two Jews and a cripple. And we have talent.

-James Watt

If you prick us, do we not bleed?

If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us,

do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?

If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that.

-William Shakespeare

Pound pastrami, can kraut, six bagels—bring home for Emma.

-Walter Miller Jr

I chose these quotes to illustrate a few points.

The second is to illustrate what inclusivity is, all too often, exclusively defined as: writing about characters whose “differentness,” and society’s callousness in dealing with that “differentness,” is the sole, or the major, driving force behind the plot and the character’s actions. That’s a perfectly valid way of looking at inclusivity, but it really isn’t mine. I look for common ground, for the universal experience.The first one is to illustrate what inclusivity isn’t. Hogwarts inclusion of the Patel twins and Cho Chang cannot be called inclusive: the twins’ roles rise barely above those of furniture, and Cho gets to break under pressure and then feel terrible about it. If plot is a river, Cho gets swept away by the current while the twins get to sit on the banks and stare at the water. Whatever roles were given to individuals who shared the panel with Mr Watt, they were clearly not the ones who rowed that boat.

Which brings me to the third quote. It bears repeating:

Pound pastrami, can kraut, six bagels—bring home for Emma.

Miller is writing about a Jew - never mind what happened to that Jew later, he’s certainly a Jew writing these words - who is thinking what anyone would be thinking, with apocalypse looming beyond the horizon: he is thinking of his family.. And instead of drawing a huge red arrow that says, “LOOK AT ME - A JEWISH MENSCH WHO LOVES HIS FAMILY!” he is keeping that feeling in the subconscious, the tip of the iceberg of genuine powerful love showing up as a note to self to bring home some food. Leibowitz’s Yiddishkheit quite literally shows up in the grammatic construction (of is superfluous in languages that have a genitive case) and in the food choices, the limbs and outward flourishes, while his universal, transcendent Menschkheit (which I choose to translate as “humanity,” not “masculinity”) is responsible for the caring that drove it.

Now I get to talk about my kind of inclusivity.

Ken Liu’s Nebula and Hugo-winning Paper Menagerie [note from Luc: between when we conducted this interview and now, the story also won the World Fantasy Award] is about a kid who’s ashamed of how uncool his mother is. OK, the kid is half-Chinese and his mother barely speaks English, and the descriptions are good enough that you find yourself totally immersed in the story, you can see the scenes and the characters as vividly as if they were on film, and yet it brought up memories of my late, decidedly non-Asian mother, and the catharsis of the story’s protagonist triggered one of my own. I had a conversation with Ken about that story at Readercon, and I think it surprised him, at least a little, how broad an appeal this story had.

On the same Hugo ballot was Mike Resnick’s Homecoming. It’s a universal “fathers and sons” story, relevant to anyone, and here is the funny part: I first heard it as a podcast, narrated by an African-American voice talent. I could see the characters of this story as well, in my mind’s eye, and the father came across as a very definitely African-American elderly man. Didn’t change the universality of the story, only grounded it in a very specific mental image. And I really don’t know if I would have had the same image if I had read the story in print, first.

On the subject of “exclusion,” I have a bone to pick.

There seems to be an approved list of oppressions and atrocities as subjects for fiction. The deportations by the Soviet government of a number of ethnic groups dwarf in size, in casualties, and in sheer nastiness, the Japanese internment of WWII. Seen any Anglophone stories set in the Holodomor? Me neither. No one seems to be protesting the exclusion of such oppressed minorities as Koryo-saram, Volga Germans, Crimean Tatars, Russian kulaks, Don cossacks, geneticists, students of Esperanto and abstract painters, all dealt with rather harshly back in the old country.

Amusing anecdote: I have my mother’s old 1950’s Soviet psychiatry textbook, somewhere. On page 100 there is a pearl the equal of which I have never seen - here in my translation:

Homosexuality is not necessarily a form of psychopathology. In reactionary societies where payment of bride price is customary, it may be the only possibility available to men of the poorer classes who cannot afford to marry.

I always wondered how drunk the editors had to be to come up with that.

I get the sense of Western civilization being singled out for criticism in both Western and non-Western literature, and I see this being accepted as the right and proper course, and I am not willing to leave this assumption unexamined in a comparative analysis. Suffice it to say that back in the old country at least, being “disregarded” was, for an individual or a minority population, the best of all possible states, and any kind of attention would have been immeasurably worse.

LUC: Now you’re bringing up a point that I don’t think I’ve really heard discussed before: prejudice and persecution of other cultures by other cultures. For instance, I suspect the reason we hear so little of Soviet oppression of the Koryo-saram (ethnic Koreans in the Soviet Union) in English-language literature is that English-speakers often have little familiarity with either Russians (and other Soviet cultures) or Koreans, to say nothing of Korean-Russians. It seems to be much simpler and more obvious for people who are trying to fight bigotry to focus on the bigotry of the people they know, yet the death by deportation and neglect of 40,000 Koryo-saram-not to mention some of the other atrocities you mention-dwarfs much of what happens in our own culture. What’s the case for learning about and writing fiction about persecution in other cultures?

ANATOLY:

It seems to be much simpler and more obvious for people who are trying to fight bigotry to focus on the bigotry of the people they know

There was an old Russian joke: a Russian and an American soldier are facing each other across Checkpoint Charlie. The American says, “It’s really better in the West. I can stand here all day yelling, “Down with Reagan!” and no one will bother me.” The Russian says, “So what? I can stand here and shout “Down with Reagan!” all day, too, and they might even give me a medal!”

I think the problem is better stated as, It seems more rewarding to focus on bigotry that affects them and the people they know. Which is a perfectly valid approach; my own activism, such as it is, is aimed at thwarting social - psychohistorical, if you will - forces that have a chance of leading us down the same terrible path as the one that had led to the 70-year Soviet nightmare, and to the crushing bigotry to which the resulting society subjected myself and my own family. And the first and most insidious of those forces is the demonization of success.

Before I get lumped in with Ayn Rand, I find demonization of lack of success equally repugnant. In fact, the only things worth demonizing are hypocrisy, in advocating changes sure to produce results opposite to those promised, and stupidity, in believing such promises.

What’s the case for learning about and writing fiction about persecution in other cultures?

Well, what’s the case against learning and writing about persecution in other cultures? Is it that it has no relevance to our world? Is it something that can’t happen here?

Or is it that, by pursuing one of these lines of thought, we…

…ritrovai per una selva oscura, che la diritta via era smarrita?

[find ourselves lost in a strange and darkened forest, where the direct path is lost — Dante’s Inferno]

as we realize that, in limiting ourselves to axes of oppression that intersect upon the standard model of privilege, we have been writing exclusively about spherical cows.

Let’s start with Internationale, which I remember by heart (in Russian, of course) having had to sing it countless times:

Весь мир насилья мы разрушим

До основанья, а затем

Мы наш, мы новый мир построим, —

Кто был ничем, тот станет всем.

We will destroy this world of violence

Down to the foundations, and then

We will build our new world.

He who was nothing will become everything!

Koryo-saram, Volga Germans, and others were not oppressed because they were poor, powerless minorities. They were oppressed because they were perceived to have power and privilege (in the form of land, a sufficiency of food, and a few non-spherical cows,) for not succumbing along with everyone else to revolutionary mismanagement. They were oppressed in order to make them into poor, powerless minorities that the Soviet state could then manipulate at will.

And to those who don’t think this has any relevance to the world we live in, I say: “Blessed are they who share the Universe with spherical cows.”

Anatoly Belilovsky

Anatoly Belilovsky came to the US from the USSR in 1976, learned English from watching

Star Trek reruns, worked his way through Princeton as a teaching assistant in Russian, and ended up a pediatrician in an area of New York where English is the 4th most commonly spoken language. It is perhaps unwise to expect from him anything resembling conventional fiction. His fiction appears in

Nature,

Ideomancer,

Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine the

Immersion Book of Steampunk, and elsewhere. He can be found online at

http://apogrypha.blogspot.com/.

Like this:

Like Loading...

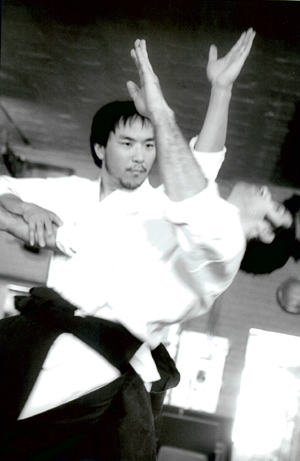

Luc: What’s the relationship between engaging with the world and engaging with an attacker? What approach or approaches does Aikido indicate for a practitioner who is being attacked?

Luc: What’s the relationship between engaging with the world and engaging with an attacker? What approach or approaches does Aikido indicate for a practitioner who is being attacked?

Anatoly Belilovsky came to the US from the USSR in 1976, learned English from watching Star Trek reruns, worked his way through Princeton as a teaching assistant in Russian, and ended up a pediatrician in an area of New York where English is the 4th most commonly spoken language. It is perhaps unwise to expect from him anything resembling conventional fiction. His fiction appears in Nature, Ideomancer, Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine the Immersion Book of Steampunk, and elsewhere. He can be found online at

Anatoly Belilovsky came to the US from the USSR in 1976, learned English from watching Star Trek reruns, worked his way through Princeton as a teaching assistant in Russian, and ended up a pediatrician in an area of New York where English is the 4th most commonly spoken language. It is perhaps unwise to expect from him anything resembling conventional fiction. His fiction appears in Nature, Ideomancer, Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine the Immersion Book of Steampunk, and elsewhere. He can be found online at

Aliette de Bodard lives in a flat with more computers than warm bodies, and writes speculative fiction in her spare time-her Aztec noir fantasy trilogy Obsidian and Blood was published by Angry Robot, and her short fiction has garnered her a British Science Fiction Award and nominations for the Hugo, Nebula and Campbell Award for Best New Writer. When not writing, she blogs and posts recipes over at

Aliette de Bodard lives in a flat with more computers than warm bodies, and writes speculative fiction in her spare time-her Aztec noir fantasy trilogy Obsidian and Blood was published by Angry Robot, and her short fiction has garnered her a British Science Fiction Award and nominations for the Hugo, Nebula and Campbell Award for Best New Writer. When not writing, she blogs and posts recipes over at  LUC: In our first round of questions, you mentioned Poppy Z. Brite’s book Drawing Blood, saying “Besides all the vampire sex and killing, what I took from that was that gay people are just people with relationships and problems and to do lists and lives to run and stories,” and you went on to describe how that has affected how you see and understand many kinds of people in the world. Are you consciously trying to create “aha” moments like this for your own readers? Are your goals for inclusivity in your writing explicit and specific?

LUC: In our first round of questions, you mentioned Poppy Z. Brite’s book Drawing Blood, saying “Besides all the vampire sex and killing, what I took from that was that gay people are just people with relationships and problems and to do lists and lives to run and stories,” and you went on to describe how that has affected how you see and understand many kinds of people in the world. Are you consciously trying to create “aha” moments like this for your own readers? Are your goals for inclusivity in your writing explicit and specific? LEAH: Actually, this might appear to come a bit out of left field? But: Anything by Sean Stewart. Specifically Galveston, or Nobody’s Son.

LEAH: Actually, this might appear to come a bit out of left field? But: Anything by Sean Stewart. Specifically Galveston, or Nobody’s Son.