A couple of posts ago I mentioned Malcolm Gladwell’s book The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, which digs into the ways phenomena go from puttering along to succeeding wildly, whether we’re talking about a book becoming a bestseller, a disease becoming an epidemic, or a big drop in violent crime. While Gladwell is specifically talking about social phenomena–how ideas and behaviors spread among people–it’s interesting to think about the possibility that tipping points may well apply to our own psychology, specifically in terms of a behavior transforming into a much more robust and consistent habit.

A quick disclaimer: the theory I’m putting out here is based on analogy, not research. It’s just an idea. If you believe Gladwell’s well-considered argument that making small changes like getting graffiti off subway cars and cracking down on people who demand money for squeegeeing car windows in traffic actually led to an enormous decrease in violent crime in New York City over a period of time, that doesn’t prove that making small changes in our own experience or thinking can tip a behavior into a habit.

Tipping points=easier habit formation?

And yet … much of the other material I’ve gathered for this site over the last few years does seem to support that idea. And if we really can think of habits as having tipping points, then that transforms our focus in terms of developing new habits. Instead of having to find huge resources to get ourselves to repeat a behavior over and over with great effort for months (see “How Long Does It Take to Form a Habit?“), we might mainly need to find the tweaks we would need to make repeating that behavior a lot easier.

Don’t get me wrong: creating a good habit (or breaking a bad one) is going to require time, effort, and attention no matter how you slice it. It’s just a matter of how easy and enjoyable that time, effort, and attention is. If habits have tipping points, then there may be a much easier way to create them than we’ve been used to thinking.

How my exercise habit tipped

I won’t go into this too deeply all in today’s post, but the basic idea is that relatively small changes we can make to circumstances might make a big difference in how our habits develop–if they’re the right small changes. I’ll give one example of my own, of when regular exercise became a kind of devotion for me instead of a chore. What made the difference wasn’t better scheduling, improving my attitude, or renewing my commitment: it was taking my workouts out of my own hands.

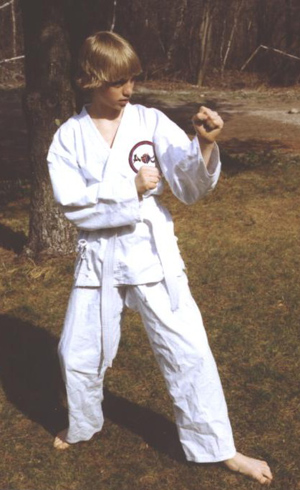

I started studying Taekwondo about four years ago (see my articles “Finding Exercise You Love: The Taekwondo Example” and “Black belt“). I had been used to getting myself out running regularly, which meant I always had to choose to run, find time to do it, choose how far I would go, and so on. Taekwondo was different: the times were set, and I had to show up for them or miss out. The length of the workout and the specific activities were also set. This one change–selecting a different exercise, which completely changed the context of my exercising–hugely simplified my problem of getting enough exercise, and my desire to get better at Taekwondo kept me coming back to class. Over time, all of this associated exercise powerfully for me with enjoyment, feeling good, and confidence. When I think of exercising now, these are the main things that come to mind, the mood boost and the pride I can take in what I’m doing. And even when I’m going running now or doing something other than Taekwondo, that kind of association draws me forward into exercise instead of repelling me, whereas thinking about the physical strain or being fat or the bad weather might be much more discouraging to someone who’s trying to exercise.

What was your tipping point?

I hope to write more on this topic in future. In the mean time, I’d be glad to hear from you: was there a tipping point for you in a key habit you’ve developed in your life? If so, what was it?

Photo by Captainspears23

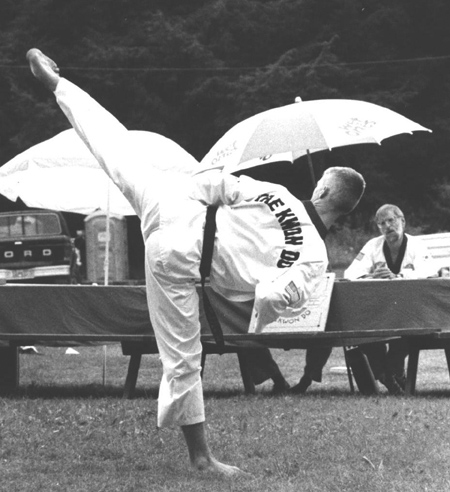

Gordon White at Nationals in 1997

Gordon White at Nationals in 1997

It started with bullies

It started with bullies

Becoming excellent at something really does take a long time. What’s more interesting is that, in a manner of speaking, that’s all it takes. In other words, that old saw “You can do anything you set your mind to” appears to have a lot of truth to it, truth backed by fistfuls of scientific studies.

Becoming excellent at something really does take a long time. What’s more interesting is that, in a manner of speaking, that’s all it takes. In other words, that old saw “You can do anything you set your mind to” appears to have a lot of truth to it, truth backed by fistfuls of scientific studies. All of this about talent that I’m casually summing up in a pretend conversation comes from the arguments found (among other places) in two recent, very well-written books. Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers does a lot to explain how the very best people in every field–music, chess, sports, business, and so on–all seem to have gotten their skills by working very hard for a long time. In fact, Gladwell will tell you how long that period of time is: 10,000 hours. It takes about 10,000 hours of practice in practically anything to become world-class at it.

All of this about talent that I’m casually summing up in a pretend conversation comes from the arguments found (among other places) in two recent, very well-written books. Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers does a lot to explain how the very best people in every field–music, chess, sports, business, and so on–all seem to have gotten their skills by working very hard for a long time. In fact, Gladwell will tell you how long that period of time is: 10,000 hours. It takes about 10,000 hours of practice in practically anything to become world-class at it.