This is the second in a series of articles that draw on the field of schema therapy, an approach to addressing negative thinking patterns that was devised by Dr. Jeffrey Young. There’s more information about schemas and schema therapy on a new page on The Willpower Engine here.

The Mistrust Schema

People with the Mistrust Schema expect bad treatment from others. They tend to think or say that they always get the worst of things, that other people want to do them harm, or that it’s not safe to trust others. Having a Mistrust Schema means feeling deep down, on a gut level, regardless of logic, that other people cannot be trusted, that the only safety is in keeping others at a distance.

Mistrust Schemas can be complicated or maintained in part by a person who avoids close connections with others out of fear of being hurt. This kind of avoidance encourages others to shun or disregard the person with the Mistrust Schema and makes it especially difficult to have any relationship that could prove the mistrust unfounded.

A person with a Mistrust Schema may also tend to jump to conclusions about others’ intentions and motivations, leading to unfounded accusations or preemptive counter-strikes–both of which, needless to say, tend to make others less well-disposed toward the person struggling with mistrust.

The Mistrust Schema generally is built early in life in response to abuse, whether emotional, physical, or sexual, by a person in authority or by anyone who is deeply trusted. A child who is mistreated will often naturally adopt a strategy of assuming the worst of other people in order not to be put in a vulnerable position again if it can be helped. While this behavior may help with the original untrustworthy person, it gets carried over to everyone else as life goes on, creating an emotional barrier that encourages isolation and fear.

Overcoming a Mistrust Schema

Relieving and eventually overcoming a Mistrust Schema requires an act of faith: consciously deciding to trust a person from time to time. A Mistrust Schema expresses itself in part as the broken idea known as fortune telling, in which a person makes assumptions about how the future will be (in this case, assuming that others will treat them badly), or in the related broken idea called mind reading, in which a person assumes things about how someone else is thinking (in this case, assuming that they are planning something unkind). For a person to come to grips with this schema means first noticing how it is affecting their life, behavior, and especially thinking: perceiving that this basic assumption that others will be hurtful is causing thoughts to run a certain way, then consciously rerouting those thoughts.

For example, a person with a mistrust schema may see a family member’s number coming up on caller ID before answering the phone and assume that the family member is calling to say unkind things. If the phone is answered with a hostile tone and the person with the mistrust schema is unkind or suspicious in the conversation, this encourages exactly the kind of behavior the person is predicting.

To cause the phone call to go another way, it’s necessary to stop and change the thought “That’s my sister. She’s calling to harangue me again.” to something like “That’s my sister. She may be calling to say something unkind, something nice, or just to pass on news. If I act kindly toward her over the phone, though, she may possibly talk kindly back.”

Small instances in which a person can demonstrate that mistrust is ill-founded can add up to greater confidence over time that can be used in situations that require more trust.

I’ll also mention that a good cognitive therapist can often be very helpful when a person is facing a major or ongoing problem like an especially bad mistrust schema. Even without the help of a therapist, though, it’s possible to take a stronger role in shaping our own mental landscapes when we’re aware of and deal directly with our own broken thoughts.

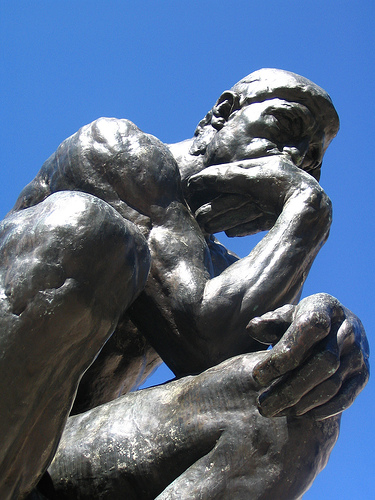

Photo by j / f / photos

Self-motivation and willpower can benefit from learning a lot of different skills:

Self-motivation and willpower can benefit from learning a lot of different skills: