In previous posts, I’ve recommended the online task manager Todoist for Getting Things Done-style organization. All the key features are available for free (though I subscribe to get the advanced features, paying $29/year). In March 2013, they introduced a tool called “karma,” a sort of ongoing game or rating based on how well you do at tracking and completing tasks. At the time, I must have thought it sounded to hokey or decided that the idea of having a productivity “score” was lame, because I didn’t start using it until five or six months ago. Since then, I’ve been a little amazed that it actually seems to work: I’m more productive, more focused, and more diligent specifically because of Todoist karma.

How can what basically amounts to a simple counting game help get more work done? By setting reachable goals and inspiring involvement. (For a more thorough consideration of the connection between games and motivation, read A Surprising Source of Insight into Self-Motivation: Video Games.)

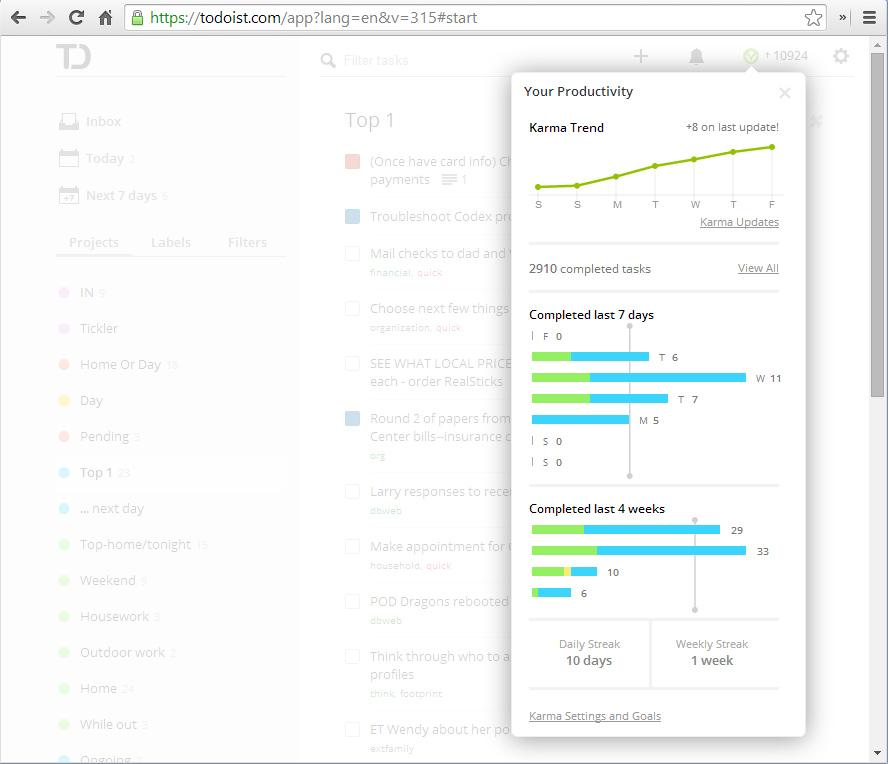

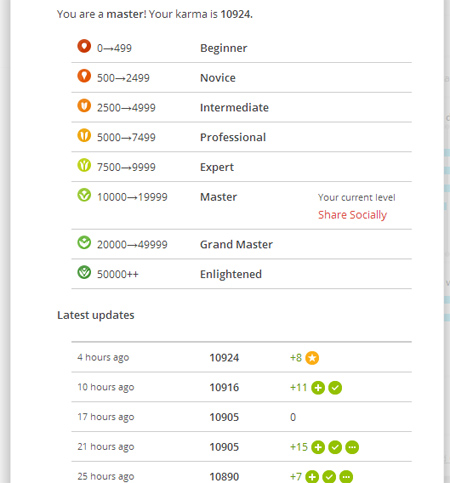

Let’s look at how that works. Here’s a screen shot of my karma as of today (click to zoom):

See the gray vertical lines, one for the last 7 days and one for the last 4 weeks? Those are my targets. I’m trying to complete at least that many tasks to keep on track, which is to say at least 5 per weekday and at least 25 per week. These are the default settings, which are actually great for me, but you can change them to whatever you want.

If I keep to these targets, my karma keeps going up, and my daily and weekly streaks (shown at the bottom) accumulate. (For more on motivation and winning streaks, see “Harnessing a Winning Streak.”)

As you can see from my streaks, I wasn’t able to keep on top of tasks in the same way as usual over the holidays, so I missed my targets several times up through the New Year, resetting the impressive streaks I had built up before Thanksgiving. Karma does have an important “vacation” feature (you just tell it that you’re on vacation, and it won’t expect you to get much done until you turn vacation back off). It also doesn’t expect you to get anything done on weekends (though you can change it so that you’re “on duty” any days of the week you like).

The rewards to attending to karma are minimal: your graph keeps going up, you build up your streaks, your score improves, and every once in a long while you “level up” to a new karma category. This may not sound like much inducement to get things done, but if you think about it, it’s very similar to a video game, and video games are notoriously addictive: you have a score, levels, goals, specific challenges … it’s not easy, but it’s not impossible … in a word, you’re engaged.

Another thing I like about karma that initially seemed like a drawback is that it mainly just tracks the number of tasks you get done rather than trying to deal with priority or importance or size. This makes it simple to use-pretty much automatic, in fact-but it also rewards breaking big goals down into small tasks, which is an excellent motivational and organizational technique. If you enter “redo flooring in dining room” in as a task, it’s a good bet you’ll never get it done. On the other hand, if you start with tasks like “Find out what kind of wood flooring options are out there” and “Measure dining room and write down dimensions,” then you’ve got a great basis for accomplishing something.

The way karma helps me the most is in setting a number of things to get done. My task list is probably thousands of items long, set up in many different categories with different priorities. To be productive, I have to get at least a few of those things done each day. Often what happens is that I’ll get to evening and have completed, say, three tasks (this is outside of my work task list, which I maintain separately). Being conscious of my Todoist karma, I’m aware that I can do two more to maintain my streaks and increase my score, or give up for the day, lose points and get my streaks reset. It’s nearly always possible to get two small tasks done, however, and so I generally do them, and this keeps my attention on what I have to do and also encourages me to do just a bit more each day. That’s exactly the level of quiet, private encouragement I need.

In short, if you’re in need of an elegant, easy-to-use, effective, and free task management system, you’ll have a hard time doing better than Todoist-and if you use Todoist, you should consider using the karma feature to engage more enthusiastically with all the tasks in your life.