Nancy Fulda is a writer, editor, entrepreneur, Web developer, and mom who created AnthologyBuilder, a service that lets people edit their own anthologies of short fiction by professional writers. Creating this service from scratch took a lot of doing, and is a useful illustration of tackling a big task with no immediate payoffs along the way. I interviewed Nancy about that process and about some of the unexpected insights into her own motivation that came out of it. The rest of this post, except for headings, is in her own words.

The idea: a site where people could create their own anthologies

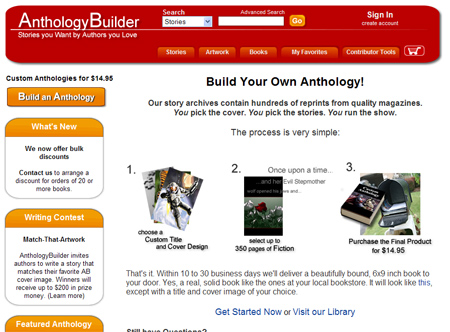

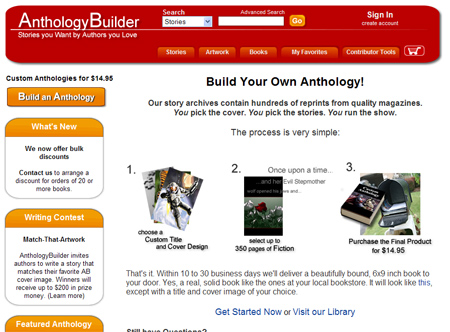

AnthologyBuilder is a custom anthology web site. Let’s say your nephew is fascinated by genetics and asks you for stories about geneticists. You’re not likely to find anything like that at the bookstore, but you can come to AnthologyBuilder.com and choose stories for inclusion in a mail-order book. You can pick your own title and cover art, too. The finished anthology costs $14.95 and looks just like any other book.

I started AnthologyBuilder because I was tired of buying magazines and books where only a few of the stories interested me. “What I want,” I said to my friends, “Is a do-it-yourself anthology web site that let’s me pick whatever stories I want.” The response was so overwhelmingly positive that I decided to build it.

I had a pretty good idea what the initial effort would be. I was a bit surprised, later, to discover how much work goes into maintaining and improving a project like this on a daily basis.

The first major obstacle

The hardest part was finding a programmer. I have some background in computing, so I had a pretty good grasp on what the site would need to do, and I was surprised and dismayed to discover that there weren’t any programmers willing to take on the job for rates we could afford.

“It’s not that hard,” I kept griping to my husband. “I don’t know why no one wants to do this. I could almost program it myself.”

And in the end, that’s what I did. It required teaching myself PHP, figuring out how to encode PDF documents, learning to purchase and administer web hosting, and brushing up on internet commerce, but after three months of work, the first prototype of the web site was ready to go.

How she stayed motivated

I think what helped most was keeping the Big Picture in mind. At the beginning, the web site wasn’t much to look at, but I tried to see it for what it could be instead of for what it was.

I made mistakes, of course; everyone does the first time they try something new. But I tried not to let those mistakes discourage me. I’d tell myself, “It’s ok, I can fix this. It will all work out in the end.” And so far, it has.

Starting a business from home, with kids

The home environment [was] an ideal work locale for me; I have the mornings to myself while the older kids are in day care. Afternoons get a bit crazy sometimes, but I often manage to sneak in an hour or two of work during the afternoon.

I tend to focus on one task at a time. There’s a weird sort of rhythm that I get into when programming. Some days, I can code up several web pages in far less time than it takes me to write a page of text.

My most productive work times — and this is going to sound odd at first — happened on the days when I spent the most time with the kids. Happy kids make for better work sessions, you see. Crabby children interrupt me more often, and I can’t concentrate well because I’m too busy feeling guilty. I learned pretty quickly to put the kids’ needs first even if there were five urgent emails in my in-box. I get more work done that way.

Dealing with distractions

One of the biggest hindrances at first was the number of internet communities I belonged to. I enjoy hanging out with my online friends, and I’d spend up to two hours catching up on blogs and discussion forums before actually settling into the work day.

After a while it became apparent that I was going to need to change something. It took some effort, but I finally convinced myself that I didn’t have to stay up-to-date on every thread of every discussion forum. In real life, I miss conversations all the time, so why should I feel the need to be a part of every single thing that happens online?

I also learned that I prefer to take care of the ‘little’ tasks of the day before settling into the ‘big’ one. By ‘little’ tasks I mean things like answering emails, paying the bills, and so forth; individual items that take less than five or ten minutes to accomplish.

I used to be so enamoured of the current project that I’d push all that little stuff aside and dive right into the ‘real work’. The problem with that was that all those unfinished tasks weighed on my mind. It was like a mountain of work hanging over me, this big dreadful pile of Things That Needed Done, and it sapped my energy like a vampire.

The thing is, that huge dreadful mountain tasks seldom took more than an hour to complete. I learned that if I cleared that stuff off my plate first, I’d face the rest of the day with only a single (albeit large) task looming over me.

How things changed once the business was launched

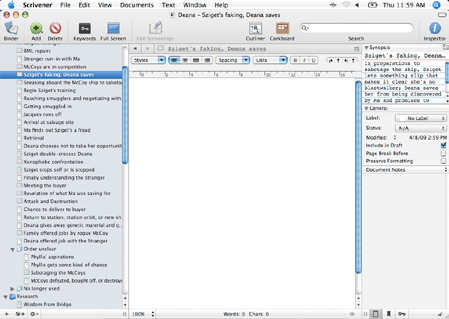

AnthologyBuilder seems to run in one of two modes: “Coasting” and “Renovation”.

In “Coasting” mode I spend 5-10 hours per week on housekeeping tasks: reading submissions, processing orders, responding to customer emails, and so forth. AB goes into Coast mode whenever life gets frantic. It’s a comfortable, familiar pattern that requires little emotional or intellectual investment.

“Renovation” mode comes along every two or three months and tends to last for about a month. This is where I implement new features, run promotions, rework the site design, and otherwise try to push the site to its next level of potential. Renovation mode requires 15-30 hours per week and sucks up a lot of brainspace.

When I’m in Renovation mode, I’m bursting with excitement and new ideas. I’ll find myself jotting notes down during breakfast or planning a new feature while playing with the kids. This saps energy and attention away from the family, which is why I try not to let Renovation mode continue for too many weeks in a row.

I envision my various projects (AB, family, work-for-hire, and so forth) as a connected system, kind of like push-buttons that pop up when one of the other buttons is pressed down. Whenever one project is the center of attention, all the others are Coasting. I try to swap it around and make sure every project gets its fair share of attention over time.

Sometimes I wondered whether AnthologyBuilder was unfairly sapping resources the family needed elsewhere. Every time I discussed it with my husband, though, we both felt strongly that we should stick with it. So we made adjustments and kept plugging along.

I would have abandoned the project without a second thought if I’d felt that AB was causing too much stress or that the family structure was cracking under the strain. I firmly believe that knowing when to let go of a good idea is just as important as knowing when to snatch one up and run with it.

Advice for entrepreneurs

I’m often asked what advice I’d give to young entrepreneurs. Two thoughts spring immediately to mind:

(1) Just because an idea doesn’t pan out doesn’t mean it was a mistake to try it. You gain skills along the way that will help make subsequent projects successful.

Perhaps more importantly, trying and failing brings a peace of mind that failing to try never can. Okay, so it didn’t work out, but at least you know that. You won’t spend the rest of your life wondering what might have happened if you’d tried.

(2) Don’t risk anything you’re not willing to lose. This includes, but is not limited to, money.

Family picture courtesy of Nancy Fulda.

Like this:

Like Loading...

This series of articles on distraction is adapted from my

This series of articles on distraction is adapted from my

As I write this it’s Saturday, the beginning of the first mostly-free weekend I’ve had in about a month. Because scheduled things take up almost all of my time during the week, I’ve amassed a list of about 30 tasks, large and small, that I’d like to get done this weekend. They probably won’t all get done, because there are only so many hours in the day, and that’s OK as long as I make good use of my time, enjoy the weekend, and get the most important ones taken care of. The question is, what’s the best way to do that?

As I write this it’s Saturday, the beginning of the first mostly-free weekend I’ve had in about a month. Because scheduled things take up almost all of my time during the week, I’ve amassed a list of about 30 tasks, large and small, that I’d like to get done this weekend. They probably won’t all get done, because there are only so many hours in the day, and that’s OK as long as I make good use of my time, enjoy the weekend, and get the most important ones taken care of. The question is, what’s the best way to do that?