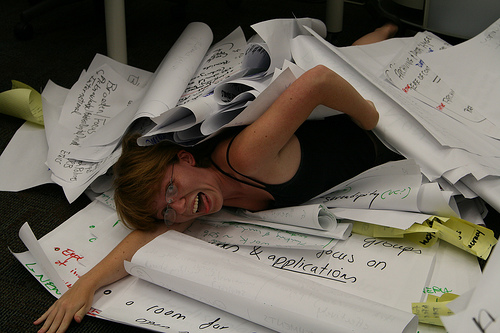

There are times when I feel a little overwhelmed with everything that is going on in my life. It’s my own fault: I have multiple, powerful interests, and follow them energetically, regularly creating new projects to add to an already busy schedule. In recent years I’ve learned to hold back, to mostly stick to just the most important and rewarding projects, but my task list is still long and varied.

This kind of life keeps me engaged and interested, and I get a lot done, but some days I feel as though there are so many things that it’s hard to know where to start. Fortunately, there are specific steps I can take to get back on track. There are also long-term practices I can follow to be more focused and serene in general, but I’ll tackle those in other posts.

1. Take a step back

Your first reaction to this might be “I can’t take a step back! I need to get these things done! And I’m right in the middle of ___!” That’s OK: that may be true. On the other hand, sometimes our general sense of anxiety about needing to get a lot of things done can make us feel as though the particular thing we’re focusing on–which sometimes isn’t nearly as crucial as it seems–absolutely requires our attention. Sometimes it does, but often this is a trap: if we’re always preoccupied with whatever we’re doing right then, we have no time to figure out whether we’re even doing the right thing.

So immediately if possible, or at worst some time soon when the opportunity presents itself, take a step back, breathe, and remind yourself that you’re only one person and, like it or not, will only get a certain number of things done that day. The priorities are to make the best use of your time and not to drive yourself crazy while doing it. Breathing and brief meditation exercises are sometimes helpful for taking a step back, as is simply getting into a quiet room and shutting the door for two minutes. Another good approach is to talk briefly to a friend who’s a good listener. Yet another, which is especially useful for people who like to be in action, is to briefly write out or type out the thoughts that are going through your head.

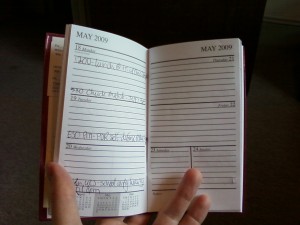

2. Write down what you need to get done

If you don’t write down the things you need to do, they may tend to chase each other around in your head, and worrying that you’ll forget one can be a source of additional anxiety. If you take a few minutes to list your tasks out, it’s true that it can be daunting because of having to face the whole list, but it’s also calming because it creates focus.

It’s helpful to write things down in a word processor instead of on paper because of the next step, but either way can work.

3. Get the unimportant things out of sight

There may be a lot of things on your list that would be nice to do, but that aren’t essential. It can help a great deal to move these off onto a secondary list. Depending on how much you have going on, you may never get to the secondary list, or by the time you get to it, it may be too late to do some of the items. This is OK! It’s far better to miss out on doing something unimportant than to fail to do something important because of being tied up with these secondary tasks.

If you keep the secondary tasks on the same list as the main tasks, though, they can add to feelings of distraction and anxiety. If you don’t need to do them now, get them out of your way, and remind yourself that they don’t need any of your attention right now.

There are some tips about prioritizing and feeling less distracted by secondary tasks in my post How to manage multiple priorities.

4. Pick the most important thing on the list and get started

This is just a little bit tricky, because we always need to balance importance with urgency. Importance is how much impact doing (or not doing) something will have, while urgency is how pressing it is to do it in the near future. More important things need to win out over things that are less important, but importance doesn’t always win out over urgency: that’s a judgement call.

One way to choose the task you should be doing at the moment is simply to ask “Which thing on this list will I be most happy to get done?”

And while it’s important to do a good job of picking the top task, it’s even more important to be willing to commit to doing the task you pick and not to let yourself be bamboozled by conflicting priorities into doing something unimportant.

That’s the short version, but while there’s certainly more to say on the subject, the sequence of taking a step back, reminding yourself of what’s important, focusing on that, then taking action on the most important thing for the moment will rarely let you down.

Photo by Cape Cod Cyclist.

I’d like to demonstrate some very useful ways this is completely wrong. I’ll do it using, of course, a mime.

I’d like to demonstrate some very useful ways this is completely wrong. I’ll do it using, of course, a mime.