Let’s say there’s something you really should do, but you dread doing it. Maybe it’s huge, difficult, inconvenient, dirty, unpleasant, draining, or even physically painful. Maybe you dread it because it’s a potential source of bad news (seeing the doctor, doing the bills, estimating revenues for the coming year). Maybe you started doing it, but you stopped, and now it’s been so long that you’re not even sure how you would begin. Or maybe it just has a bad association. Regardless, here’s something you’d really rather avoid but that you know you would be better off doing, preferably soon.

The problem is that dread is anything but motivating. If you could somehow dredge up some enthusiasm for doing the dreadful thing, that might get you somewhere, but dread tends to hold you back. Dreaded tasks often get ignored, avoided, delayed, bumped down the priority list by less important but more pleasant tasks, and so on. It’s certainly possible to take on a task while still dreading it, but transforming dread into something positive will nearly always make accomplishing the thing much more likely. So how can we do that?

Begin by Working on Motivation

The first thing to do is to separate the task of motivating yourself to do the task from the dreaded task itself. Motivating yourself is relatively easy and pleasant compared to cleaning out a filthy refrigerator or completing sixty pages of tax paperwork, and if you complete the job of motivating yourself, then actually doing the task becomes much easier.

In motivating ourselves to tackle a dreaded task, it’s important to begin to understand what about the task we dread, which means reflecting on our feelings and answering basic questions like “What is it I think will happen when I start doing this task?” and “What about this task is the biggest obstacle for me?”

With a bit of awareness about where the dread comes from, often idea repair and surrendering ourselves to the idea of taking on the task will clear away a lot of the dread. Sometimes talking with a sympathetic friend, family member, mentor, or therapist can help, as can writing about the issue in a journal.

Creating Enthusiasm Even for the Worst Tasks

And when the task is no longer as awful as it has sounded to us in the past, because we understand our feelings about it, have addressed broken thoughts, and have committed ourselves to taking care of business, we can turn to (as weird as this may sound) … enthusiasm. Even a task that seems terrible, if it’s related to something important to us, can have its attractions. One of the most appealing things about a really daunting task can be the vision of just getting it done: if the task is something that’s been put off for a long time, it’s probably a source of annoyance or anxiety, and doing it provides relief.

Dreaded tasks can sometimes be genuinely enjoyable (for instance, a trip to do something difficult could still be a fun trip); they may bring out a sense of pride at being the kind of person who can face these kinds of problems; and they can sometimes remove uncertainty about the future. More motivating even than these can be connecting with the really basic things you’re accomplishing with the task, for instance making your surroundings more welcoming, healing a damaged relationship, or working through a major financial issue. If it’s something you don’t feel like doing, what are your reasons for doing it in the first place? They’re probably significant ones.

Things to Watch Out for

If the task is large, it doesn’t have to be done all at once: doing a few simple things to get started can take a lot of the menace out of the thing you’re trying to accomplish and begin to establish momentum. If you don’t take care of it all at once, though, consider doing it in several sessions close together, for instance once per day until it’s finished, so as to keep that momentum going.

Regardless of how you approach it, there will probably come a point where you have to dive in. Whether you do this by distracting yourself or by finding courage, be prepared to have to pass this point when you start, and probably to pass it again from time to time as you continue. And when you’re done, you can take a good look back so that you’ll remember that you were courageous enough to get it done.

Photo by hapticflapjack

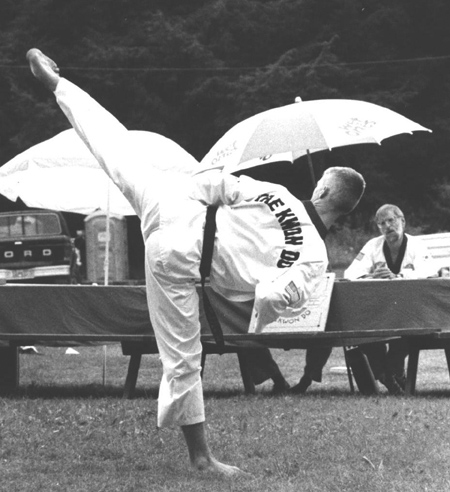

Gordon White at Nationals in 1997

Gordon White at Nationals in 1997

It started with bullies

It started with bullies

But it’s easier for me than for my son, because I’ve been folding clothes for decades, while my son has only been doing it for a few years. Several times every folding session, I’ll notice he’s stopped folding, his attention fully on the movie. Usually this happens with a trickier item of clothing or with a particularly gripping part of the movie. Not being as used to folding as me, he can’t do it entirely on automatic, so his brain needs some of his attention for the folding, and his attention is already taken up by the movie. Since he can’t pay attention to two things at once, the clothes folding just stops, and since he was doing it automatically, he may not even notice: he may just sit there holding the shirt, transfixed.

But it’s easier for me than for my son, because I’ve been folding clothes for decades, while my son has only been doing it for a few years. Several times every folding session, I’ll notice he’s stopped folding, his attention fully on the movie. Usually this happens with a trickier item of clothing or with a particularly gripping part of the movie. Not being as used to folding as me, he can’t do it entirely on automatic, so his brain needs some of his attention for the folding, and his attention is already taken up by the movie. Since he can’t pay attention to two things at once, the clothes folding just stops, and since he was doing it automatically, he may not even notice: he may just sit there holding the shirt, transfixed.