Do you have to have an organizational system in order to motivate yourself? No. Does it help? Hell, yes.

In order to motivate ourselves toward specific goals, we can identify a set of factors that we either need or at least benefit a lot by. Among these are a few important ones that organization helps with in spades, specifically:

1. Setting and prioritizing goals

2. Understanding what needs to be done, and

3. Getting regular, meaningful feedback (in the form of checking things off)

If I’m pursuing a big goal (whether it’s completing a book proposal, renovating a house, or learning to speak Bantu), in many cases the most productive thing for me to do is to break that big task into steps, and the steps into smaller tasks, until I get down to the level of tasks that can be done in one pass. This is less important with goals that are more repetitive (for instance, speaking Bantu: if I set up regular lessons and study times, I should be fine) than with goals that are made up of a wide variety of little things (like cutting window glass, taking down cabinets, and painting for that house renovation) that may be hard to keep track of. If I’m doing one big task of the second kind, organization becomes important. If I’m doing several big tasks like that, or lots and lots of little tasks, organization becomes the difference between being productive and being driven profoundly, dramatically nutty. Anyone who forgets to do important things, does low-priority things when they would rather have been doing high-priority things, feels scattered or overwhelmed, or doesn’t know where to start on the mound of things ahead can probably benefit from better organization.

It’s important to realize that organization itself requires self-motivation to be trained into a habit. Since we’re motivated to do things that we feel happy about and tend to avoid things that we feel anxious about, it’s very helpful to consciously associate the organization you do with the relief it brings, whether that’s at the “Well, at least now I know everything I have in front of me” level or at the “Hooray, I’m finished!” level of achievement. If you find yourself avoiding your organizational system, try taking a step back and thinking of the benefits of your system, of anything it has helped you do in the past, or of people whose organizational skills you admire. Thinking positively about organization makes doing organization much more appealing.

Which organizational system you choose will also make a lot of difference. A paper system can work if you don’t have a lot of tasks or if you don’t mind writing and rewriting things a lot, but electronic systems make things much easier by helping group and prioritize tasks, dropping completed tasks from your list, and so on. Many electronic organization systems also allow you to keep different categories of tasks, which is important: ideally, you want to categorize your tasks so that at any given time, you’re only looking at the things you could conceivably get done right then. It can be anxiety-producing to look at a monumental list of tasks, 90% of which you can’t do now because you’re in the wrong place, have only a limited amount of time, etc.

Because of this, I tend to break out my own task lists in four ways: first, by where I do them, in that I use a completely different organizational tool for work compared to home, since it’s rare that I’ll have the choice of doing either of those things at the same time. Second, by theme: I have one task list of things to do with my son, another of strictly writing-related tasks, another of financial tasks, etc. Third, by task length: I tend to keep a separate list of very quick tasks that I can get done when I just have a few spare minutes. And fourth, by importance: I find it helpful to keep a list of top tasks so that they don’t get ignored in favor of easier but much less important ones.

Of course, this results in a lot of lists, but then, I don’t categorize every single task in all four ways. For instance, my most important tasks just go in the “top” list regardless of other concerns, and my “quick win” short task list contains both important and unimportant tasks (although it’s prioritized within that).

The goal of all this separation of tasks (which is probably overkill in that form for most people, as I tend to have a lot of complex things going on at any given time) is to have a set of task lists that I can choose from whenever I’m ready to do something productive. If I’ve blocked out time for writing, I look at the writing list. If I have a few spare minutes, I look at the “quick win” list. If I’m going out to run errands, I look at my errands list. And so on.

With any luck, your list of things to do is much shorter than mine, and you would need at most only a few categories.

Any task management system needs to be one you can access conveniently and often. A computer-based one is no good if you’re rarely at the computer, for instance. And any system that makes it hard to figure out what you should be doing (like a paper system where you have to sift through a pile of notes) or that takes too long for you to access (like a computerized system that takes a long time to start up) or that makes it hard to read or enter tasks (like a task list on your cell phone when you don’t have an alphanumeric keypad on your phone) is probably the wrong one.

In terms of my favorite tools, here’s what I’m using at the moment.

First and foremost, I use Todoist, a completely free, online system that offers one of the easiest, most natural, and most convenient user interfaces I’ve ever seen anywhere. While it does offer ways to prioritize and schedule due dates, generally speaking the main thing I care about is typing the task in as part of the right category. To do this takes me one double-click (to open the shortcut to the Todoist site on my desktop), one single click (to select the project I want), and one keystroke (“a” to staring adding a new task). Once I have the task in, it’s easy to edit, schedule, prioritize, move between projects, or move to a different place on the list with drag-and-drop.

Of course, fully using Todoist means I need to be at the computer, but when I’m not I print out my tasks if I need to consult the list, and write down a list of any that I need to add–which it’s then essential that I add as soon as possible, so that everything stays up to date. On top of that, though, since I have Web access on my phone, I can get to the mobile version of Todoist through that, which is very limited in terms of functionality, but where I can easily view my tasks and add new ones.

In terms of my calendar, to my own surprise this year I’ve adopted a simple, paper-based planner booklet. I find it much easier to see what I’ll be doing at a particular time by flipping to a page rather than by having to look something up on the computer, and writing things in a schedule doesn’t have the drawbacks of keeping tasks on paper, because old events are just ignored as you flip to the new page. One major limitation of this system, it should be noted, is that you don’t get reminders, but I address that by checking my planner often to keep myself aware of my schedule. If I really, really needed a reminder, I could enter alarms into my cell phone.

A good alternative for both of these systems is a PDA (personal digital assistant), like a Palm Pilot or a Blackberry. Older Palm Pilots that are still completely functional can often be gotten on eBay for $30 or less. The main reason I’ve stopped using my PDA in favor of these other systems is the niggling details of convenience. Since it’s much easier for me to enter tasks into Todoist or events into my planner than to enter either into my Palm Pilot, I find I’m more reliable about keeping information up to date when I use these methods. The benefits of “convenient” for things that we sometimes don’t feel like doing are hard to overstate.

Finally, a note about overcommitment, an issue I struggle with: if you have chosen to do more things in your life than you’re willing or able to find the time for, not only will you never feel caught up, but you’ll fail to do things you had wanted or promised to do. That is, if you choose to do more than you can realistically get done, you really won’t get it all done, and what you don’t get done will be chosen by circumstance instead of by you. The only completely sane solution to this is to take a hard look at your commitments and decide what you can do less of. The temptation is to promise yourself you’ll do less of the recreational stuff, and often this can be a good way to go for at least part of the problem–but it can also be hard, because every time we sit down to watch a television show or kill some time randomly surfing the Web, we’re acting not only on habit but in response to some internal desire, need, or gap. Tackling these kinds of issues takes mindfulness, self-examination, and willpower, and fortunately this blog is designed to help in all of those departments.

Of course, there are uncountable organizational systems, tools, programs, practices, and paraphernalia, and what works best depends a lot on the individual person. Do you have something that works very well for you? I’d love to hear more about it in comments.

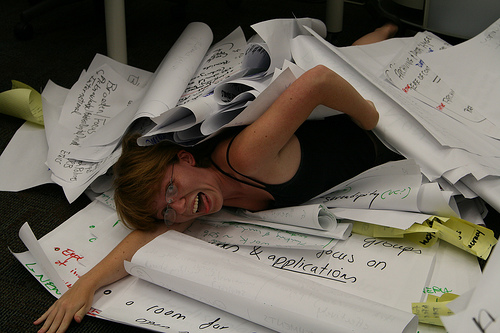

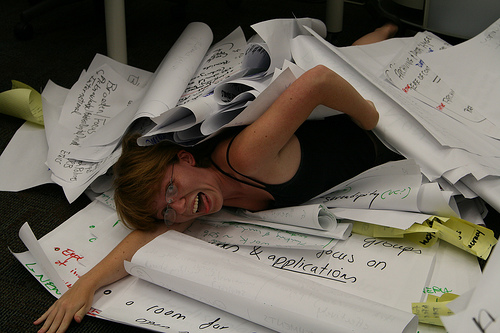

“Drowning” photograph by Quinn.Anya.

Like this:

Like Loading...

I came across an interesting post today on a blog by Ross Hudgens, which talks about managing his immediate environment to aid his willpower in losing weight: for instance, he takes only a set amount of cash with him when he goes out to bars, leaving his ATM and credit cards at home, making it very difficult to go out and binge eat. He also keeps his cupboards bare of junk food so that unhealthy snacking requires a separate trip to the store. (There are other interesting posts on Hudgens’ blog, although I can’t recommend all of them. While Hudgens turns up a number of good ideas, I think some are more useful than others.)

I came across an interesting post today on a blog by Ross Hudgens, which talks about managing his immediate environment to aid his willpower in losing weight: for instance, he takes only a set amount of cash with him when he goes out to bars, leaving his ATM and credit cards at home, making it very difficult to go out and binge eat. He also keeps his cupboards bare of junk food so that unhealthy snacking requires a separate trip to the store. (There are other interesting posts on Hudgens’ blog, although I can’t recommend all of them. While Hudgens turns up a number of good ideas, I think some are more useful than others.)

This means you have an opportunity for some motivational groundwork–visualization, for instance–that can make good decisions during the rest of your day easier and more enjoyable, because most of the time when we actually need to motivate ourselves, serenity and lack of distractions are hard to come by.

This means you have an opportunity for some motivational groundwork–visualization, for instance–that can make good decisions during the rest of your day easier and more enjoyable, because most of the time when we actually need to motivate ourselves, serenity and lack of distractions are hard to come by.