You may not be someone who’s trying to lose weight, eat a better diet, get more exercise, or in some other way make changes to become more fit or healthy–but if you aren’t, you’re probably in the minority (and I tip my hat to you).

For the rest of us, I’ll skip the prolonged introduction and go straight to the useful information. And while you may have already heard this a thousand times, just in case, I’ll mention that the real goal here has to be becoming comfortable with leading a healthy lifestyle. Anything short of that will quickly turn on you and bite you in the butt.

1. Know what you should be eating and keep careful track

Most of us have no idea how much we’re actually eating in a day, and many of us have no idea how much we should be eating if we want to lose weight. Do a little research to figure out what your daily food intake would need to be for you to lose weight, then faithfully keep track in terms of calories or some other good measure, like exchanges. To find out calorie counts for a particular food, a Google search for the name of the food plus the word “calories” usually does the trick. It can be helpful to keep a list of foods you eat often and what their counts are for reference.

Not keeping track of this information means that we remain ignorant of the impact of the things we’re eating, so that the reasons behind not being able to lose weight remain a mystery. If we know the impact of each thing we eat, we then have the information we need to make good choices.

2. Pay attention to how you feel and what you’re thinking

Many of us eat badly in response to stress or other negative emotions, or for very unconstructive reasons, like wanting to be polite or because an unusual food happens to become available. The more mindful we become of what is going through our heads when we’re faced with decisions, the better equipped we are to deal with our own thoughts and emotions instead of to automatically revert to bad eating habits. To really notice our own thoughts, we have to take a step back right at the moment of choice–for instance, just as we’re deciding what to have for lunch or whether or not to go exercises.

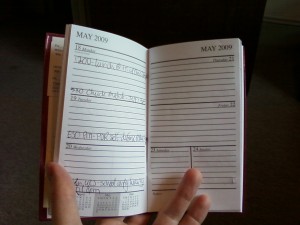

A technique that can really help here, once a thought is recognized, is idea repair. Another is something I call “decision logging,” which means jotting down thoughts, feelings, and any other conditions throughout the day that might influence decisions. Doing this for a couple of weeks can provide a truckload of insight into where our feelings and inclinations are coming from, and it can show where the opportunities are to cut off negative emotions before they really kick in. This process can be useful for much more than weight loss, of course.

3. Visualize your goals

Spend some time on a daily basis–even just a few minutes–imagining yourself having achieved your goal, and allow yourself to enjoy the feelings of having done it. It’s much easier to be motivated by positive emotions (even if they come from imagining things) than it is to be motivated by vague inclinations. Negative emotions–guilt, shame, frustration–are lousy motivators, and are unlikely to be able to keep you consistently working on a tricky task for long. Use encouraging visions of the future as a continuing source of pleasure to associate with your process. The more you enjoy what you’re doing, the better you’ll do at it. And speaking of which …

4. Enjoy the steps

It’s easy to tell ourselves that exercise is painful and inconvenient, or that eating something healthy is boring. And certainly any process of changing major habits has its hard parts. If we focus on those, though, then again we’re associating negative emotions with our process instead of positive ones, and that won’t get us very far. Instead, it helps to focus, again and again, on the positive or pleasurable parts of the things we need to do. If I’m out running, I can put my attention more on the beauty of the park I’m running through or on the fact that I’m getting a quarter of a mile further than I was getting a week ago rather than on the physical effort or concerns about how I look, for instance.

There is something to enjoy in virtually any good step we take. Even hunger can be enjoyed when we have to experience a small amount of it while changing our eating habits, for instance because of the feeling of success and virtue, or because it’s an indication that we’re doing something that’s working.

5. Set up a feedback loop

Unless we reflect on our successes and mistakes, we tend to repeat the mistakes and only stumble on the successes now and again. At least once a week, and preferably more often, it can be a huge help to reflect on what you did, how it went, and what you want to do in the future. This will help keep you on track.

There are a variety of ways to set up feedback loops. Some commercial weight loss programs offer weekly group meetings and weigh-ins, which can work very well. Buddies can also work well, as can blogs, online forums, and journaling. More public ways of getting feedbacks (like groups and blogs) also can up the stakes for doing well, which can be very motivating to some people (but too much pressure for others). Choose the method that works best for you and make it a priority to do it regularly. If you miss a round of feedback, be sure to include that in the things you consider the next time. In other words, even your feedback loop can benefit from feedback.

6. Cut short arguments with yourself

Many of us are used to looking at choices we really want to steer clear of–often about a food that we don’t need and that would throw off our calorie count for the day–and then debating with ourselves, trying to convince ourselves to follow the virtuous path. But between a piece of chocolate cake and some vague idea of virtue, chocolate cake very often wins, so an alternative strategy is to turn around and walk away, immediately–even if the debate is still going on in your head. You don’t have to convince yourself to avoid something that would be bad for you or to do something that would be good for you if you simply go ahead and take the best available action. Concentrate on the simple physical acts: turning and putting one foot in front of the other, or putting on your workout clothes. These kinds of behaviors can shortcut the endangered decision-making process and help support automatic positive behaviors.

As always, there’s a lot more we could say on this subject, but this is a good start for now. And just so you know: I’m neither a professional nutritionist nor a psychologist. I’m also not qualified in any way to give you personal medical advice.

However, I’ve been studying the factors that go into self-motivation intensively for some time now and have myself lost upwards of 40 pounds while becoming much healthier. Don’t make me post before and after pictures, because I will if I have to. Regardless, I hope you’ll find these ideas useful and comment with questions or about your experiences.

Bike picture by Erica_Marshall

Shoe picture by Fey the Ferocious Feyrannosaur