An experiment in excuses

For most of my life I’ve been running an experiment between two categories of things in my life: the “excuses are OK” group and “no excuses” group. It’s only recently that I noticed I was running this experiment, though, and so the years and years of results are only now starting to come in handy.

Let me give some examples of choices that have been in each group. By the way, though I talk a lot about eating well in this post, the points about excuses and exceptions apply just as well to forming any other kind of habit.

“Excuses are OK” group

- Eating foods that I’d be better off not eating

- Going to bed at a reasonable hour

- Keeping track of incoming mail

“No Excuses” group

- Parenting

- Vegetarianism (for the 22 years I decided to do that)

- Going to work

So I might do well for a stretch at making good eating choices, then hit a day when I was traveling and didn’t have many options, so I’d say to myself “Oh well, it’s really hard to eat well on a day like today–I’ll just eat whatever.”

But on that same trip I would not say “Oh well, it’s really hard to eat vegetarian on a day like today–I’ll just get a hamburger.”

My results

Knowing what I know these days about self-motivation, it shouldn’t surprise me that the “no excuses” group of activities were much more successful than the “excuses OK” group. For instance, when I started making a rule of eating only at specific times of day, it became much easier to make better eating choices. I went 22 years without knowingly eating any red meat, seafood, or poultry–even that time back in my 20’s when I was out of money and extremely hungry while traveling and someone offered me a hamburger. By contrast, it’s rare that I’ve gone 22 days without overeating (though all the days I have eaten well count for something, as I eventually lost 60 pounds and have been in great shape for quite a while now).

To look at it another way, and in terms of a real experiment, one study on habit formation found that those participants who kept up the behavior they wanted to make into a habit with no more than one exception over the course of months were much more successful at forming durable habits than those who made two or more exceptions.

The secret of excuses and exceptions

The thing about excuses and exceptions is that if we’re trying to build habits, there’s no good reason for excuses short of total catastrophe. Any time we don’t stick with the behavior we’re trying to build up–that is, any time we make exceptions–we lose some of the habitual behavior we’re trying to build. There may be days when eating well is inconvenient, boring, or annoying, but if I use inconvenience, boredom, and annoyance as excuses, then they’ll wreck my attempts to build a habit over time.

That’s not to say that making one excuse is the end of the world, but it is true that taking excuses as a serious problem and not an acceptable norm will help us develop the habits we want to create.

Easier said than done–but possible!

“That’s really nice,” you might say, “but it doesn’t help me for you to just tell me to behave the way I’d like to all the time. Not behaving the way I want to is the problem in the first place!” And that would be a reasonable thing to mention. Fortunately, there is a practical takeaway here: excuses are red flags and should be treated as such. There’s no such thing as a good excuse when trying to build a habit, there are only catastrophic interruptions. If a friend of yours is in the hospital and you end up throwing your good eating habits out the window from stress and limited choices, that’s fine; it’s not the end of the world–but it is a catastrophic interruption, and it means you’re damaging a good habit you’re working on for something more important. But good friends are more important than good food, and that’s a reasonable choice if you really need to focus on your friend.

On the other hand, what if you just interrupt a good habit because you’re in a bad mood or happen to be in a restaurant that serves something you like? Many of us immediately reach for the excuse box.

But if we recognize excuses and exceptions as danger signs, we can stop ourselves and say “My goal here is to build a habit, not to come up with excuses to screw that up.” Using this kind of awareness, making rules, taking responsibility, surrendering excuses, and making use of any useful tactics we can learn (like this list of 24 Ways to Stop Feeling Hungry), we can move ourselves out of the “Excuses OK” group and into the group that’s really kicking experimental butt.

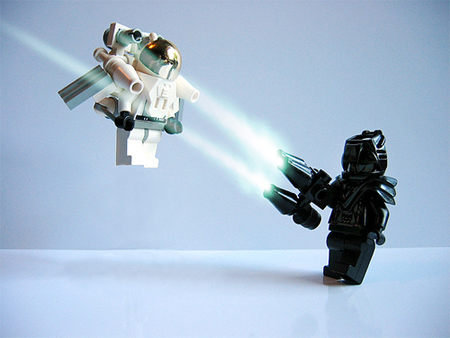

Photo by ariel.chico