Earlier this year, my partner Janine and I had the chance to study with parenting educator Vicki Hoefle, whose Parenting On Track™ program, with its roots in Adlerian psychology, strikes off in a completely different–and more effective–direction than any approach to parenting I had ever come across. Vicki has kindly made some of her parenting articles available to me to reprint here. If you’re interested in the topic or have questions, please comment to help guide me in choices for future posts.

I don’t usually post guest articles that promote a particular product, but I do strongly recommend any Parenting on Track book, course, or media you may be inclined to buy, and I hope that if you’re not inclined to buy anything you won’t be put off by this departure from my usual way of doing things.

This article originally appeared at http://www.parentingontrack.com/2008/06/if-they-can-walk/ .

If you’re beginning to wonder if you’re the maid or the parent, then…

A) You’re not alone

B) Now’s the time to do something about changing roles, and

C) Believe it or not, both you AND the kids will be glad you did now, and for years to come.

I realized at an early stage in my pregnancy with my first child that I could either be the maid or be emotionally available to my children, but I could not do both. Since there’s a far greater payoff to being emotionally available, I decided to train my children early on to help with the household chores.

Now, if you’re at all put off by the word train, here are a few other verbs straight out of my thesaurus: teach, coach, educate, instruct, guide, prepare, tutor… and you’ve got to love this one… school.

I use the word train because that’s what it is. And let’s face it, training is useful – it makes us all better at what we do. And knowing how to learn from our training is a skill in and of itself. A skill, I might add, that will serve your children well as they go off to school, into the workplace… but that’s another topic for another day. Back to making everyone’s life easier and more pleasant by taking off that maid’s outfit and giving your children a chance to be part of the family fun.

Is there an optimal time for training?

The quick answer is YES! Over the years I developed a very simple answer for parents when they would ask me how young they could start training their children to help around the house. My answer is, “If they can walk, they can work.” That’s right moms and dads, it’s never too early.

There are two good reasons to start training your children in what is essentially the fine art of cooperation and contribution, as soon as possible.

1. The first reason is that, if children have been invited to participate in family chores from a young age, contributions will be a normal and routine part of their daily lives by the time they hit the pre-adolescent, “I am not interested” age. So, it’s actually less painful for both you and your kids if you start ‘em young.

Consider this. When our children are very small, they come to us asking to help and we are quick to reply with, “No, too hot; too heavy; too dangerous; too sharp; too fast; you are too little; too slow; too short.” And then we send them out of the kitchen and into the other room to play with the plastic kitchens and plastic food and say, “Now go play and have fun.”

We continue to do this, over and over, for years, until one day, about the time that same child turns 10, WE decide it’s time for them to be responsible for their stuff and we start in with, “Hey, pick up your back pack; unpack your backpack; put your dishes away; clear the table; pick up your room; do your laundry…” Sorry ladies and gents, but by then, it’s too late! We have missed the most opportune time for training.

You see, when children are very, very interested in just about everything around them – including mimicking mom and dad, you, as a responsible, pro-active parent, can use that natural curiosity to everybody’s advantage and get everyone involved in doing their part around the house.

2. The second reason to start training your children early to contribute to the household chores is a very practical one – kids need years of practice to become good at doing “stuff” around the house.

Just take a second and look around your home. I’m sure you’d agree that tasks which truly contribute to running even the simplest of households require some pretty complex skills, and developing any skill takes practice, more practice, and even more practice. The sooner you start practicing a skill, the sooner that skill develops.

So, just how should I go about training my toddler to contribute to the household chores?

Here are a few things to keep in mind:

- An immaculate house is NOT the primary goal. If you want it clean to your standards, wait until the kids are in bed and clean it yourself – but for goodness sakes, don’t get caught!

- Set reasonable expectations based on the child’s age.

- Notice what your child is doing, and talk about it.

- Train in small time increments.

- Start with something relatively easy, like putting back toys, then move on to more advanced tasks like picking up trash and helping with the dishes.

The following checklists should help you get started with your first attempt:

Planning Basics

- What two jobs can my toddler attempt successfully?

- When am I going to train him or her? (Pick a time in the day that works for you and your child.)

- What are my expectations?

When Your Child Says, “No”

- Smile and walk away.

- Go do something more interesting like read your book, listen to music, paint…

It’s also good to keep in mind that training in the art of cooperation and contribution doesn’t have to be explicitly planned during the early stages of training. As long as you’re ready when the opportunity presents itself, you can instill this spirit at a moment’s notice.

When Your Little One Tugs On Your Pant Leg to Play

- Say “Yes, I would LOVE to play with you, as soon as we use bubbles to wash the dishes!”

- Ask another question like “Would you like to learn how to squeeze the dish soap or turn on the dishwasher?”

Above all, DON’T GIVE UP — the ability to cooperate and contribute is a life skill that takes practice. And, whether you know it or not, your little ones will notice that you never give up on them, and that means the world.

If you have stories about how life has changed, now that you have handed in your feather duster and started training your kids, please share your comments below!

For more information on HOW to stay patient, set reasonable expectations, teach in small increments, and encourage your child (& yourself) along the way, purchase our Home Program and join the forum — Today!

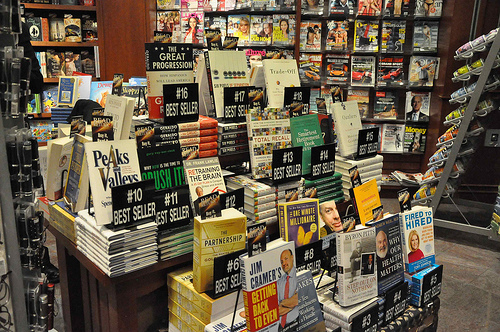

Photo by horrigans

Like this:

Like Loading...

Recently Janine and I attended a series of six weekly classes (with substantial homework assignments) taught by parenting advisor

Recently Janine and I attended a series of six weekly classes (with substantial homework assignments) taught by parenting advisor