Back in February I posted the article “How I’m Keeping My E-mail Inbox Empty” after applying many of the things I’ve learned in researching organization and self-motivation, particularly David Allen’s excellent book Getting Things Done. Since then I’ve had no trouble keeping my inbox empty, especially with tricks I learned since (see My Empty E-mail Inbox, 10 Weeks Later), except that, since I often read and answer e-mail on the go, I haven’t been able to use desktop e-mail applications I used to use like Outlook and Apple Mail. The problem with using these is that if I look at the same e-mail account with more than one system, I have repeat all my organization and inbox cleaning in every one of those–which means that it just won’t get done. Who wants to get home from a trip, for instance, and have to reorganize two hundred e-mails that were already organized on a laptop while away?

Failed (and not-so-failed) free e-mail options

I’d mentioned I was using a Web-based e-mail application provided by my ISP, but I’ve been disappointed to find that this application, although it has most of the features I want, is buggy and sometimes intolerably slow. So I’ve been searching for a replacement program I could use, something freely available on the Web that I could also recommend to my readers here.

[Added after the original post: If you’re interested in using GMail with this approach, please see the comments, where D. Moonfire offers a potential solution to the problem I’m about to describe.]

You’d think I’d go with GMail, since it’s robust and efficient and feature-packed, but GMail is fundamentally unsuited to the task of keeping an empty inbox, because it doesn’t use folders: instead, it uses tags and categories. Rather than moving something off into a folder, you tag it with the folder name. This seems handy, and can be, and it also allows a single message to be categorized in more than one way, but since nothing can ever be moved out of the inbox, that means that there is no way to reap the organizational and psychological benefits of a clean inbox with GMail at all. Instead of facilitating a clean inbox, it assumes you’ll never be able to keep your inbox organized and doesn’t even provide the means to manage it. If it were a human being, we’d call it an Enabler, which in this case is not a good thing.

There may be ways around this in GMail; I’ll present them if I come across them.

One that works: Hotmail

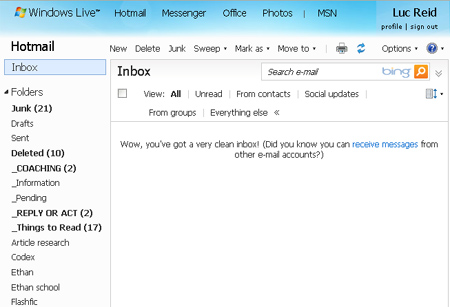

The system I found that does work and that is free to all comers is Hotmail, a.k.a. Microsoft Live Mail. If you despise all things Microsoft, of course, this won’t appeal to you, but otherwise it does the job fairly well. You can set up Hotmail to receive e-mail from other accounts and can organize all your incoming e-mail into folders. They even recently added a feature that gives you a little congratulatory message if you empty out your inbox (though I have a feeling this isn’t a message very many people see.) Hotmail is easy to use, has drag-and-drop functionality, and is very responsive.

There are a couple of drawbacks. One is that Hotmail doesn’t allow subfolders, so I can’t make categories out of my folders and collapse them when I don’t need them. It also doesn’t allow very long folder names. This is inconvenient, but I’ve worked around it by naming folders things like Read_offers instead of having an “offers” folder within my “read” (as in “already read”) folder. I also had to place underscore symbols at the beginning of the names of my utility folders so that they would be listed together at the talk, as Hotmail always shows folders alphabetically.

The other drawback is that it often seems to take about 10 minutes (very roughly) for an e-mail to arrive from an external e-mail account. Normally this doesn’t matter much, but it’s a big obstacle if you’re having a semi-real-time e-mail conversation with someone, if someone sends you something while talking with you on the phone, or if the correspondence is time-sensitive. This delay doesn’t occur with the free account you get from Hotmail itself, though.

So while I can’t recommend Hotmail wholeheartedly, I can say that for the month-and-a-half or so I’ve used it, administrating my e-mail has been easier than it ever has been before because Hotmail supports the “empty inbox” approach very well.

Any readers who have recommendations of other free or very affordable Web-based e-mail systems they would recommend for this purpose are very much encouraged to mention them in comments.