What’s your biggest goal right now, the one you most want to tackle? If you don’t know that off the top of your head, that may be a big obstacle to getting much done. If you do know, great–and on to the next question, which is this: what is the very next thing you’re going to be doing to further that goal?

Do you know that one off the top of your head? If so, go to the head of the class! If not, you can still go to the head of the class, but first you have to get in the habit of queuing things up for yourself. It sounds simple and inconsequential, but it’s actually simple and crucial.

The logic is pretty straightforward: if I know what my next step is, then I’ll recognize as soon as there’s a good opportunity for me to take it and am prepared to take that opportunity. Once I’ve tackled that step, I take a moment to think about the next step so that I know what that is. Working this way, I’m never that far from thinking about or being able to act on my goals, and sometimes my subconscious may even be able to make extra progress on my project without me expending any real effort.

Looking at it from another perspective, knowing your next step is an effective way to minimize anxiety about a big project. If there twenty things you could do next and you haven’t picked one as being the first, then you’re in a position where you have to worry about all twenty. If you’ve carefully chosen one of those things to do next, you only have to worry about that one until you complete it; then you choose the next one and still only have to worry about one, even though you’re moving right on down the list.

By the way, “the next step” means something that you actively have to focus on to do. If the next thing you need to do to achieve your goal is something that you don’t even have to think about, something that’s already set up for you or already an ingrained habit, ignore it for the purpose of knowing what’s next. But those are specifically the kind of areas where no motivation work is needed. What we’re talking about here is the next step that’s going to take some kind of effort or attention from you.

This approach separates choosing something to do from actually having to do it, which also combats anxiety. Since considering all the things you might have to do can be a source of stress, and since getting yourself to do something difficult can also be a source of stress, taking the two separately can make each piece easier to deal with.

Some examples of choosing the next step: If you’re writing, it might be starting the next chapter, or planning out the next piece of the outline, or editing a particular section; if you’re working on fitness, it might be exercising in the evening, or planning your next meal; if you’re organizing your home, it might be the next area you plan to clean up, or the next habit you need to practice; if you’re quitting smoking, it might be simply restocking your supply of gum or reading up on emphysema. Regardless, always knowing your next step keeps you literally one step ahead.

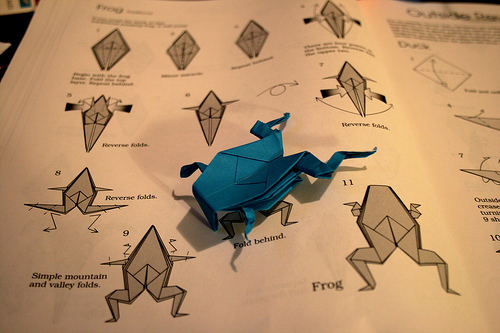

Photo by Tojosan