This series of articles on distraction is adapted from my eBook on Writing Motivation. In the first article in the series, I talked about the high cost of distractions and mentioned four things we can do to minimize them. This article follows up by discussing the first of those four, choosing your location.

Location, location, location

To the extent that you have some control over the times and places when you are focusing on a goal you’re trying to achieve (like getting your finances in order, learning a language, or writing a book), good choices of working environment will help you work better and with fewer interruptions.

We don’t always consider the power a location can have to minimize distractions, but once we do, the kinds of locations are fairly self-evident: favor locations where there will be few distractions, and try to avoid places where you might run into friends or be expected to respond to people or events. The most accessible and convenient locations–your home or usual workplace–are often the most vulnerable to distractions because people will expect to find you there. But places where you’re less likely to be distracted, like a friend’s spare room or the library (when those kinds of places are options in the first place), often involve extra time and effort to reach, and therefore may discourage work on your goal or cut into your productive time.

While there’s no way around being bound to a location for some efforts, like decluttering, avoid being completely dependent on one location if possible: the more times and places you can use to work toward your goal, the more progress you’re likely to make.

To the extent that you have a choice, try to prefer working on your goal at times when you’ll have minimal distractions, as long as those times don’t offer other problems—for instance, late at night can be a peaceful and productive time to work, but not if you’re always exhausted by then, or if it will have a serious effect on you getting enough sleep, or if your work would wake somebody up.

Sometimes it’s possible to get more uninterrupted time to work on your goal by shifting around more interruptible activities, like housecleaning.

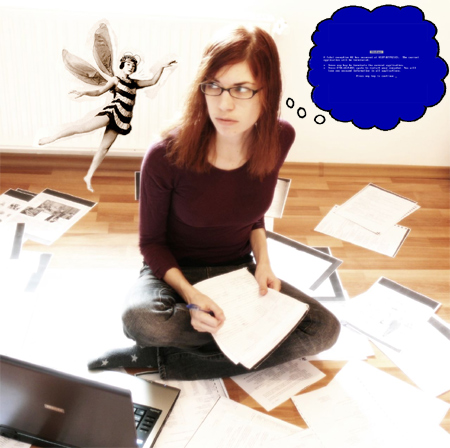

Mental work environment

Your mental work environment is also a key factor. You can prepare your brain by committing to the project you’re about to work on and setting a minimum amount of time to focus on it. Avoid shifting around among different kinds of tasks within one work session when possible–for instance, working a little on your business plan, then answering some correspondence, then coming back to the business plan–since when you make these shifts you’re effectively interrupting yourself.

In the next article in this series, we’ll dig into the other three strategies for minimizing distractions: managing responsibilities, making rules, and erecting barriers.

Photo by girolame