I recently wrote an article on motivation for academic writing, an especially tough area, and it now appears on the academic writing site PhD2Published: “The Will to Write: Getting Past the 6 Most Common Obstacles.” The site posts daily articles to encourage and support the process of writing dissertations, papers, theses, monographs, etc.

You don’t have to delay gratification or help other people to be human. Not delaying gratification can lead to a lot of suffering, and not helping others can lead to loneliness and insecurity, but they’re not strictly necessary.

To some extent, though, the better we are at delaying gratification and helping others out, the more we start experiencing benefits out of the blue. Being a dependable and altruistic member of a community creates a network of people who are willing to do things for us, look out for our interests, lend us assistance when we most need it, and support us when we’re recovering from a loss or setback. Handling our own desires intelligently has a similar effect: we continue to reap benefits from things we’ve done in the past.

Yet both helping others and delaying gratification pose a problem: we have to give things up now with a chance that we won’t be paid back. For instance, if I have a box of fudge and I hold off on eating some or all of it, I have to give up the experience of eating the fudge right now and run the risk of someone else eating the fudge, of losing it, of it going bad, etc. The surest way to get all of the “benefit” from eating the fudge is to consume all of it, right away.

The problem with that approach is that taking everything you can get the moment you have it often leads to a cornucopia of troubles. In the case of the fudge, eating a lot of it at once can make a person sick, contribute to unwanted weight gain, create an unpleasant sugar rush and crash, and cause the person to look like a pig to onlookers. To eat all of the fudge, I don’t have to give anything up, but in the end I bring on suffering and fail to experience the same kind of satisfaction I’d get from managing the fudge over time.

In a similar way, if I have a pound of fudge and some people I could share it with, the surest way to get all of the “benefit” of the pleasure of eating the fudge is to eat it myself, whether I do that now or later. Yet sharing the fudge with others makes others more likely to share with me, and over time is likely to yield a variety of benefits that a pound of fudge alone could not confer—especially if I don’t want to eat a whole pound of fudge.

Evolving as individuals, becoming more enlightened and compassionate, and learning how to handle ourselves better therefore means a lot of saying “I’m going to give up on this pleasure I could get right at the moment” and “I’m going to give up on this surer thing for this more uncertain thing.” It’s counterintuitive, and to a large extent we’re not built for it, and yet our lives become much happier the more we learn to defer and share. We can’t experience the pleasure our future selves will experience when we set things by for them now, or directly experience the pleasure others feel when we do things on their behalf. Fortunately, we can experience the immediate goodwill we call forth when we do things for other people and the satisfaction we get from making good choices. While these things don’t give us the immediate animal response we’d get from eating a pound of fudge, they also tend to make us feel healthier, happier, and in better harmony with our lives and environments–rather than making us sick.

If you’re interested in this topic, you may enjoy reading my article “The Difference Between Pleasure and Happiness.”

Photo by Xiangdian

In celebration of Thanksgiving, here’s a short story in honor of the brave and often delicious turkey, originally published at The Daily Cabal. If this whets your appetite, there are 172 more very short stories of mine in the collection Bam! 172 Hellaciously Quick Stories.

“OK, I respect that,” I said to the other turkey, “but if we’re going to have a conversation, I need to give you some kind of name. Why don’t I call you Lashonda?”

“OK, I respect that,” I said to the other turkey, “but if we’re going to have a conversation, I need to give you some kind of name. Why don’t I call you Lashonda?”

“Gobble,” said Lashonda.

A chubby guy in rubber gloves and a rubber apron snatched me up by the feet and hung me upside down.

“Hi!” I said in Turkey, but of course he didn’t understand.

A second later he hung Lashonda up next to me, and we swung gently from side to side as the track we were hanging from carried us into the gloom.

“This feels strangely peaceful,” I said. “Who would’ve imagined? Hanging upside down … it’s so relaxing. It’s a little like grooming. I had an incarnation as a spider monkey once, and we were always grooming each other. Most relaxing thing in the world.”

Up ahead, there was a burst of gobbling that was abruptly cut short. The machine we were swinging from made a gentle creak-creak sound.

“Gobble gobble,” said Lashonda.

“You know, it’s funny you should mention that,” I said. “That’s what I’ve been wondering about: why a turkey in the first place? I mean, we’re raised butt-to-wattle in a pen, fed terrible food, and eventually carted off to be slaughtered. What’s the point in that kind of existence? I’m worried that if I don’t learn anything from this life, I’ll just have to do it all over again.”

We came around a bend, and I saw that the line dipped, lowering turkey heads into a silvery machine. There was an electrical noise somewhere.

“It’s not the same as being a wild creature or a human or whatever,” I said. “As those you can make choices. But what can you possibly learn if you don’t get to make any actual choices?”

Lashonda was silent. I wondered if she was scared.

“I’m probably overthinking it,” I said. “Right now, I just feel grateful, you know? Grateful to be hanging upside down, grateful to have a friend like you right when I need one … I don’t think I’ve ever told you, Lashonda, in the few minutes we’ve known each other, how much I appreciate your company and your level-headed attitude.”

The line began to descend, and all of a sudden the silvery machine was right in front of me.

“Have a nice life, Lashonda,” I said. Then something sparked.

Photo by cyanocorax

My short story “Keeping an Eye Out for the Time Police Regardless” is up today at Every Day Fiction, where a new short story appears each morning. There’s an engaging community of readers and commenters on the site, leading to a discussion in the comments that pointed out at least two possible interpretations of the story I hadn’t even considered and gave great insight into what worked better and didn’t work as well in the piece.

There’s a recent post on the Psychology Today site entitled “The Science of Rick Perry’s Brain Freeze,” in which psychologist Ira E. Hyman attempts to explain how a governor of Texas and presidential candidate could have had trouble remembering the Department of Energy, obvious jokes aside.

There’s a recent post on the Psychology Today site entitled “The Science of Rick Perry’s Brain Freeze,” in which psychologist Ira E. Hyman attempts to explain how a governor of Texas and presidential candidate could have had trouble remembering the Department of Energy, obvious jokes aside.

You may be pleased, annoyed, or uninterested to read that Dr. Hyman thinks Perry’s gaffe isn’t an indication of stupidity, but I’m guessing you’ll come away from the article happy based on the following potentially helpful tip. In it, he refers to the problem of “blocking,” a situation in which our brain has so much related information readily available that the specific piece of information needed can’t be found in the pile. Dr. Hyman says:

In cases of blocking, a brief period of thinking about something else may be enough to remove the block. In essence, you remove the competitors from active thought and then the next attempt to retrieve the information works more effectively.

I haven’t had the opportunity to try this yet, but you can bet I will next chance I get. If you try it, or have other tricks, I’d love for you to post in comments, below.

Photo by Dr Craig

In a recent comment to my post “How Do You Fix Greed? Part II: American Society Is Built for Greed,” someone asked

Why should l sacrifice my self to others? Read Ayn Rand, and you will know where greed comes from.

I was surprised by the question, because the answer seemed obvious to me, but the more I thought about the response, the more grateful I am for the comment, because it’s a fair question: even if greed is bad for society, which is something I’ve been asserting in recent posts, from a certain perspective there’s the following pressing question: So what? If I can get everything I want, why should it matter to me if other people are unhappy about that, or if it interferes with things society or culture expects from me?

For the asker’s interest, I’ve read Ayn Rand, and I’m familiar with a lot of arguments for greed. If you’re looking at the question on a strictly personal level, it comes down to this: people who let themselves fall prey to their own greed are assuming that getting more will bring them more pleasure, and that pleasure and happiness are the same thing. The truth–and there’s good science backing this up–is that having more stuff does not necessarily bring more pleasure, and that even if it did (which it doesn’t, remember), that pleasure doesn’t by itself amount to happiness.

I’m not going to go into detail about all the research here, to prevent this post from becoming unmanageably long, but before I continue I’ll link to other articles on this site, several of which reference the studies that provide the raw information for the connections between human relationships, happiness, and pleasure that I’m about to describe.

The Difference Between Pleasure and Happiness

If It’s Not Fun, Why Do It? A Few Pointed Answers

Why Happiness Is Key

How Other People’s Happiness Affects Our Own

Want to Reduce Stress? Increase Social Time

The Best 40 Percent of Happiness (this one covers lottery winners)

The High Cost of Not Liking Your Job

Why doesn’t “more” bring more pleasure?

Getting more things does not necessarily lead to more pleasure, although it’s true that some things, in some situations, can add to pleasure and even happiness. Unfortunately for our pleasure levels, though, the more we get, the less any given part of it matters. If you go to a restaurant and eat the most delicious meal in the world, the first time you eat it, you may be in ecstasy. If you eat it again the next day, due something psychologists call “hedonic adaptation,” it simply won’t be as good. It’s similar to the process a drug addict may go through, whether that drug is caffeine or crack or something in between. The first hit has an enormous effect, but subsequent experiences produce less and less dopamine, the neurochemical that makes us feel pleasure. In other words, the more I have, the less pleasure I get from each thing.

Additionally, having more power, money, resources, or things also means I have more concerns, because I need to defend myself from people who want to usurp my power, siphon off my money, use my resources, or take my things. As I get more and more, what I have pleases me less and adds more to my stress load. We often envy celebrities, people with political power, and others who have “more,” yet the rates of scandal, failed marriage, substance abuse, and other indicators of severe unhappiness seem to be exceptionally high among these kinds of people. Some of it is surely the pressure of being in the public eye all of the time, but regardless, it lends support to the point that having more is not necessarily pleasurable. Ask the many people who’ve won the lottery and later committed suicide–oh wait, you can’t: they’re dead.

Isn’t “happiness” just another word for “pleasure”?

Even the pleasure that we can get from having more doesn’t amount to happiness. Happiness, according to research, has a lot to do with having enough and not much to do with having extra. It also has a lot to do with how we think and feel about ourselves and about our relationships with other people. If I feel like a good person, am proud of my accomplishments and integrity, enjoy the company of people close to me, experience trust and connection with others, and otherwise make the most of myself and my relationships, I’m far, far more likely to be happy than if I have piles of stuff, people whose interest in me might be mainly about my having piles of stuff, and things I don’t need that I have to defend from people who either don’t have enough stuff or are as greedy as I am.

Greed at its heart is a misunderstanding, at attempt to substitute money, power, or stuff for the things that really make us happy (see the first article in this series, “How Do You Fix Greed? Part I: The Roots of Greed“). The altruistic and kind behavior that seems like sacrificing ourselves, when done in a healthy and proportionate way, surprisingly turns out to get us the most individual happiness of anything we could possibly do. Greed is an easy path to falling short of the happiness we could otherwise achieve.

Photo by CaptPiper

Sandra Tayler, a friend from Codex, recently posted her reasons for sticking to a large extent with paper books over eBooks. While she has a much different take than I do on the issue, she makes some very meaningful points, and I especially like her ideas about children’s books, which she makes better use of than many of us parents. You can read her thoughts on the matter at http://www.onecobble.com/2011/11/05/kindle-update-why-i-still-buy-paper-books/.

Sandra Tayler, a friend from Codex, recently posted her reasons for sticking to a large extent with paper books over eBooks. While she has a much different take than I do on the issue, she makes some very meaningful points, and I especially like her ideas about children’s books, which she makes better use of than many of us parents. You can read her thoughts on the matter at http://www.onecobble.com/2011/11/05/kindle-update-why-i-still-buy-paper-books/.

Photo by altopower

The process of writing has changed enormously in the past 50 years. Word processors transformed writing from something you have to redo every time you want to make changes to something that can include any number of changes with no extra effort beyond the edits themselves. The Web has elevated research from a limited, time-consuming, and sometimes expensive process into a few minutes communing with Google. Laptops and similar devices have taken these improvements out on the road. Print on demand and especially eBooks have opened an entirely separate career path for some independent writers.

In comparison to these game-changing tools and resources, what difference does Scrivener make? Well, if you’re like about 80% of writers, the answer used to be “none at all,” because Scrivener was originally a Mac-only program. Unless you’ve been beta testing the Windows version, all that changed yesterday when Scrivener 1.0 for Windows was introduced.

What’s so great about Scrivener?

I originally posted about Scrivener in an article called “How Tools and Environment Make Work Into Play, Part I: The Example of Scrivener.” My main point in that article was that for long or complex writing projects–novels, screenplays, stage plays, non-fiction books, articles with lots of information, or even short stories with especially detailed worlds or plots–Scrivener takes the heavy lifting out of organizing a lot of thoughts, resources, research, ideas, plot points, facts, scenes, or other details into a living outline that naturally evolves into your actual book.

For example, when I wrote my short book The Writing Engine: A Practical Guide to Writing Motivation (available in PDF form for free on this site, or for 99 cents on Amazon for the Kindle), I had an enormous number of tips, tricks, insights gleaned from scientific research, anecdotes, and whole articles to organize into a well-structured book. Using Scrivener, I dumped everything in without worrying about the order and then was easily able to organize it all into a structure that I could write and rewrite my way through until I had a clean final draft. While organizing, I was able to focus on just a few elements at a time, which took away that crazy, overwhelmed feeling of worrying that I’d forget some important piece of information. Once I began my actual writing, it also allowed me to focus singlemindedly on what I was writing.

How does Scrivener work?

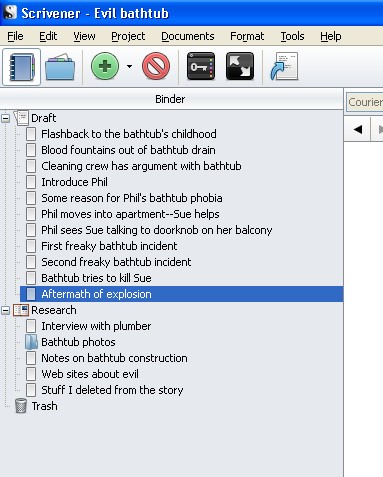

The basic idea behind Scrivener is very simple: it conceives of a piece of writing as a bunch of pieces of text, each of which might be a paragraph, a scene, a chapter, an illustration, some research material, notes for your reference, etc. These pieces are organized into two general categories: Draft (for the writing itself) and Research (for supporting material that’s not intended to wind up in the actual book).

All of these pieces can be organized into an outline. For instance, I might start with these ideas for an evil bathtub story:

Note that in this picture I’m just showing the “binder,” the section on the left where I come up with the pieces I want to organize. I typed the names of my pieces right into there. I also could have started with some material I’d already written, which would go into the text area on the right that appears as I click on each item.

As you can see, I’m starting with some ideas about characters, a few plot points, some incidents, and some research. I’m not sure what happens when yet: all I have is glimpses of what’s happening in a short story about an evil bathtub.

(It’s ironic to me that I had forgotten, in putting together this example, that in college I actually wrote a story in college about a cursed bathtub. I guess this is a thing with me. I think the title was “Miriam Pzicsky and the Handyman from Hell.” I’m pleased to say that I have improved as a writer somewhat since college.)

In the next picture, you’ll see what I did with those pieces of information: I chose to impose three-act structure (something I don’t have to do and generally don’t do explicitly) and then dragged the items around into something resembling an order for the story. One of the great things about Scrivener is that in doing this, I automatically begin to see where there are holes in the story, where it might get repetitive, and what kind of structure I’m dealing with. Just seeing the story as an outline helps me improve the story.

Once I’m done adding or changing elements in my outline, I’ll just start clicking on items in it and writing those items one by one. I can add, delete, and move around pieces as I write (which is why I refer to this as a “living outline”), and the click-and-write experience makes it easy to focus on one part of the piece at a time.

Scrivener has many, many more useful features. This glimpse is only meant to show what I think is the key useful concept behind the program. Fortunately, it’s more than a concept: the software has been developed with a lot of appropriate, productive, and easy-to-use features.

While Scrivener is useful, it’s also fun, at least for me. When I use Scrivener, I use less of my attention to keep track of details and more of it to write. This makes me a happier writer.

When is Scrivener not useful?

Scrivener isn’t for everyone. If you like to start writing a piece from the beginning and then go right through to the end, or if you tend to make a traditional outline just to get a grip on what you’re doing and then don’t do much with that outline except consult it as you write, I’m not sure Scrivener would be especially helpful for you. If you write off the cuff, without research or planning, there won’t be much Scrivener can help you organize. Personally, I love Scrivener’s organizational features, but I rarely use it for short stories: I find it much more useful for outlined novels and non-fiction projects.

Even if you write by the seat of your pants, though, you may find Scrivener invaluable. You can start writing a novel by typing “Chapter 1” and plunging ahead with only the most general sense of where you’re going, but even in that kind of situation you will probably start coming up with scenes you want to include later, plot developments that need to occur, bits to insert into what you’ve already written, research materials, and more things to be organized. Scrivener doesn’t care whether you organize before, during, or after writing: it just helps you get everything into a usable structure.

If I’ve piqued your interest

The fine folks at Literature and Latte offer a free, 30-day trial which is in fact far better than most 30-day trials in that it doesn’t count calendar days, but instead days you use Scrivener. If you use it twice a week, your 30-day trial will last you 15 weeks. You also don’t have to create an account, sign up for anything, or even supply an e-mail address to get the trial. You can download it here: http://www.literatureandlatte.com/scrivener.php .

If you do opt to buy, the price is $40, but there’s a 20% discount you can find at http://www.literatureandlatte.com/nanowrimo.php . A 50% discount is available for people who “win” NaNoWriMo, completing at least 50,000 words of a novel project in the month of November. (For more info on NaNoWriMo, go to http://www.nanowrimo.org/ .)

This came as a surprise: today Amazon announced they are starting a free lending library for Kindle owners who have an Amazon Prime membership. Amazon Prime has to be one of the most unlikely bargains out there. Who thought of putting streaming movies, free shipping, and temporary eBook access together in one package (for $79 a year)? Counterintuitive or not, it’s an attractive option if you order a lot of things on the Web.

Even if you do already own a Kindle and have Amazon Prime, don’t plan on suddenly being able to read whatever you want for free. Amazon is only offering a limited number of books under the program, with a maximum of one loan per month per Prime member. With that said, though, there’s an impressive array of books available–more than 5,000 of them, including some current bestsellers.

I continue to worry about the fate of libraries as eReading spreads and the eBook world becomes more flexible and friendly to readers. Post your comments, links to articles elsewhere on the Web, or links to your own blogging on the subject below.

Today is the 144th anniversary of the birthday of Marie Skłodowska-Curie, a woman who won two Nobel prizes in different disciplines: Physics (in 1903, with her husband Pierre and a third scientist) and Chemistry (in 1911, by herself). In and among many other accomplishments–for her family and for her native Poland, for example–she managed to simultaneously drive the dawning of a greater level of respect for women in general and to make paradigm-changing discoveries in science.

Today is the 144th anniversary of the birthday of Marie Skłodowska-Curie, a woman who won two Nobel prizes in different disciplines: Physics (in 1903, with her husband Pierre and a third scientist) and Chemistry (in 1911, by herself). In and among many other accomplishments–for her family and for her native Poland, for example–she managed to simultaneously drive the dawning of a greater level of respect for women in general and to make paradigm-changing discoveries in science.

I would like to be able to comment on what drove Skłodowska-Curie, but without a lot more research, my comments would be too little observation and too much speculation. What I do know is that she seemed driven to better her understanding of science and to accomplish much else of value from an early age. Based on research on both intelligence and temperament, it seems likely she maximized some benefits she was born with in both areas: a sharp mind and emotional resilience.

I mention resilience because Skłodowska-Curie didn’t have an easy time of it in childhood. She did benefit from a highly educated and supportive family, but it was a family that suffered a series of painful losses as Marie was growing up: her eldest sister, Zofia, died of typhus when Marie was ten, and her mother died of tuberculosis when Marie was twelve.

Both sides of her family had been wealthy, but both had worked for Polish independence from the Russian empire and had been stripped of their wealth, so getting a decent university education was a significant struggle for Marie. While as a young woman, she worked as a governess to earn money to be able to attend university and to support her sister doing so in Paris. At this point she fell in love with a young and brilliant mathematician, but his family rejected her because of her poverty.

We all react differently to loss and adversity, whether it is our country being dominated by a tyrannical neighboring empire, the death of friends and families, being kept from the ones we love, or being frustrated in our attempts to accomplish our goals in life. It’s easy sometimes to retreat into self-pity, complaining, giving up, becoming hard and cynical, compromising our visions of what our lives could be, taking the next easy situation that comes along even if it’s wrong for us … but Marie did none of these, which makes her birthday more than a historical note: it can, if we like, become a day on which we’re inspired to let our setbacks, disappointments, and losses fuel our commitment to doing great things in the world.

If you enjoyed this post, you might be interested in reading “Do You Have Enough Talent to Become Great At It?” and “Randall Munroe and Zombie Marie Curie on Greatness.”