A recent post on Lifehacker, “Work Less and Do More by Applying the Pareto Principle to Your Task List,” reminds us of an idea that could be the secret to enormous productivity or just another mirage. Perhaps it’s a revelation for some people and a waste of time for the others. I’m talking about the Pareto Principle.

Pay 20, get 80?

The Pareto Principle is the idea that 80% of the useful results we get in life arise from only 20% of our efforts. It’s a tantalizing idea, and it seems to apply to a lot of different situations. It’s named after Vilfredo Pareto, an Italian economist who noticed that 80% of Italy’s land was owned by 20% of its population. It seems to apply to much more than economics, though, having cropped up in business, health care, software engineering, investing, criminology, and elsewhere. Some research even suggests that it’s a sort of naturally emerging dynamic, something that arises on its own in the natural world.

And yet … your mileage may vary. Is everybody on approximately the same level of inefficiency? Do we all prioritize the same way?

For a parallel, consider Stephen King’s usual approach to writing: he generates a rough draft without being concerned too much about having some sections that don’t pull their weight, but then edits to cut out about 10%. Contrarily, a number of pro writers I know typically see their work expand when they edit it, and often this is a significant improvement.

Wait a minute …

Even setting aside individual differences, I’m dubious about the Pareto Principle being a basic law of the universe. For example, let’s look at traditional employment: does 80% of the income come from 20% of the work time? Absolutely not. It could be argued that in some cases 80% of the benefit to the company comes from 20% of the work performed, but even that only holds up in special circumstances. It doesn’t for teachers, for instance, who in addition to passing along knowledge also provide an environment and structure in which kids can ideally grow and learn throughout the school day. It doesn’t apply to assembly line workers, or to farmers. In fact, the kinds of work where it seems to apply are the ones that are mainly about making choices and not much else. Maybe 80% of your investment income comes from 20% of your investments. Maybe 80% of your published writing comes from the best 20% of your writing ideas. Perhaps 80% of your impact as a middle manager at a widget manufacturing concern comes from 20% of your efforts. Elsewhere, it gets iffy.

And we can’t make good decisions all the time. While I certainly agree with focusing on the most important tasks and on the most impactful decisions, it hasn’t seemed to be the case in the world that people know which of their efforts will pay off in advance–and even when they do, they often have a lot of hard work to do to get to that payoff.

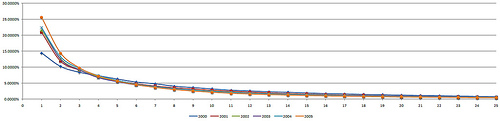

An example that refutes by agreeing

For example, this blog currently gets an average of something over 13,000 views per month. It’s certainly true that a small number of my posts are responsible for most of the search hits on the site: for example, “24 Ways to Stop Feeling Hungry” accounts for a big percentage of those 13,000-odd views. It’s also true, however, that the prominence of “24 Ways to Stop Feeling Hungry” on search engines is based in part on the general popularity of the site and the number of links to it from other places on the Internet, and those factors in turn are based on the hundreds and hundreds of posts I’ve written and published over the years this blog has been online.

So Pareto adherents might point to my blog and say “Look, this one post is responsible for a huge percentage of your visits” without understanding that that post alone would be little use without the rest of the site to support it.

To take another example, consider the non-fiction book contract I once got through the agent I got through the writing group I established from people I met attending two writing workshops. Where was the wasted time there? The writing workshops? The writing group? Getting the agent? Writing the book? I’m thinking the answer is “none of the above.”

To put it more simply and pragmatically: a lot this stuff is connected. Should we busy ourselves blindly with trivia day in and day out in hopes that it will all amount to something? Hell, no. On the other hand, we can’t get far by cherry-picking among our own efforts and trying to stick to only those with big payoffs. A sustainable, rewarding life is built on a lot of little payoffs, with big payoffs helping out now and again. The 20% of our efforts that seems to be making the biggest difference in our lives doesn’t stand alone.

Prioritization is the point

With that said, though, I think there’s a valuable point in the Pareto Principle material: it’s well worth comparing how much effort we’re putting in to how much value we think that effort creates. If you spend hours each day doing social media for your business but barely get a trickle of customers from that, are you doing it because you think over time it will build up to become a major asset to your business, or simply because people keep saying everyone ought to do social media? If I do writing exercises every morning instead of working on saleable material, is that necessarily helping my writing so much that it’s worth the lost opportunities?

What about you? Do you see a lot of 80/20 opportunities in your life? Or does the Pareto Principle not seem to hold water for you?

Graphic by igrigorik

I suppose it was 20 years ago or more that I read Brooks’ Sword of Shannara. I found it to be an unrepentant rip-off of Lord of the Rings. I had no writing aspirations at the time, but after reading that disaster, I thought “Well, anyone can write a book.” And then it was a short step to “I can write a book.”

I suppose it was 20 years ago or more that I read Brooks’ Sword of Shannara. I found it to be an unrepentant rip-off of Lord of the Rings. I had no writing aspirations at the time, but after reading that disaster, I thought “Well, anyone can write a book.” And then it was a short step to “I can write a book.” Poe. I started reading him when I was seven, while those moronic learn-to-read first-grade textbooks were being stuffed down my throat. Death from boredom…. I never wanted to learn to read–I wanted to be outside doing things. My dad tried to teach me starting at age four, and I despised it. Then elementary school almost murdered me with dreariness. Squash, crush, stifle. Man, did Poe revive me. The way he used language! By the time I was ten, I’d read all the fiction and poetry he ever wrote. I used to think the word, “poetry,” came from his name. He taught me to use words to give the world hard edges. He started me writing stories because stories gave my strapped-down childhood a shape I could control. I was a child, I wasn’t allowed to do real things, I wasn’t free, so I wrote. I still write to give the world hard edges, to be free. Poe was the first writer to save my life. I honor him.

Poe. I started reading him when I was seven, while those moronic learn-to-read first-grade textbooks were being stuffed down my throat. Death from boredom…. I never wanted to learn to read–I wanted to be outside doing things. My dad tried to teach me starting at age four, and I despised it. Then elementary school almost murdered me with dreariness. Squash, crush, stifle. Man, did Poe revive me. The way he used language! By the time I was ten, I’d read all the fiction and poetry he ever wrote. I used to think the word, “poetry,” came from his name. He taught me to use words to give the world hard edges. He started me writing stories because stories gave my strapped-down childhood a shape I could control. I was a child, I wasn’t allowed to do real things, I wasn’t free, so I wrote. I still write to give the world hard edges, to be free. Poe was the first writer to save my life. I honor him.

I first tried writing for publication after reading Marion Zimmer Bradley’s Sword & Sorceress series. I commented to my husband that it would be such fun to write for something like that, and he encouraged me to give it a try. S&S was invitation-only by then, and shortly thereafter MZB died and the series ended. By then, though, I’d had a story accepted by The First Line, and I was hooked.

I first tried writing for publication after reading Marion Zimmer Bradley’s Sword & Sorceress series. I commented to my husband that it would be such fun to write for something like that, and he encouraged me to give it a try. S&S was invitation-only by then, and shortly thereafter MZB died and the series ended. By then, though, I’d had a story accepted by The First Line, and I was hooked.