This is the second article in a series on anger. The first article was Monday’s “Anger: Does Venting Help or Just Make It Worse?“

One of the tricky things about dealing with anger is that our immediate mental response system for dealing with threats–run by a primitive part of the brain called the amygdala–doesn’t wait for us to understand what’s going on. This is pretty reasonable: if you’re a primitive human being and you’re being attacked by a Smilodon, you don’t want to be thinking about whether to react or not: you want to be immediately jabbing with your spear or running away (fight or flight). This is why people can be startled even by things that they know intellectually aren’t dangerous, like a loud noise in a carnival haunted house.

But Smilodons are extinct these days, and while the fast-track fight or flight response is still useful sometimes, as when we jump out of the way of a falling object, at other times anger and fear responses are very bad news. For instance, if someone is scared or upset and says something ill-considered to us, we may have a hard time not immediately responding in kind and turning a offhand comment into an argument.

Yet we do have the power to override our amygdala-driven gut reactions, and two of our best weapons in this fight are preparation and self-awareness.

Preparation in this case means putting ourselves in a mood to defuse instead of magnify negative feelings. One of the best ways to do this, notes Daniel Goleman in his book Emotional Intelligence, is to look at people toward whom you may be feeling angry “with a more charitable line of thought,” which “tempers anger with mercy, or at least an open mind, short-circuiting the buildup of rage.” In other words, thinking about what circumstances may be driving people to do things we don’t like rather than focusing on our mental condemnation of those people for doing those things creates an opportunity for compassion and keeping our cool.

As for self-awareness, this is an approach I’ve praised in other articles, such as “Mindfulness and Deer Flies.” Being aware of our own emotions gives us the opportunity to do something about a situation using our thoughts, for instance by noticing and repairing broken ideas. Lack of self-awareness–that is, acting without considering why we’re acting or what we’re feeling–closes off that option to us completely. When we’re not aware of our own emotions, we are mostly slaves to our own emotional habits.

This series will continue in the next week or two with more information about and strategies for dealing with anger.

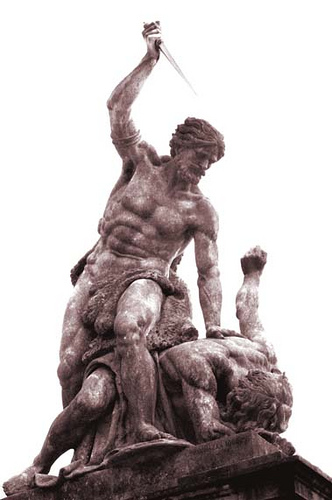

Photo by euthman