The process of writing has changed enormously in the past 50 years. Word processors transformed writing from something you have to redo every time you want to make changes to something that can include any number of changes with no extra effort beyond the edits themselves. The Web has elevated research from a limited, time-consuming, and sometimes expensive process into a few minutes communing with Google. Laptops and similar devices have taken these improvements out on the road. Print on demand and especially eBooks have opened an entirely separate career path for some independent writers.

In comparison to these game-changing tools and resources, what difference does Scrivener make? Well, if you’re like about 80% of writers, the answer used to be “none at all,” because Scrivener was originally a Mac-only program. Unless you’ve been beta testing the Windows version, all that changed yesterday when Scrivener 1.0 for Windows was introduced.

What’s so great about Scrivener?

I originally posted about Scrivener in an article called “How Tools and Environment Make Work Into Play, Part I: The Example of Scrivener.” My main point in that article was that for long or complex writing projects–novels, screenplays, stage plays, non-fiction books, articles with lots of information, or even short stories with especially detailed worlds or plots–Scrivener takes the heavy lifting out of organizing a lot of thoughts, resources, research, ideas, plot points, facts, scenes, or other details into a living outline that naturally evolves into your actual book.

For example, when I wrote my short book The Writing Engine: A Practical Guide to Writing Motivation (available in PDF form for free on this site, or for 99 cents on Amazon for the Kindle), I had an enormous number of tips, tricks, insights gleaned from scientific research, anecdotes, and whole articles to organize into a well-structured book. Using Scrivener, I dumped everything in without worrying about the order and then was easily able to organize it all into a structure that I could write and rewrite my way through until I had a clean final draft. While organizing, I was able to focus on just a few elements at a time, which took away that crazy, overwhelmed feeling of worrying that I’d forget some important piece of information. Once I began my actual writing, it also allowed me to focus singlemindedly on what I was writing.

How does Scrivener work?

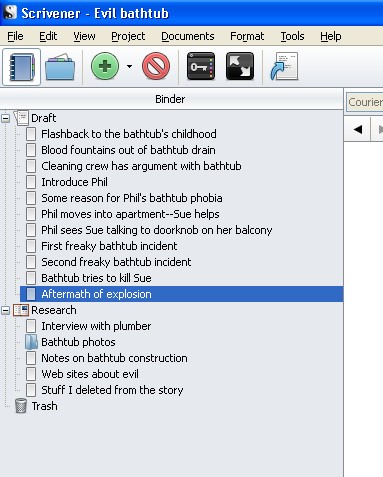

The basic idea behind Scrivener is very simple: it conceives of a piece of writing as a bunch of pieces of text, each of which might be a paragraph, a scene, a chapter, an illustration, some research material, notes for your reference, etc. These pieces are organized into two general categories: Draft (for the writing itself) and Research (for supporting material that’s not intended to wind up in the actual book).

All of these pieces can be organized into an outline. For instance, I might start with these ideas for an evil bathtub story:

Note that in this picture I’m just showing the “binder,” the section on the left where I come up with the pieces I want to organize. I typed the names of my pieces right into there. I also could have started with some material I’d already written, which would go into the text area on the right that appears as I click on each item.

As you can see, I’m starting with some ideas about characters, a few plot points, some incidents, and some research. I’m not sure what happens when yet: all I have is glimpses of what’s happening in a short story about an evil bathtub.

(It’s ironic to me that I had forgotten, in putting together this example, that in college I actually wrote a story in college about a cursed bathtub. I guess this is a thing with me. I think the title was “Miriam Pzicsky and the Handyman from Hell.” I’m pleased to say that I have improved as a writer somewhat since college.)

In the next picture, you’ll see what I did with those pieces of information: I chose to impose three-act structure (something I don’t have to do and generally don’t do explicitly) and then dragged the items around into something resembling an order for the story. One of the great things about Scrivener is that in doing this, I automatically begin to see where there are holes in the story, where it might get repetitive, and what kind of structure I’m dealing with. Just seeing the story as an outline helps me improve the story.

Once I’m done adding or changing elements in my outline, I’ll just start clicking on items in it and writing those items one by one. I can add, delete, and move around pieces as I write (which is why I refer to this as a “living outline”), and the click-and-write experience makes it easy to focus on one part of the piece at a time.

Scrivener has many, many more useful features. This glimpse is only meant to show what I think is the key useful concept behind the program. Fortunately, it’s more than a concept: the software has been developed with a lot of appropriate, productive, and easy-to-use features.

While Scrivener is useful, it’s also fun, at least for me. When I use Scrivener, I use less of my attention to keep track of details and more of it to write. This makes me a happier writer.

When is Scrivener not useful?

Scrivener isn’t for everyone. If you like to start writing a piece from the beginning and then go right through to the end, or if you tend to make a traditional outline just to get a grip on what you’re doing and then don’t do much with that outline except consult it as you write, I’m not sure Scrivener would be especially helpful for you. If you write off the cuff, without research or planning, there won’t be much Scrivener can help you organize. Personally, I love Scrivener’s organizational features, but I rarely use it for short stories: I find it much more useful for outlined novels and non-fiction projects.

Even if you write by the seat of your pants, though, you may find Scrivener invaluable. You can start writing a novel by typing “Chapter 1” and plunging ahead with only the most general sense of where you’re going, but even in that kind of situation you will probably start coming up with scenes you want to include later, plot developments that need to occur, bits to insert into what you’ve already written, research materials, and more things to be organized. Scrivener doesn’t care whether you organize before, during, or after writing: it just helps you get everything into a usable structure.

If I’ve piqued your interest

The fine folks at Literature and Latte offer a free, 30-day trial which is in fact far better than most 30-day trials in that it doesn’t count calendar days, but instead days you use Scrivener. If you use it twice a week, your 30-day trial will last you 15 weeks. You also don’t have to create an account, sign up for anything, or even supply an e-mail address to get the trial. You can download it here: http://www.literatureandlatte.com/scrivener.php .

If you do opt to buy, the price is $40, but there’s a 20% discount you can find at http://www.literatureandlatte.com/nanowrimo.php . A 50% discount is available for people who “win” NaNoWriMo, completing at least 50,000 words of a novel project in the month of November. (For more info on NaNoWriMo, go to http://www.nanowrimo.org/ .)