Which is better, between literary and commercial fiction? Maybe we can agree that the answer depends not just on each individual’s tastes but also on the question better for what? Better for getting engrossed and transported? Better for empathizing with people living in tragic circumstances? Better for opening up ambiguous but important life questions?

Not long ago, a reader named Ankush commented on my article “7 Key Self-Motivation Strategies for Writers” with several questions, one of which–how writers can enjoy their work and not feel oppressed by it–I tackled in my recent post “Joy and Misery for Writers.” He opened a different can of worms with this question:

After much struggle, I’m beginning to feel that I’m more of a literary writer than genre writer. I think that genres are inherently repetitive, and the only scope of originality is in literary fiction. But the, perhaps I’m saying this to avoid facing my failures in genre writing (particular horror).

The basic concern here–which should I write, literary or commercial fiction?–is one that has come up for me in recent years too, and has probably (I’m guessing) been a pertinent one for most writers who ever spend time working on commercial/genre fiction.

Separating literary from commercial fiction

To be clear about my terms, by “commercial fiction” or “genre fiction” I mean fiction that tries to appeal to readers who are interested in stories with certain kinds of premises: mysteries, science fiction, fantasy, horror, romance, thrillers, and so on. By literary fiction, then, I mean fiction that asserts that the value in the story will come from the specific situation, quality of the writing, characters, description, etc. rather than anything general about the premise.

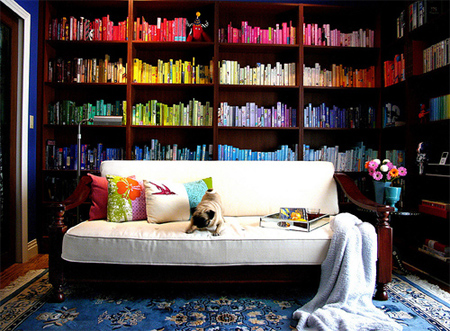

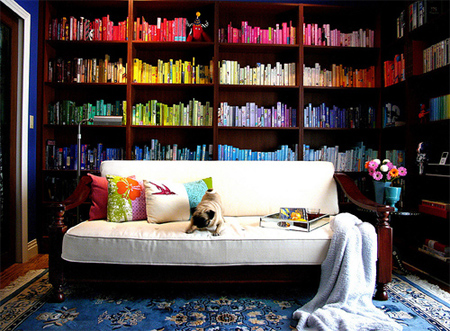

However, commercial fiction can have superlative writing, characters, description and so on; and literary fiction can written around a premise that could be categorized as romance (Jane Eyre), science fiction (1984, The Handmaid’s Tale), or another genre. In fact, there’s no hard delineation between the two groups at all, but the way they’re generally distinguished is how they try to appeal to readers and how they are sold. You will find these different kinds of books segregated in many bookstores and libraries, but not on many home bookshelves. For more on the perceived distinctions between commercial and literary, see my 2007 post “The Myth of the Science Fiction Ghetto.”

You can probably tell from the above that I’m not going to agree with Ankush’s point of view that genre fiction is inherently repetitive. You can’t tell me that Ender’s Game or The Golden Compass or Flowers for Algernon were just rehashes of work that had come before (OK, you can tell me–but I really won’t listen). There’s nothing stopping a genre novel from being just as fresh, insightful, revelatory, and subtle as the best literary fiction just because it’s about finding out who killed someone or because it has a spaceship on the cover.

Push vs. pull

So what am I saying is the real difference between commercial and literary? It’s not arbitrary that they’re sold to different readers with different approaches: there’s a difference in how they’re experienced. My contention is that this difference is about whether it’s the story’s job to pull in the reader or the reader’s job to dig into the story.

The thing about commercial fiction for those of us who enjoy it is that it’s effortless and entertaining to read. You don’t take a break from a good romance or fantasy novel halfway through because of emotional strain or intellectual effort. The tension in the story pulls you in, along with promises of trips to places you want to go, people you’re delighted to watch in action, and scenes of fascinating things unfolding. Commercial fiction can be intellectually and emotionally challenging, but successful commercial fiction uses tension, action, and wonder to keep readers immersed without any special effort on their part.

By contrast, literary fiction at its best seeks to be deep, multi-layered, and open-ended. It offers something that the reader can delve into, consider, argue with, or decide to become immersed in.

In good commercial fiction, it’s the author’s responsibility to pull in the reader. In good literary fiction, it’s the reader’s responsibility to find something of value in the book.

Shedding light on how people look at literary and commercial fiction

I’ll be quick to add that this distinction of the two isn’t cut and dried either. The only absolute way to call something commercial or literary is to look at how it’s sold, and the only use in doing that is knowing how to sell it. But I think looking at the issue as one of whether it’s the author’s or reader’s responsibility to lead the way sheds some useful light on how people view the two types.

A book that sucks the reader in and does everything it can to maintain interest could be accused of being simplistic, formulaic, or of pandering to the reader at the expense of a meaningful story. Some (not all) commercial fiction does pander, after all.

Literary fiction, on the other hand, could be looked on as boring or out of touch. If you start reading the book and it doesn’t grab you by the lapels and drag you into the story the way commercial fiction you enjoy does, you may conclude that the book isn’t well written or has nothing to offer you.

This also helps shed light on what’s going on with literary writers who shun action in their writing or who complain that readers are lazy: commercial fiction readers are expecting the author to come out and meet them, while literary authors are expecting the readers to come inside and look for them. If both stay in that mode, they’ll never meet, and the commercial fiction readers will wander off looking for more outgoing writers, while the literary authors give up on them and settle for the subset of readers who made a special effort. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing: no book is for all readers, and readers don’t have to like every kind of book. However, it’s useful to understand.

Which to write?

For writers, each approach has its attractions. Commercial fiction can ensnare more readers because it isn’t limited to those who are willing to put special effort into digging in. Literary fiction can trust that its readers will wait for the good stuff and structure its stories so that they maximize meaning and impact. Ideally your commercial fiction is so rich and rewarding that even readers who are pulled in are inspired to look deeper and think harder, or your literary fiction is so powerful that it draws in readers even if there is no conventional hook.

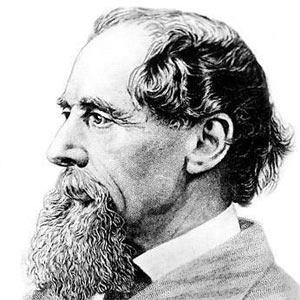

I’d also like to point out that while the distinction between commercial and literary only seems to have become sharp in the past century or so, there are revered writers of the past who took a more commercial approach, like Dickens, Austen, Twain, and Shakespeare, in addition to the many whose works were more literary, like Dostoevsky, Hugo, Hemingway, and Woolf.

As to writers, in terms of the choice of which to write, I could take up questions of markets, pay rates, respect, and the like, but I’ll ditch that in favor of this question: what do you love to read? If your idea of a good afternoon reading involves something like Les Miserables or The Druggist of Auschwitz, then you probably won’t be satisfied writing romance or fantasy, even if you think that’s all you could write that would sell. My guess is that contrarily, if you reach for books by Lawrence Block or Stephen King or Stephanie Meyer, then forcing yourself to write literary fiction will likely be a joyless and doomed exercise.

Of course, if you read both, you have your pick, or you can go back and forth, or you can shoot for books that are written as genre but sometimes sold as literary, like The Time Traveler’s Wife or Outlander or The Lovely Bones. If you feel comfortable in either world, then it’s probably time for you to consider what kind of career would be most enjoyable for you, picturing yourself at the height of success and working backwards–which is probably a good exercise for anyone, writer or not.

Bookshelf photo by chotda

Like this:

Like Loading...