Self-motivation and willpower can benefit from learning a lot of different skills: setting goals, tracking progress, repairing broken ideas, organizing priorities; exercising and eating well and trying to get plenty of sleep and meditating to have energy and support a good mood; making rules … and while it’s possible to have willpower without using every one of these tools, the more of them we use effectively, the stronger our willpower is.

Self-motivation and willpower can benefit from learning a lot of different skills: setting goals, tracking progress, repairing broken ideas, organizing priorities; exercising and eating well and trying to get plenty of sleep and meditating to have energy and support a good mood; making rules … and while it’s possible to have willpower without using every one of these tools, the more of them we use effectively, the stronger our willpower is.

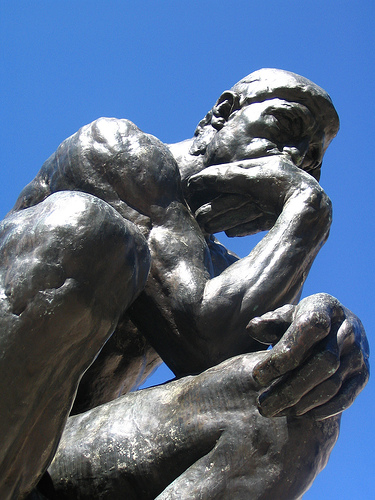

One key theme

And yet there’s one simple principle that underlies almost all of these tactics. It’s much easier to state than to follow, but thinking about it helps us keep focused on what willpower means and on what we can do from moment to moment. It goes like this: Think more about the right things and less about the wrong things.

What I mean is that for any goal I might have (for instance, let’s say I was someone who did project proposals as part of my job and wanted to finish three new project proposals by the end of the week), there will be thoughts I could have that will help make that happen (like “there’s a good chance the higher-ups will be pretty impressed if I can pull this off” or “the next step would be doing that competitive analysis”), thoughts that I could have that will get in the way (like “I couldn’t get my proposals done on time the last time, so I’ll probably screw up again this time” or “I hate this work. I just want to go home and eat Twinkies”), and thoughts that won’t have any impact one way or the other as long as they don’t distract me too much (like “These shoes are getting pretty worn out” or “Wow, there’s an albatross outside my window!”). These are right thoughts, wrong thoughts, and neutral thoughts, respectively. The neutral ones we don’t care about, so that’s the last I’ll say of those.

By the way, I want to be clear that I don’t mean that the “right” thoughts are “right” because they are somehow morally better than the “wrong” thoughts. We’re just talking about right or wrong for moving toward a particular goal.

The direct approach

People often seem to talk about thoughts as though we have no control over them, as though they just arise in our heads, stay as long as they want, and then leave without any permission or control on our part. Fortunately, this isn’t the case. We can actively choose to think more of the right thoughts and less of the wrong thoughts by reflecting on our own thinking (a process called “metacognition,” which is one facet of mindfulness) and by focusing our attention.

For instance, if I’m trying to play less golf in order to spend more time with my family, and if I then find myself thinking about golf, I can consciously 1) recognize this and 2) select something different to focus my attention on. So when the thought comes into my head “This weather is perfect for golf,” I can then ask myself “Would it be perfect for doing something with my kids, too? What would be fun that we haven’t done in a while?” The more I think about that second, right thought, the less attention I’ll have to spare for that first, wrong thought.

Violence doesn’t solve anything

It’s useful to recognize that “right” thoughts aren’t just negations of “wrong” thoughts. The problem with trying to argue myself out of a “wrong” thought is that the more I mentally struggle with the problem, the more attention I’m giving it, and so the more opportunity the behavior I don’t want has to ensnare me. If I let that thought go and instead focus on letting something else appeal to me, then I can be led away peacefully rather than trying to defeat my own desires in mortal combat.

What tools are good for

With all of that said, thinking more of the right thoughts and less of the wrong thoughts isn’t always easy, and it’s not always clear how to do it. Nor is it always easy to focus our attention on our own thinking enough to recognize when we’re getting drawn into non-constructive thinking. To make things easier, we come full circle to the kinds of skills I mentioned at the beginning of this post, skills for making ourselves more resilient, understanding ourselves better, redirecting ourselves more easily, and so on. Feedback loops, rules, tracking, idea repair, and all the other mental tools I talk about on this site help support the process of thinking more of the right thoughts and less of the wrong ones. Regardless of what tools we use, taking charge of our own thoughts leads in the direction of achieving what we want to achieve.

Thinker photo by Rob Inh00d

Albatross photo by MrClean1982

In previous articles, I gave a

In previous articles, I gave a