I’ve aspired for years to keep my inbox empty and up-to-date, but it wasn’t until very recently that I figured out how to actually achieve it. Before, my idea was “Well, I’ll kind of reply to things in order of importance and just try to really keep on top of it.” This is another way of saying “I’ll just try harder,” and just trying harder doesn’t work . While I was aware of this on some level, I didn’t see a better solution available for the time being, which is fine–we can’t tackle every goal in our lives all at once. But then I learned how to actually get it done–and it turned out to be quick and even kind of fun.

Why keep an empty inbox?

Keeping an empty inbox means no worrying that there’s something I ought to have replied to, no forgetting to follow up on important matters, no burdened sigh on seeing a long list of maybe-I-need-to-do-something-about-some-of-these messages every time I open my e-mail. It improves my mood and keeps me focused on things I actually need to do.

I’ve only had an empty in-box for a short time, but all indications so far are that it will be much easier to keep an empty inbox now than it was to keep a full one before. What enabled me to really tackle this job was switching to a Web e-mail client that I could access from everywhere instead of using one e-mail client on my laptop and another at home on my desktop. Using two programs meant I had to process every single e-mail twice, which was tedious and didn’t seem worth my time. Using the Web client gets rid of this problem, though it doesn’t in and of itself provide any solution to inbox management.

The setup

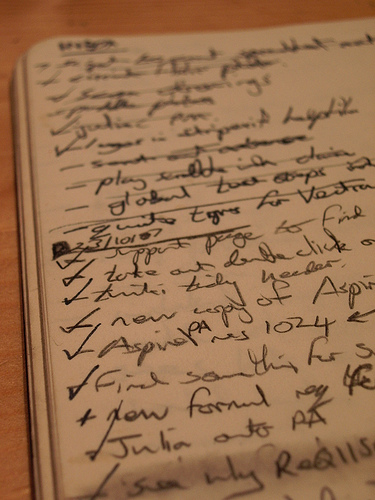

So Web mail for me was what opened the door to keeping my inbox empty. But what am I doing differently to actually accomplish it? Well, let’s take a look at my e-mail folders (see the close-up, below). The key to this system is that group called _Utility. All the other folders are just where I keep old e-mail for reference.

“Information” contains e-mails that have something in them I might someday need to know: login information for a new hosting account, a discount code for a Web site I shop at sometimes, a schedule for a conference I might go to, that kind of thing. It’s there only to keep the most important reference information I receive through e-mail all in one place. Because of the small number of things I need to keep here (I only use it for information I have a high probability of needing), it’s always easy to find what I’m looking for. I’ve been using this strategy for years, and it’s worked really well for me.

“Information” contains e-mails that have something in them I might someday need to know: login information for a new hosting account, a discount code for a Web site I shop at sometimes, a schedule for a conference I might go to, that kind of thing. It’s there only to keep the most important reference information I receive through e-mail all in one place. Because of the small number of things I need to keep here (I only use it for information I have a high probability of needing), it’s always easy to find what I’m looking for. I’ve been using this strategy for years, and it’s worked really well for me.

“Pending” contains e-mails about things I’m expecting from other people. I review it regularly to see if there are any situations that have changed or gone on too long and require my attention. Because there are usually only a few e-mails I’m waiting to have someone else follow up on, it usually contains very few items. Right now it holds only one, a note from someone who owes me a refund on a defective computer part. This is a new category for me in e-mail, but a similar category has worked really well for me in my task list (I use ToDoist, which is free unless you want a few extra geegaws, has good features, and is very easy to use.)

“REPLY or act” is my folder for e-mails that need a substantial response or that require me to do something. This might seem like just another inbox at first glance, but it’s actually the key to the whole system. E-mails only go into “REPLY or act” if I have

1) already looked at them, and

2) need to take some action (writing back or doing something), and

3) have decided exactly what kind of action or response I need to provide, and

4) have decided I’ll definitely take that action or make that response (that is, there are no “maybe follow up on this” e-mails in this folder), and

4) can’t answer the message in two minutes or less.

Before I started this system, my inbox contained thousands of e-mails. As of this moment, my “REPLY or act” folder contains exactly eight, none more than a week old.

“Things to Read” is where I put things that I’m interested in reading but don’t need to specifically get back to anyone on or do something about–blogs of interest, a non-critical update about a group I’m involved in, etc. I only put things in here if they will take some time to read: anything that I can read within a few minutes gets read right away and never makes it to this folder.

How it all fits together

What this means is that going through my inbox ends up being a process of making quick decisions and taking quick actions. Here’s a letter from a friend: I’ll put that in “REPLY or act” and respond at length later on. Here’s a long description about new features on that Web site I use: I’ll put it into “Things to Read.” Here’s some spam and a couple of notices I’m not interested in: delete, delete, delete. Here’s a short e-mail about recent events at my son’s school: I’ll read it now and then file it. Here’s an e-mail asking if I’ll be at Taekwondo class Thursday: I’ll fire off an answer now. And so on.

The result is that I can mow through everything in my inbox in a very short period of time and bring it back to “empty.” Anything that takes a long time by definition gets shuffled into one of the utility folders.

Then whenever I go into e-mail and don’t have anything in my inbox, or else get through the inbox quickly and don’t find anything interesting, if I actually have some time, I dive into my “REPLY or act” folder, open the oldest e-mail in it, and reply to or act on it. I had tried using a “reply or act folder” with my old system, but since I hadn’t figured out yet how to keep my inbox clear, the huge mass of e-mails in the inbox always distracted me from looking at “reply or act.” With the new system, my empty inbox forces me to look into my utility folders if I want to do anything. What I’m finding is that instead of feeling paralyzed by the mass of mostly low-importance, undealt-with e-mails in my inbox, I’m energized by the short list of really meaningful e-mails in “REPLY or act.”

Principles for easy e-mail management

It’s important to point out that I process everything in my inbox only once. If some message really is going to take a prolonged decision process, it can go into “REPLY or act,” but usually the decisions take a very short period of time. In the past I would defer them in favor of digging around for a more interesting piece of e-mail. Now I have a rule that if the decision is short I make it immediately, and this allows me to respond very quickly to all kinds of e-mails that otherwise might have languished for weeks.

So, the three principles that need to be followed for this kind of system to work are:

1. Process everything in the inbox from beginning to end regularly

2. Don’t defer dealing with e-mails that just need a quick decision or read or a short response

3. Review actionable e-mails in utility folders on a regular basis.

One exception to the above: if you know you have time to answer a more lengthy e-mail, you can just process your other in-box items and then get back to the e-mail you want to answer right away. Anything you are going to act on immediately after processing your inbox never needs to go into the utility folders at all. Just whatever you do, don’t leave something in your inbox because you want to follow up on it soon but can’t immediately. Even one leftover e-mail can encourage us to avoid inbox processing, and all that needs to be done is to put that e-mail into the Reply folder, maybe with a star or a red flag if it’s of special interest.

How to get started

To set this kind of system up, what do you do with the half-a-billion e-mails already in your inbox (if you’re like me and had them piling up)? Well, you need to set aside some time if you’re going to do this, but it only took me a little more than an hour to set mine up and get organized. Once you have your block of time, here’s the process I’d suggest:

1. Make a set of utility folders that works for you.

2. Pick a time period, from 5-30 days. Anything this recent, you’ll consider “fresh” e-mail. (Don’t worry: older e-mails will be covered in a later step, so this doesn’t have to be a long period. I used 10 days.)

3. Move everything older than that to a new folder called “Old Inbox.”

4. Process your inbox in the way I’ve described, starting with the first item and going through all e-mails without skipping any. Only process! This means: delete e-mails you don’t need, put messages needing long responses in your reply folder, file away non-actionable e-mails you want to keep, and deal immediately with any e-mail that you can get through in two minutes or less. Don’t get bogged down in detailed responses for anything that isn’t absolutely urgent: only answer e-mails that will take 2 minutes or less for now. Even very important things, as long as they don’t need to be done right this second, shouldn’t merit responses: you’ll have a chance to get to those soon.

5. When you have processed all of your fresh e-mail, you will have an empty inbox. Everything has been deleted, queued in a reply/act folder, queued for reading, stored with pending (waiting for someone else) items, or filed away.

6. If you think there may be anything important in your Old Inbox folder, start going through it from the most recent item going back. Just skim the titles and check e-mails as necessary if you need to know what’s in them. Don’t worry about processing everything in here unless you have a lot of extra time: just look for actionable items and put them in reply/act, to read, or pending. Everything else is just reference and can be found within Old Inbox if you ever need it. (This step will be especially easy if you’ve been flagging important e-mails prior to now: start by processing all of your flagged e-mails.)

7. Keep your inbox empty by following the three principles above.

My categories are just guidelines: you may find a different way you prefer to sort your e-mail. However, you may find something very similar is the most efficient method for you if you’re interested in keeping a clean inbox. However you organize, make very clear distinctions between actionable e-mail folders and non-actionable ones, or you’ll start to get a huge mass of stuff accumulating without knowing off the top of your head what needs your attention and what doesn’t.

This post owes much to the ideas of Dave Allen and to his book Getting Things Done, although it also is informed by personal experience and organizational skills I’ve learned over the years. Here’s hoping you find it useful.

Like this:

Like Loading...