In two recent posts (“Why Amazon Studios Will Succeed, Part 1: Crowdsourced Projects” and “Why Amazon Studios Will Succeed, Part 2: Customers and Distribution“), I’ve talked about the advantages Amazon has in becoming a producer and distributor of movies and series. That’s clearly great for Amazon, and it seems likely it will be great for audiences, too.

How will Amazon Studios affect writers?

What I don’t know at this point is how writers will be affected. My guess is that it will be much like the Kindle Store: some writers will come up with products that catch on and will do spectacularly well while most won’t see any significant success at all. Disappointing as that is for the majority of would-be screenwriters, that’s as it should be: there’s only so much media the world needs, and not everyone who wants to be a screenwriter can be: those who are most persistent, passionate, and hardworking and who make the most effective project choices will succeed.

For better or for worse, I suspect Amazon Studios will begin to suck some of the profit out of the traditional movie and series production channels, which is likely to limit opportunities for writers there. The game changes, and players just shift around. Overall, our hunger for new content is likely to be about the same either way, and I don’t see Amazon changing the total number of successful screenwriters very much, unless they’re successful in getting a lot of niches interested in a lot of niche projects, in which case there will be more jobs for less pay.

However, there’s an argument–one I’m inclined toward, but not ready to back wholeheartedly–that an Amazon Studios system will be better for writers than the traditional routes to screenwriting success. Why? Because instead of a small number of gatekeepers who are sometimes difficult to access, gatekeeping duties instead get assigned to the Crowd. This means that if a story can capture people’s interest, it’s likely to succeed–the successes would be less subject to individual whim, preference, and assumptions of what does and doesn’t work.

On the other hand, a reasonable person could say that this is likely to result in more pandering to the masses, more success of whatever stories take the cheapest and easiest routes to popularity. If a reasonable person were to say this to me, however, I would laugh in that reasonable person’s face. After all, look at movies and television programs now: for every truly innovative or meaningful project, there are a hundred others that are cheap, derivative, or even detrimental to our experience as human beings. It seems likely to me that quirky, meaningful projects that really do have meaning for a lot of people are more likely to succeed in a crowdkeeping environment than in a gatekeeping environment, because the best thing gatekeepers have to go on is past successes, whereas a crowd can give a reliable response directly from the gut.

Then again, the Kindle Store successes to date have tended to be the same mysteries, thrillers, and paranormal romances that crowd the bestseller racks everywhere, so what do I know? Maybe I shouldn’t be so optimistic on that count. In my defense, I did say I’m not ready to fully back that view at this point.

My experience with Amazon Studios

In my case, I have a feature-length film screenplay called Down based on my Writers of the Future winning novelette “Bottomless.” The script has been out to quite a number of agents, managers, production companies, and contests, but apart from a few mildly encouraging comments has gotten nowhere. For a number of months, it has basically been doing little else than taking up space on my hard drive.

This is a story that I love. It takes place in a vast bottomless pit, lit by a sun-like thread down the center, and populated by villages built on ledges all around its walls. The cardinal rule in this world is that you don’t throw anything into the Pit, because if you do, it’s likely to kill someone somewhere below you. It’s basically an entire world built on fear of heights and vertigo. I really enjoyed writing the story and enjoyed even more expanding it into a feature-length film, in which a young man obsessed with the secrets of the Pit (Why is it there? Is there a bottom or not?) is exiled from his village and journeys deep, deep into Pit in a search for answers–and when he finds them, he discovers a danger much worse than anything he had imagined.

I’ve uploaded Down to Amazon Studios: you can see it here, and even download the screenplay if you like. It has done well so far in Premise Wars, a game anyone can play on Amazon Studios’ home page (just go to http://studios.amazon.com and scroll down to the gold Premise Wars heading), where you’re presented with two brief descriptions of movie projects and you select the one you like better. The top 10 Premise Wars projects as of this writing have won in the range of 53%-71% of the time, while Down currently has won 77% of its Premise Wars battles–but Amazon determines the Premise Wars winners on a secret formula that, as they describe it, makes complex adjustments based on which other premises any given premise has bested. This more or less explains how premises that have lost more than they have won in Premise Wars are still making the leaderboard (though not, at the moment, in the top 10 spots), even though it’s a little hard to believe that they’re doing so much better with an adjusted score than they do with their raw percentage. However, my impression is that being in the top 10 on the leaderboard doesn’t necessarily count for much anyway: it seems to matter much more if people review your script positively or decide to make a trailer for it. We’ll have to see if either of those things develop down the line.

My next post in this series will cover some of the dangers and limitations writers face at Amazon Studios.

Movie shoot photo by jonas maaloe

Down image by writer Elise Tobler.

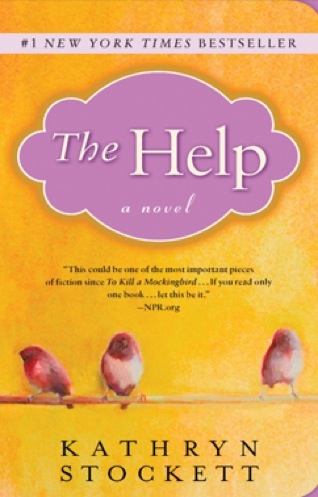

Kathryn Stockett, author of The Help, has become my new favorite example of the power of persistence. She certainly hasn’t made me forget about Jo Rowling, whose first Harry Potter book was rejected by 12 publishers before finding a home at Bloomsbury, but Rowling got representation from the second agent she tried, while Stockett reportedly got at least 45 rejections for The Help before even finding an agent (see

Kathryn Stockett, author of The Help, has become my new favorite example of the power of persistence. She certainly hasn’t made me forget about Jo Rowling, whose first Harry Potter book was rejected by 12 publishers before finding a home at Bloomsbury, but Rowling got representation from the second agent she tried, while Stockett reportedly got at least 45 rejections for The Help before even finding an agent (see