Attending Readercon recently, I was struck by discussions I heard and took part in that brought up the problem of inclusivity and exclusivity in fiction: that is, what kinds of characters are conspicuously not present or very often stereotyped. This applies to race, but also to a lot of other categories: sexual preference, gender and gender identity, age, disability, mental health, social and economic class, and others.

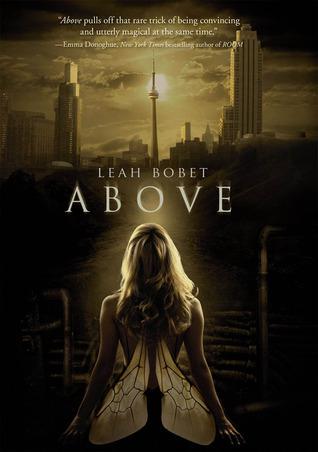

The question I’m left with as a writer is this: what am I not doing and not seeing that’s contributing to the problem, and what can I do and understand that will contribute to making things better? So I’m doing a series of interviews with writers I admire who have things to say on the subject, starting with this one with Leah Bobet, whose novel Above (Arthur A. Levine, just out in April) tackles physical differences and marginalization in a novel and compelling way. Publisher’s Weekly gave it starred review: “Bobet effortlessly blends reality and fantasy, her characters are both gifted and broken—hers is a world that is simultaneously fantastic and painfully real.”

LUC: A lot of your fiction deals with characters that aren’t common in the books and stories we often see. From your point of view, is this tendency of most commercial fiction to prefer white, fairly young, straight, “non-ethnic”, monotheistic, neurotypical, non-disabled, and otherwise “normal” (perhaps I should say “as-though-normal”) characters a problem, or are you just taking a different path? If it’s a problem, what’s wrong with it?

LUC: A lot of your fiction deals with characters that aren’t common in the books and stories we often see. From your point of view, is this tendency of most commercial fiction to prefer white, fairly young, straight, “non-ethnic”, monotheistic, neurotypical, non-disabled, and otherwise “normal” (perhaps I should say “as-though-normal”) characters a problem, or are you just taking a different path? If it’s a problem, what’s wrong with it?

LEAH: Hah – you’re asking me if this is a creative decision or a political one! Well-played. And, well, it’s both. They’re inextricable.

I feel that it’s definitely a problem, yes – and it’s because of that word “normal”. We’re none of us normal, and we’re all normal, and that’s not just the thing your parents tell you to make you feel better when some bigger kid pushed you around for whatever invented reason. Calling one (fairly narrow!) kind of person “normal” makes people expect that their stories are the most important, and ultimately, that anyone who falls outside those lines doesn’t really have stories. And they do. We do. You do.

Not only does that rob everyone of a whole lot of interesting stories, but it slowly and concretely gives us the idea that those people who aren’t “normal” don’t really matter. They don’t have stories, so they don’t do interesting things; fight fights; reconcile; cry; learn; fail. They don’t exist.

And telling most of the people in your society that they subtly don’t exist? Just, well. Seems like a bad idea to me.

LUC: So what happens when traditionally disregarded groups of people do make it into our novels and stories, especially as central characters? What kinds of impact can or do we have on readers when we write more inclusively?

LEAH: Well…just like with any work of fiction, a few things can happen. It depends on who’s writing the work – are they in the group, or out of it? – and who’s reading it, and how well the portrayal is done.

The portrayal can be done sloppily or on the basis of the kind of harmful stereotypes that most people have about someone else without even realizing it, and then people are hurt and angry, and there are negative feelings all around. Or, when it’s done thoughtfully, it can still sink like a stone: Books or stories fail to catch on all the time, for reasons I’m sure most of publishing would pay in body parts to figure out. Or, well, there can be a benefit to readers, or to the community overall.

I think it’s probably hard to say where those social benefits begin and end. Readers are people, and each person has a different and individual relationship with the various labels and roles that make up their identity (and that’s the first trap of all: thinking that just because someone is a member of a minority group, that that identity is their identity, or that all members of a given group have the same relationship to that part of their lives. It’s not, and they don’t.) So one reader might see themself in a character and feel like their existence, their stories, are being acknowledged by the larger community. Another might start thinking about how their neighbour sees the world, and even if that’s not how their neighbour sees the world at all, learning to be considerate is, I think, a real plus. Another might say, “That’s not what being X is like,” and then be clearer on what, for them, being X is actually like and why someone else might see it that way, whether that someone else is a member of the group or not.

Someone else might realize, in the back of their head, that there are more stories and ways of living out there than their own, and develop further the kind of open-mindedness that makes you not automatically reject someone living differently than yourself.

This happens. This works. Once upon a time when I was eleven years old, and didn’t even have much of a concept of gay people (yeah, it was a pretty isolated and homogenous suburb, and it was the early nineties. I know.) I read Poppy Z. Brite’s Drawing Blood. Besides all the vampire sex and killing, what I took from that was that gay people are just people with relationships and problems and to do lists and lives to run and stories. And although here and there I’ve struggled with the kind of ingrained prejudices you get when you grow up in a largely racially homogenous, economically homogenous, religiously homogenous isolated suburb, that has never been one of them. Right story, right time, right reader.

So I guess what I’ve been groping towards here is that portraying characters and people who aren’t in that narrow band of traditional North American “normal” can, at its best, make people different from a reader not other. It can make a reader go, “Oh, right, that person is still a person,” instead of seeing a role, a stereotype, an other. It can make all the readers out there who don’t fit in that narrow slice of the population whose stories are always told – being, most of the population of North America right now – feel like yes, everyone else sees them; they are acknowledged as part of the community too. That they have a voice and a place, and space to be more than the stereotypes that are frequently expected. It gets writers who aren’t part of that narrow slice of the population out there, heard, and paid, which is really important, because having homogenous professions in a heterogenous community can be really toxic when it comes to things like public policy, and who needs what, and how it needs to be done in the everyday world.

And then? Maybe we all treat each other better.

I’ll have more questions for Leah in a follow-up interview down the road.

Leah Bobet is the author of Above, a young adult urban fantasy novel (Arthur A. Levine/Scholastic, 2012), and an urbanist, linguist, bookseller, and activist. She is the editor and publisher of Ideomancer Speculative Fiction, a resident editor at the Online Writing Workshop for Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror, and a contributor to speculative web serial Shadow Unit.

She is also the author of a wide range of short fiction, which has been reprinted in several Year’s Best anthologies. Her poetry has been nominated for the Rhysling and Pushcart Prizes, and she is the recipient of the 2003 Lydia Langstaff Memorial Prize. Between all that she knits, collects fabulous hats, and contributes in the fields of food security and urban agriculture. Anything else she’s not plausibly denying can be found at leahbobet.com.

Like this:

Like Loading...